PAPA FLASH AND THE SPLINTERED SECOND

The seconds pass unbridled, rushing us onward. If only we could hold a moment, “seize the day.”

The first photography stopped time but anyone who even turned a head became a blur. By the 1870s, cameras were fast enough to settle a bet about a galloping horse — for a brief instant, all four legs leave the ground. Eadweard Muybridge’s famous photos led to the first motion pictures, but that was the plodding 1800s. Who could freeze-frame an accelerating 20th century?

Early in the 1930s, deep in a lab at M.I.T., a young engineer working with motors hoped to photograph their minute motions. But at 2,500 rpm, no camera could capture such quicksilver, so Harold Edgerton invented one.

So how did this modest engineer, with no training in photography, freeze not just 1/1000th of a second, as any camera could, but 1/100,000th, even a 100 millionth of a second?

Growing up on the Great Plains, Edgerton was raised at a horse and buggy pace. Movies did not come to Aurora, Nebraska until he was in grade school, and cameras were Brownies or other Kodaks. Edgerton got his first camera at age 15 but found it frustrating. The photos were too blurred to see anything but prairie stillness. Electricity was more interesting.

EDGERTON AT M.I.T.

Electrical engineering led Edgerton to M.I.T. By 1931, movies were talking and photography was an art, but no one knew how to freeze a world that ran faster every year. Edgerton’s doctoral thesis — “Benefits of Angularly-Controlled Field Switching on the Pulling-into Step Ability of Salient-Pole Synchronous Motors” — did not promise a photo-revolution. But an idea came to him, well, in a flash.

Imagine a light flashed thousands of times a second. Imagine a movie camera zipping film past a lens at an equally dazzling speed. Put both in a black room and. . .

Edgerton soon masterminded the instruments needed. With his mercury vapor strobe lighting the darkness for successive micro-seconds, his film captured the precise machinations of whirring motors, earning him a doctorate. Then a fellow engineer suggested he aim his strobe at a world in constant motion.

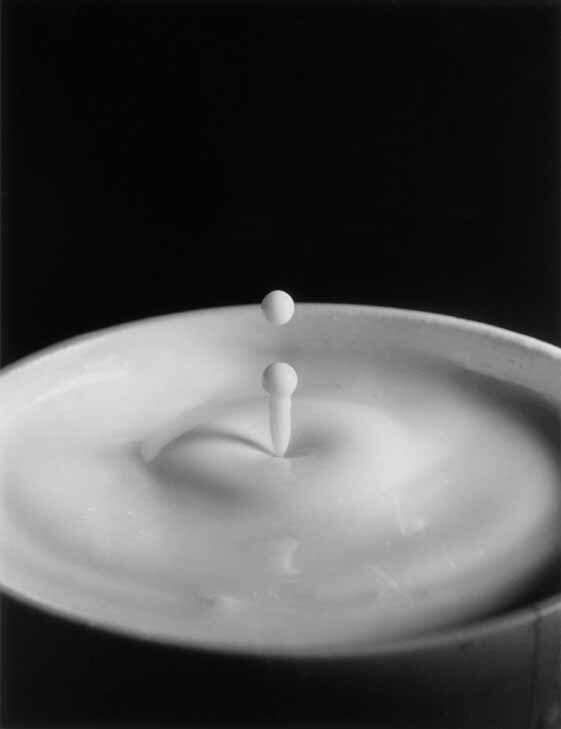

Water from a faucet. A hummingbird. A drop of milk. At 2,000 images per second, fluid movements splintered. Everyday physics paused and posed.

“I can't imagine a world without Edgerton images,” one museum curator said. “They have become such a part of the American experience that we take it for granted,"

In 1937, Edgerton’s images first captured the public imagination. In LIFE magazine, in National Geographic, at MoMA’s first photography show, here was the single moment, split, then split again, and frozen in wonder.

“DOC” BEING “DOC”

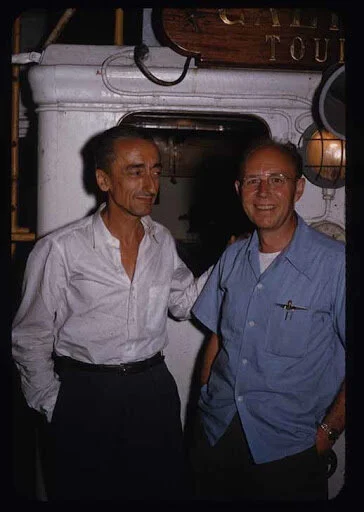

For the next 40 years, “Doc” Edgerton was a fixture at M.I.T. He found new subjects — a tennis swing, a golfer, the Moscow Circus — but his ingenuity could not be confined to a lab. During World War II, Edgerton’s cameras did night reconnaissance that reveal the location of German troops before D-Day. After the war, he worked with the Atomic Energy Commission to freeze-frame nuclear explosions. And when he improved sonar, enabling it to sweep the sea bottom, he dove in a bathyscaphe 1,700 feet into the Mediterranean, then worked with Jacques Cousteau.

Cousteau’s crew called Edgerton “Papa Flash.” Proud of the nickname, Edgerton took it on a new quest — using his advanced sonar to find sunken ships. Working with an engineering firm he co-founded, Edgerton located old whalers, a ship from the fleet of Henry VIII, and the Monitor, the Civil War “ironclad” sunk off Cape Hatteras.

THE TRICK TO EDUCATION

Back at M.I.T., Edgerton helped new generations of engineers slice seconds into ever-smaller shards. His easy Midwestern manner stood out in the edgy Eastern school. “The trick to education," he often said, "is to teach people in such a way that they don't realize they're learning until it's too late." His “family of students” found Edgerton always ready to spare “just a few micro-seconds” in consultations that often lasted hours. Spry into his 80s, Edgerton traded quips with David Letterman, often coming out on top. Watch.

When he died in 1990, the name still did not ring a bell. But with 47 patents, with photos never equalled, Papa Flash left behind more than split seconds. His work did the impossible — not just seizing the day but splintering the moment.

Edgerton “was never trained as an artist in any way; he was only trained as a scientist,” one art professor noted. “But there's an artist's mind at work, too. You have some jock sweating and smacking a ball while a scientist is recording it, and all of a sudden you end up with art, poetry and mysticism. It's just amazing."