"ICARUS" -- THE PHOTO THAT FLEW

MANHATTAN — 1927 — On streets far below, as the president said, “the business of America is business.” And high above the city the “race to the sky” began. 40 Wall Street reached 927 feet. The Chrysler Building soon topped that. Then in the spring of 1930, in Manhattan’s Midtown, men began climbing, building, soaring higher than in all of human history.

Skyscrapers had been photographed for decades, but always from the ground. Then one photographer had the vision and the courage to shoot from the top.

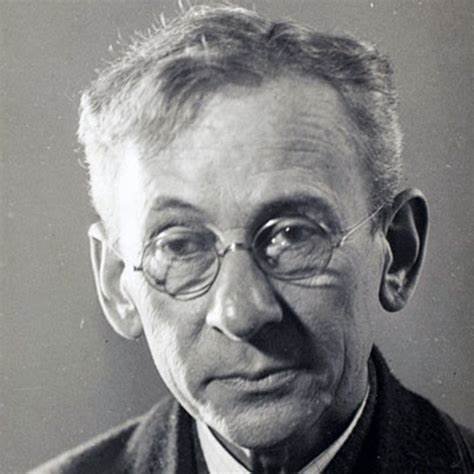

In front of the camera, Lewis Hine was a shy, bookish man, but behind the lens he was as driven as any artist, as dedicated as any reformer. “Cities do not build themselves,” he said. “Machines cannot make machines, unless back of all of them are the brains and toil of men.” And so at age 56, Hine began scaling scaffolds and hanging from safety lines, nothing below him but “a sheer drop of nearly a quarter mile.”

Thousands of us have stood on the Empire State Building’s 86th floor deck. There the thought of stepping out sends ice water through us. Yet here (below) s Skyboy, as Louis Hine called him, flying above the city on a single strand of cable.

No one knows his name. Hine later called him Icarus after the Greek hero who fashioned feathered wings and flew. Hine’s photos of Icarus’ fellow laborers are identified only by their jobs. Plasterer, sheet metal worker, cement mason, bricklayer. . . Most were Irish or Italian immigrants. A few dozen were Mohawk ironworkers, famous for their indifference to heights. And all of them, Hine knew, were heroes.

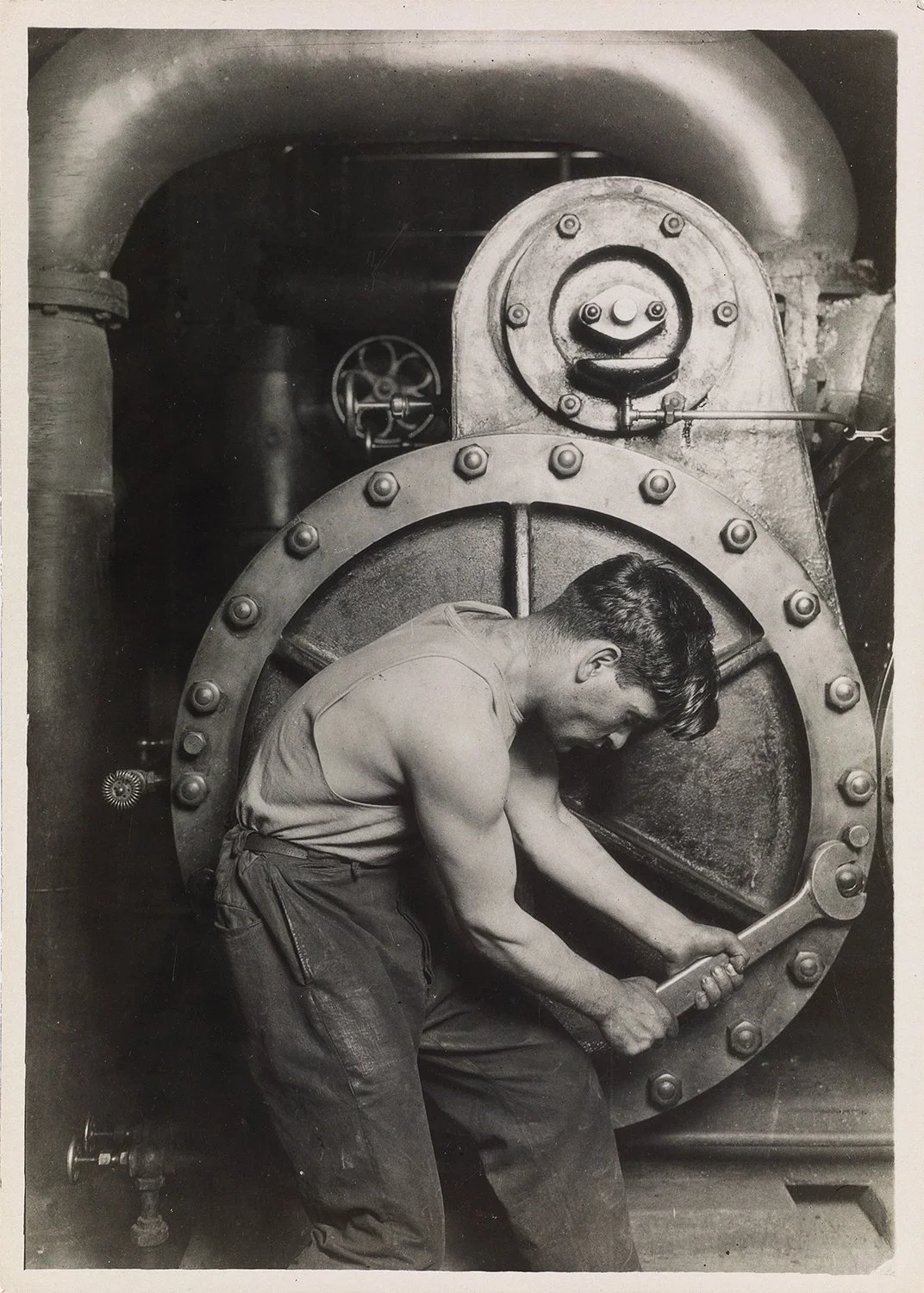

“I have brought some of them here to meet you,” Hine wrote in Men at Work. “I will take you into the heart of modern industry where machines and skyscrapers are being made, where the character of men is being put into the motors, the airplanes, the dynamos upon which the life and happiness of millions of us depend.”

Hine knew Labor from the ground up. When he was 18, his father died, sending Lewis to work in a furniture factory to support his mother and sisters. For the next decade, he toiled as a janitor, a wood cutter, a mailman. . . After going to night school, he finally became a teacher. Then in 1903, his principal needed a school photographer. Hine was soon toting a bulky camera, firing off flash powder, capturing light on glass negatives.

Unlike Alfred Stieglitz or Edward Steichen, Hine never considered himself an artist. His was “detective work.” Two million children were toiling in American mines and mills, but industrialists denied putting anyone under 14 to work. So Hine, hired by the National Child Labor Committee, posed as a Bible salesman, a business reporter, a fire inspector. And he caught images that indicted the nation.

Alarmed, Congress passed the first child labor law in 1916. The Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional. Hine kept shooting. Then in 1919, having “done my share of the “negative,” Hine shifted focus.

As the Twenties roared, Hine continued to roam America. His “work portraits” captured “men and women that go daily to their tasks in the great industrial structure.” Hine photographed hat makers, postal workers, cops, steel workers. By 1929, disappointed that his work had not earned much attention, he considered retiring. “Then came this Empire State job.”

Hine had to work fast. From first beam to finished spire, the world’s tallest building was erected in 13 months. Some 4,000 men, framing four or more floors per week, sent the building skyward. The bookish photographer was with them all the way, on scaffolding and in spirit.

“It isn’t really as dangerous as it looks,” workers told Hine. Others quipped, “it’s safer up here than it is down below.” Hine continued shooting, often from an open steel box hoisted by crane and dangled in the empty sky. In April 1931, when the Empire State Building was finished, he watched as workers hoisted an American flag 1,250 feet above Midtown.

“I have always avoided daredevil exploits and do not consider these experiences as going quite that far,” Hine wrote, “but they have given me a new zest.” The New Deal’s WPA soon sent him to photograph dams and power stations, but by then, other photographers were competing to honor the common American. Lewis Hine got less and less work

Hine died in 1940, nearly destitute. MoMA turned down his photos. It was only when the world of hard labor began to disappear people that saw what he had preserved — the dignity, the struggle, the honor of the people who built America. And in “Icarus,” he caught one such man, in one such moment, taking flight.