IDA TARBELL -- THE WOMAN WHO TOOK ON ROCKEFELLER

CLEVELAND — OCTOBER 1903 — The small church hushed when the billionaire appeared in the doorway. Heads turned. Whispers — “that’s him!” Watching from a rear pew, a journalist took notes. “There was an awful age in his face. The oldest man I had ever seen, I thought, but what power!”

For two hours, the journalist watched the billionaire. He shifted in his seat, eyes darting, looking over his shoulder. He seemed consumed by “a terrible restlessness.” Threats, suspicion, and “hunger for notoriety, blackmail, revenge” had turned this rich, cunning man into “one of the saddest objects in the world.”

Few battles have been so mismatched. On one side stood the legendary tycoon, master of a monopoly that controlled 90 percent of American oil. And on the other side stood a small woman with a pen and a driving need to learn how John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil became so vastly wealthy and so thoroughly corrupt.

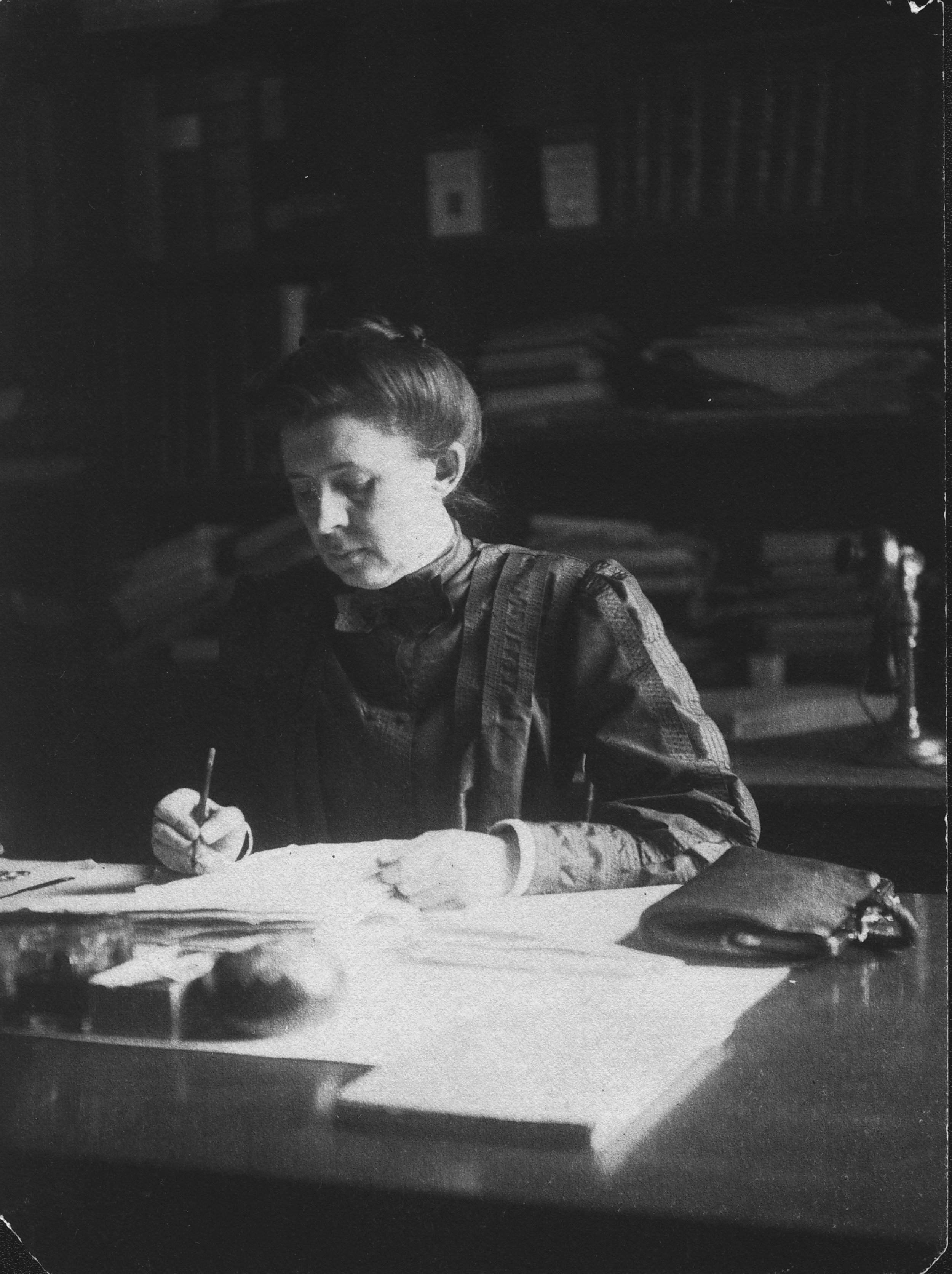

Ida Tarbell had no background in business. Trained in biology, she worked briefly as a schoolteacher, then began writing for magazines. Moving to Paris in 1891, she sent back features to McClure’s Syndicate. “The girl can write,” Samuel McClure told a colleague. “We need to get her to do some work for our magazine.”

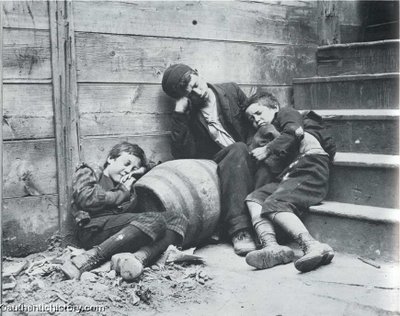

After three years in Paris, Tarbell came home to an America reeling from rampant industrialization. Mansions and millionaires. Tenements and homelessness. But wasn’t this how species evolved? By letting the weak die out? “The man in the gutter is right where he belongs,” one Social Darwinist said.

Ida Tarbell cared little for social policy. Getting rich was fine, if you played fair. Had America’s top-hatted tycoons played fair?

Deciding to investigate a trust, Tarbell considered steel, sugar, finance. Then she told McClure’s editors of her childhood in Pennsylvania, where the burgeoning oil industry had opened “a rich field for tricksters, swindlers, exploiters of vice in every known form.” Her father ran Tarbell Oil Tanks, making a good living. Then in 1870, an Ohio firm moved in.

Suddenly her father no longer smiled or sang. Tarbell recalled the night he “came home with a grim look on his face and told how he with scores of other producers had signed a pledge not to sell to the Cleveland ogre.” When Tarbell focused on Standard Oil, she was warned — “They will get you in the end.” “Don't do it, Ida,” her father said. “They will ruin the magazine.” But having seen the face of corporate greed, “there was born in me a hatred of privilege.”

“No industry in its early days has ever been more destructive of beauty, order, and decency than the production of petroleum. ”

For the next year, she pored over account balances, depositions, Congressional reports. “The charges continued to multiply,” she recalled. The Cleveland firm that crushed her father’s business had formed a monopoly, buying up railroads, refineries, oil tanks. But the Congressional report? Seems someone had bought up all the copies — except the one Tarbell found deep in the stacks of the New York Public Library.

When Mark Twain introduced Tarbell to a friend, the Number Three man at Standard, Tarbell spent hours talking with Henry Rogers. Why, she finally asked. Why not play fair? “Ah, but there was always somebody without scruples in competition,” Rogers said, “however small that somebody might be. He might grow.” And there it was, Tarbell saw, “the obsession of the Standard Oil Company. . . that nothing, however trivial, must live outside of its control.”

Tarbell also talked to Rockefeller’s Number Two. Henry Flagler said of the old man, “He would do me out of a dollar today.” On she persisted, turning over rocks, finding cuthroat contracts, corners cut, laws stretched or broken.

Tarbell’s series began in McClure’s in November 1902. For 18 months, the story unfolded. “An Unholy Alliance,” “Cutting to Kil,” “The Standard Oil Company and Politics.” McClure’s circulation doubled. In 1905, The History of the Standard Oil Company became a book — two volumes — an instant best-seller.

Rockefeller said nothing. Privately he denounced “Miss Tarbarrel,” but told his associates, “Not a word. Not a word about that misguided woman.”

Finished, Tarbell hoped to write biographies like those she had written about Lincoln and Napoleon. But from across America, people sent word of Standard’s continuing corruption. She went on to write more exposes and a scathing character study of Rockefeller.

In May 1911, the Supreme Court broke Standard Oil into 34 separate companies — Standard Oil of New York (Mobil), Standard Oil of New Jersey (Exxon), Standard Oil of California (Chevron) etc. Two years later, The Federal Trade Commission was formed, followed by the Clayton Anti-Trust Act.

The woman with the pen, having no background in business, had penned what one historian called, “the single most influential book on business ever published in the United States.” And in closing her 800-page history, Ida Tarbell left America with advice about corporate corruption.

“As for the ethical side, there is no cure but in an unceasing scorn of unfair play — an increasing sense that a thing won by breaking the rules of the game is not worth the winning.”