LYNN MARGULIS -- DEFYING DARWIN

A century after Charles Darwin rocked the world, the science was set in stone. Like it or not, we are descended from apes. Then in 1967 a single scientist disagreed. Set the clock back four billion years, she argued. Evolution began not with animals but with microbes.

Lynn Margulis’ revolutionary paper was rejected by 15 journals before being published in the Journal of Theoretical Biology. Hey, the journal seemed to say. You never know. But the scientific establishment knew, just knew.

“Your research is crap,” one reviewer wrote in rejecting one of Margulis’ grant proposals. “Do not bother to apply again.”

But Margulis also knew. Raising two sons while earning her doctorate, she knew how stubborn the male of the species could be. Despite relentless criticism, she knew her research was solid. And she knew the miracles of microbes better than anyone else on earth. She persisted.

“I greatly admire Lynn Margulis' sheer courage and stamina in sticking by the endosymbiosis theory, and carrying it through from being an unorthodoxy to an orthodoxy,” biologist Richard Dawkins said. “This is one of the great achievements of twentieth-century evolutionary biology.”

Like her first husband, astronomer Carl Sagan, Margulis was brilliant and charming, with gift for explaining difficult concepts to the rest of us. She came by these traits naturally. A precocious child, she entered the University of Chicago at 15, graduated at 19. Even before getting a Ph.D., she began teaching at Brandeis, and soon settled at Boston University where she dared to doubt Darwin.

“I woke up one morning and realized I am not a neo-Darwinist,” she recalled. Darwin and his disciples held that species evolve through mutation, genes randomly changing to give the taller giraffe, the longer-beaked bird an edge in the ruthless struggle for survival. Margulis proposed a kinder, cooler evolution based on “symbiosis,” microbes merging for mutual gain. Where Darwin saw “nature red in tooth and claw,” Margulis saw cooperation. “Life did not take over the globe by combat,” she wrote, “but by networking.”

On into the 1970s, Margulis stuck to her theory, earning a reputation as “Science’s Unruly Earth Mother.” Then, while raising two daughters from her second marriage, she again challenged science’s certainty.

“I noticed that all kinds of bacteria produced gases. Oxygen, hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, ammonia — more than thirty different gases are given off by the bacteria whose evolutionary history I was keen to reconstruct.” Perhaps, she thought, our entire atmosphere came from bacteria. No one believed her. “Go talk to Lovelock,” many said.

British biologist James Lovelock had an evolving conception of the planet. Mother Earth really is a mother, Lovelock said, an enclosed system as nurturing and connected as a single cell.

In 1974, as the environmental movement was greening, Margulis and Lovelock introduced their new conception of the earth: “The notion of the biosphere as an active adaptive control system able to maintain the Earth in homeostasis we are calling the 'Gaia hypothesis.'”

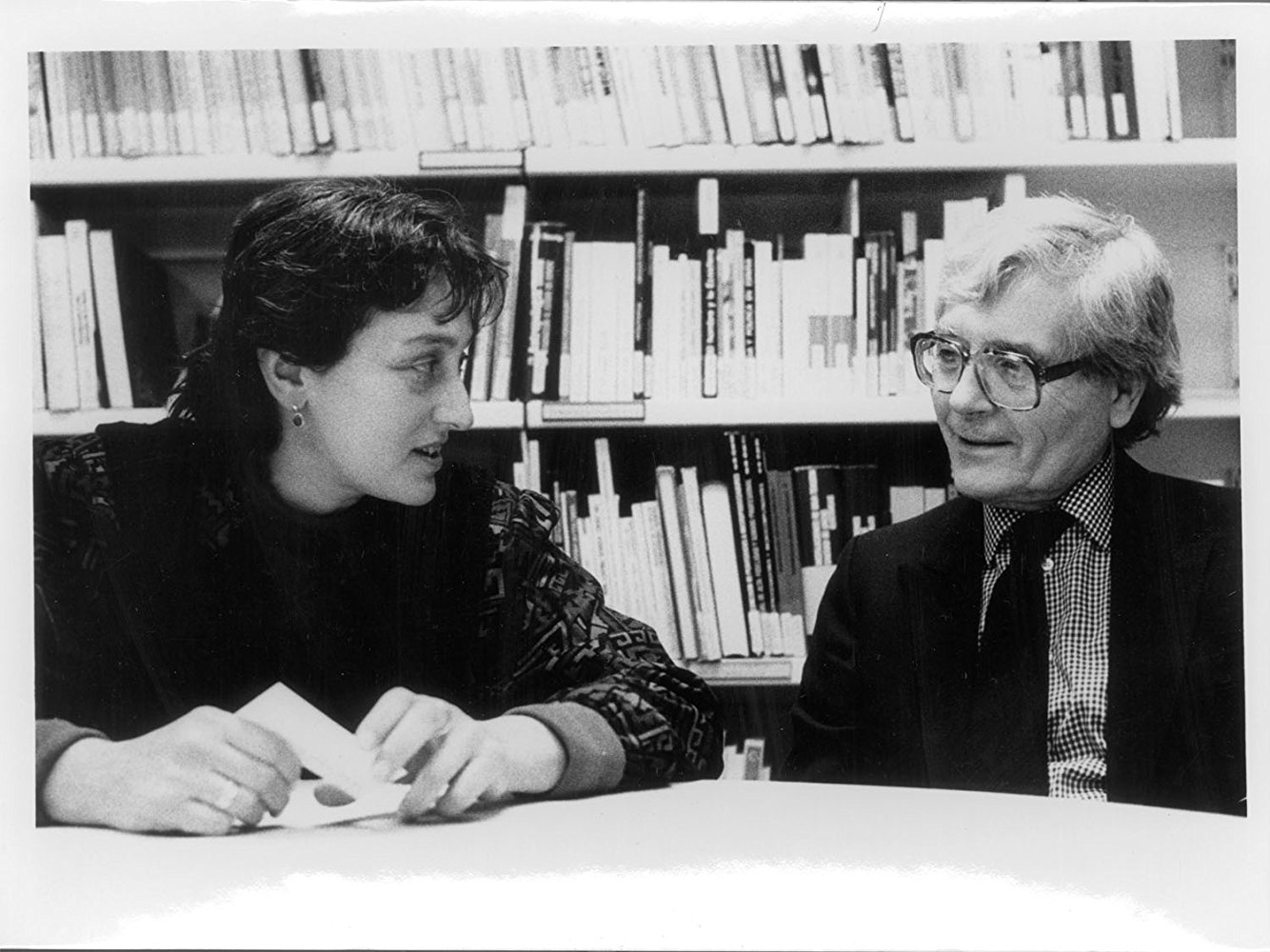

Gaia remains in dispute, but Margulis’ star was rising. In the 1980s, advanced genetics backed her symbiosis theory. “Crap research” prevailed and Margulis found a wide following. Awards, honors, and acclaim followed. Herself a symbiotic and social creature, she move to the University of Massachusetts, creating a lab where young researchers felt at home, hosting huge dinners where they shared ideas.

Margulis continued to advance new theories in micro-biology. She also co-wrote, with son Dorion, books bringing microbes to the masses. After Carl Sagan wrote Cosmos, Margulis and son wrote Microcosmos: Four Billion Years of Microbial Evolution. They followed with illustrated guides to microbes. A microbe coloring book. Even studies that explained sex for non-scientists.

“Science’s Unruly Earth Mother” remained controversial. Proven correct about symbosis and evolution, she proposed that bacteria itself changed in ways no one else believed. She even argued that 9/11 was an inside job. Margulis reveled in her role. “I don’t consider my ideas controversial,” she said. “I consider them right.”

Many who admired her persistence tired of her relentless roguishness, but others remain grateful for the woman who defied Darwin’s disciples.

“She was not shy about expressing her opinions,” John Brockman of Edge.com wrote when Margulis died in 2011. “Her in-your-face, take-no-prisoners stance was pugnacious and tenacious. She was impossible. She was wonderful.”