EDWARD S. CURTIS, SHADOW CATCHER

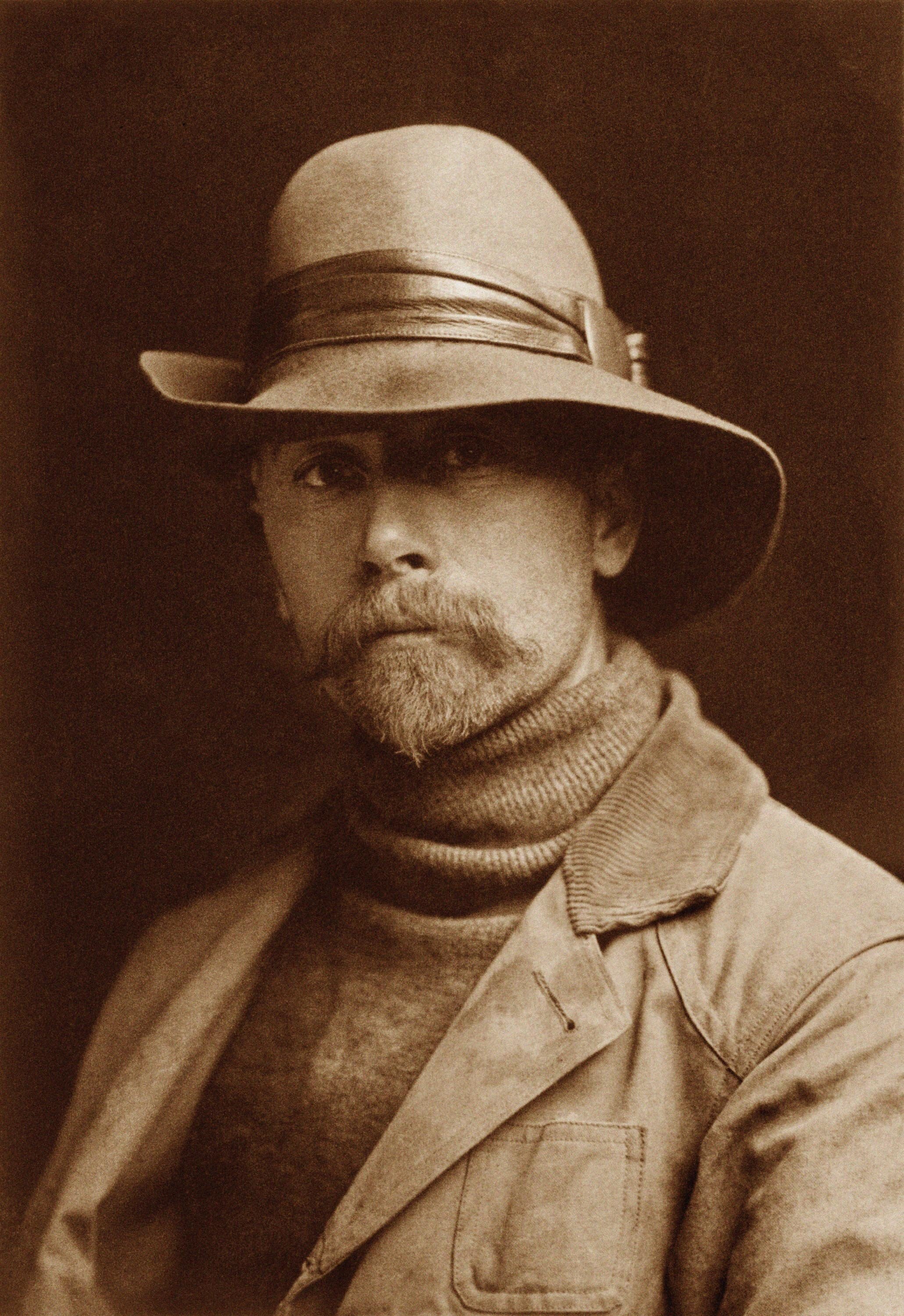

MORGAN LIBRARY, 1906 — The ragtag, goateed photographer sits before the richest man in the world. J.P. Morgan is skeptical. This man wants money, lots of it. He dreams of going among the Indians, who are rapidly vanishing from American life, and making a complete record of “their history, life and manners, ceremony, legends, and mythology.” Eighty tribes. Fifteen years of work, this dreamer says.

Morgan shakes his head, but then Edward Curtis opens his portfolio and magic emerges.

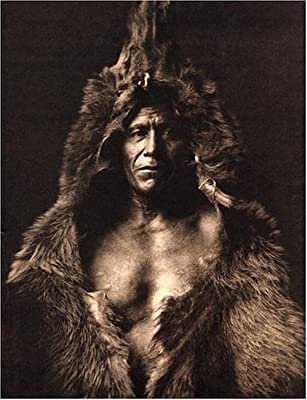

You’ve seen the images. Burnt sienna portraits of chiefs resplendent, young girls shadowed and mysterious. Sweeping plains and towering canyons where men on horseback seem sprouted from the landscape. You’ve see the images. You almost didn’t.

J.P. Morgan gave Curtis $75,000. In return, Morgan would receive 25 editions of Curtis’ project, The North American Indian, plus 500 prints. “My staff will take care of the financial arrangements,” Morgan said. Curtis walked out “in a daze,” and his ordeal began.

Edward Curtis grew up in the Midwest but left school after sixth grade. Fascinated by photography, he built his own camera. When his family moved to Seattle, Curtis apprenticed at a small studio. By 1890 he was the city’s most celebrated photographer, taking portraits of wealthy socialites. Then he turned his lens to a different subject.

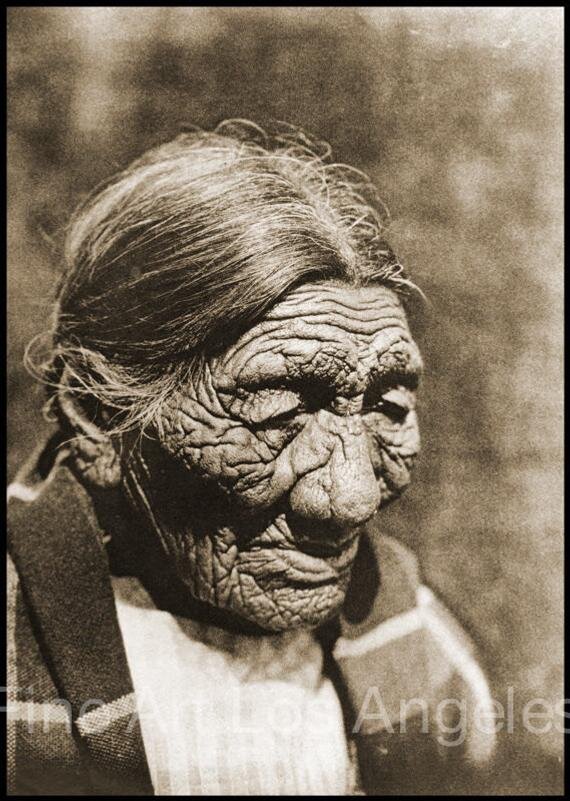

Princess Angeline, daughter of Chief Seattle, was reluctant, but Curtis talked her into posing. The photo caused a sensation, and Curtis soon posed Chief Joseph and other natives. When his photos caught the eye of anthropologists doing field work on the Plains, Curtis began tagging along. Roaming vast panoramas of teepees, grasslands, and mountains, he saw the past and his future.

But the past was endangered. “We are now working late in the afternoon of the last day,” Curtis wrote. “Each month some old patriarch dies and with him goes a store of knowledge."

Curtis was soon toting bulky cameras to the lands of the Hopi, the Navajo, the Kiowa. . . Setting up makeshift studios in teepees and tents, he befriended natives, earned their trust, and captured their shadows.

“The Shadow Catcher,” as natives called him, was never content with fine photos. He wanted to preserve “a vanishing race.” The Smithsonian thought the project too large. President Theodore Roosevelt, who summoned Curtis to take family portraits, recommended J.P. Morgan. “Little did I realize the full magnitude of the task I contemplated,” Curtis recalled.

Defying drastic weather, axle-busting roads, and Western distances, Curtis finished eight volumes before Morgan’s money ran out. Then life caught up with the shadow catcher. His wife divorced him, taking the house, the studio, and all his glass plates. His eldest daughter, not wanting Mother to profit from Father’s work, smashed the plates.

To raise funds, Curtis made a touring slide show and the first feature film of native life. But by 1915, Indians seemed like ancient history, and both projects lost bundles of money. To repay rising debt, Curtis moved to Hollywood and worked on silent films. Finally, in 1928, he resumed his life work, traveling with his daughters to California, then Alaska. At 60, he braved Arctic waters to visit the Nunivak people on their frozen island, then came home to finish his dream.

The North American Indian included 40,000 photos, 10,000 songs on wax cylinders, and 20 volumes of Curtis’ ethnography on native nations from Alaska to Texas. But when the last volume came out in 1930, no one cared. The Shadow Catcher died forgotten. We played Cowboys and Indians.

Then one day in 1972, a bookstore owner in Boston was rummaging in his basement. Opening one box, he dusted off a stack of amber photos. When the man dug deeper, the full story, like some black-and-white in a darkroom, slowly came to light.

Throughout the 1970s, Native-Americans were rising. As their populations grew and their stories were finally heard, the American Indian Movement reclaimed native customs and pride. The photos of Edward S. Curtis, shown in museums, galleries, and history books, were part of the renaissance.

In the years since, however, some natives have grown tired of these iconic images. So stereotypical, perhaps even staged. But Curtis, working in a nation that almost destroyed its natives, mocking and then banning their languages and customs, caught more than mere shadows.

“I hear people criticizing him,” said George Horse Capture of the Aaninin Gros Ventre, “but he did a monumental job. If he didn’t come along and record this, the loss would be tremendous. So when people start criticizing stereotypes, I look at his photo of my great-grandfather. He’s not a stereotype. You can’t stage that. You can’t stage the eyes and the determination. These were powerful people and he recorded them.”

Curtis captured a time and place that speaks to the soul. “When I first discovered Curtis,” a Piegan man recalled, “I saw this photo of three Piegan chiefs out on the Plains. I looked at this landscape and it felt so familiar, although I’d never seen it, except perhaps as a child. And it allowed me to go on my own journey. And I knew that deep down in my heart, I needed to come home.”