LINCOLN AND THE 'MOBOCRATIC SPIRIT'

ALTON, IL — 1837 — As darkness falls, as the river flows, hundreds of howling men, torches ablaze, surround a warehouse in this small town along the Mississippi. Inside sits their target — a printing press.

This is not Elijah Lovejoy’s first encounter with a mob. Three times his presses, guilty only of printing attacks on slavery, have been thrown into the Mississippi. Now another mob. . .

Someone puts a ladder up. A boy climbs it to set the warehouse roof on fire. Lovejoy emerges, topples the ladder, retreats. But when the ladder goes up again, he steps into the crossfire. The murder, says John Quincy Adams, ”is a shock as of an earthquake to this country.”

Weeks later, on a wintry Saturday evening, a tall, skinny man rises to speak before the Springfield Lyceum. The Lyceum has one rule for speakers — no politics. But mobs, the speaker knows, are the opposite of politics. His topic: “The Perpetuation of our Political Institutions.”

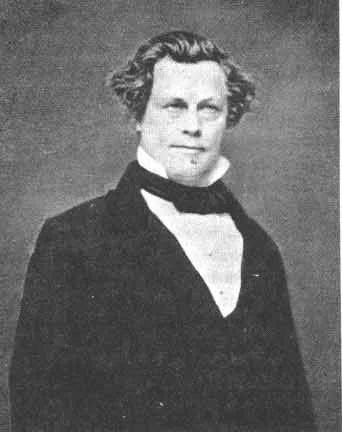

Few in the audience know him. A recent arrival in Springfield, he is a “prairie lawyer,” riding horseback to try cases throughout central Illinois. Awkward and ungainly, he also has, a friend says, “a gloomy and melancholy face,” a face etched with loss. At 28, he has already buried his mother and infant brother, his sister and his first love. His name is Lincoln. Now he begins.

“In the great journal of things happening under the sun, we, the American People. . . find ourselves in the peaceful possession of the fairest portion of the earth.” We did not earn this blessing, Lincoln continues. Our democracy is an inheritance, and our task is its preservation.

“How then shall we perform it? At what point shall we expect the approach of danger? By what means shall we fortify against it? Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant to step the ocean and crush us at a blow? Never! All the armies of Europe, Asia, and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth in their military chest, with a Bonaparte for a commander, could not by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge in a trial of a thousand years.”

What, then, threatens democracy?

“If destruction be our lot we must ourselves be its author and finisher.“

Now the lean lawyer pauses. He hopes he is being “over wary,” yet he sees “something of ill-omen amongst us.” Mobs are unleashing “wild and furious passions, in lieu of the sober judgment of courts.” He cites examples. A freed slave lynched. An editor gunned down. And from Mississippi, where he rode flatboats along the river, Lincoln recalls the strange fruit he saw, bodies “dangling from the boughs of trees upon every road side; and in numbers almost sufficient to rival the native Spanish moss of the country, as a drapery of the forest.”

So who should care? he asks. When a crime is committed, who cares if justice comes from a mob or a court? You do, because. . .

“Whenever the vicious portion of population shall be permitted to gather in bands of hundreds and thousands, and burn churches, ravage and rob provision-stores, throw printing presses into rivers, shoot editors, and hang and burn obnoxious persons at pleasure, and with impunity, depend on it — this government cannot last.”

Lincoln goes on to warn against tyrants. Will America be spared the ambition of a Caesar or Napoleon? An American tyrant will come, Lincoln says, “and when such a one does, it will require the people to be united with each other, attached to the government and laws, and generally intelligent, to successfully frustrate his designs.” Even if such a tyrant begins with good intentions, “that opportunity being past, and nothing left to be done in the way of building up, he would set boldly to the task of pulling down.”

Lincoln’s Lyceum Address did not put him on the road to the White House. Two decades of political and personal loss followed. As North and South careened toward civil war, mobs raged again and again. But perhaps Lincoln wasn't speaking to the America of his time. Perhaps he was speaking to America for all times. Because as Lincoln taught us, the sole guardian of democracy is “the people” themselves.

Back at the podium, he rises to his finish. Faced with “the mobocratic spirit. . . the question recurs, ‘How shall we fortify against it?’ The answer is simple. Let reverence for the laws be breathed by every American mother to the lisping babe that prattles on her lap. Let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges; let it be written in primers, spelling books, and in almanacs; let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice.” Let the law, Lincoln says, “become the political religion of the nation.”

The river flows on.