CRADLE OF MOUNTAIN CULTURE -- APPALSHOP

JEREMIAH, KY — The film crew was wrapping up when the trouble began.

Excited about the day’s footage — weary miners on rickety porches, barefoot kids in shacks — crew members hardly noticed the grizzled old man approaching. “Get off my property!” Hobart Ison shouted. “NOW!” Then he pulled out a .38 and shot the cameraman in the chest. Hugh O’Connor’s last words began with “Why?”

In 1967, Appalachia was synonymous with American blight. The War on Poverty was sending young volunteers into these hills, trailing clouds of journalists. So when the mountain man killed the cameraman, locals understood. “They’ve made enough fun of mountain people,” one told the Lecher County D.A. “Let me on the jury, Boone, and I’ll turn him loose.”

Enough! Enough of stereotypes. Hillbillies and Hatfields and McCoys. Why couldn’t Appalachia tell its own story?

Shortly after Hobart Ison’s trial ended in a hung jury, another stranger with a camera came to Appalachia. But Bill Richardson, fresh out of Yale, did not point his camera. He taught people how to use it. His idea was “to offer a counter narrative to the one that made Eastern Kentucky the poster child for American poverty.” Renting a storefront in Whitesburg, Richardson set up shop — Appalshop.

“There was a sense of curiosity,” recalled Herb Smith. “A lot of energy and anger at the failure of the American government to help us. And we were high school kids, fascinated by all that film gear.”

A half century later, now hunkered down in an old Coca-Cola plant on the edge of Whitesburg, Appalshop is a beacon in a beloved and beleaguered region. Coal mining is endangered. Opioids make headlines. Poverty tightens its grip. But against these odds, the people of Appalachia continue to create a river of music, art, and tradition. And that river flows right through Appalshop.

“No institution has done more to enhance the self-awareness and self-respect of Eastern Kentucky and all of Appalachia.”

With grants from the NEA, the NEH, the MacArthur Foundation and others, Appalshop has crafted a collective portrait of this unique region — its music, its life, its heart. “There have been years, as we say, of thin cows and years of fat cows,” said Herb Smith, who has made 60-some Appalshop films. “But we have learned to gear down and carry on.”

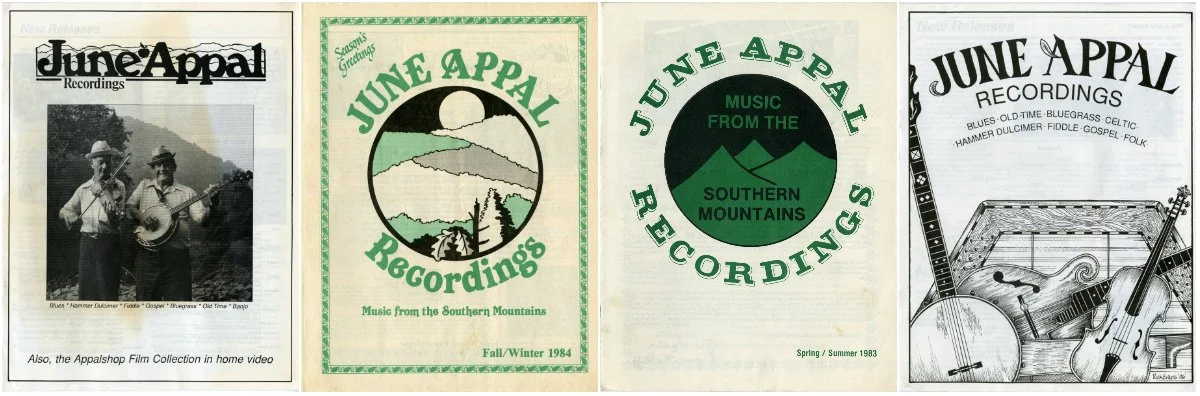

Appalshop’s cultural celebration includes: CDs of mountain music and storytelling on the June Appal label; books displaying quilts, carvings, and other crafts; a regional theater, a Mountain Tech Media lab, and films, — 120 and counting.

Appalshop films range from short profiles of musicians and artists to longer documentaries about social issues. Prison abuse. Women’s shelters. Marijuana as cash crop. Other films profile the hardships of mining, the endurance of old-timers, the hope in girls basketball. Appalshop films have screened on PBS, at Sundance, at MoMA and other museums. And you can screen them through the streaming service Vimeo.

Bill Richardson’s “portable” camera weighed 20 pounds. Today, anyone with a phone can shoot a movie, which is why Appalshop’s summer Appalachian Media Institute teaches the finer points of filmmaking. An annual Seedtime in the Cumberlands music fest draws crowds. Appalshop’s online archive lets you browse thousands of artifacts. And WMMT-FM features banjos, fiddles, and plenty of mountain talk.

Still, the old stereotypes persist. “Hollywood likes stock characters,” said Herb Smith. “Cowboys and Indians are easy characters everyone thinks they know. It’s the same with hillbillies. You think it’s over and then, lord have mercy, here they come again.”

But rivers, of culture and of rainwater, have a way of overflowing. And Appalshop was devastated by the recent floods in Kentucky. Nearly a month later, with the waters subsided, Appalshop and a team of volunteers are still assessing the damage. Want to help?

In gratitude, Appalshop thanked volunteers and noted that the apple tree outside its first floor offices “is still standing with its young roots intact. Despite record floodwaters of over twenty feet, our little apple tree still stands, bearing fruit and hope.”

As the old song says, “it’s a long way to Harlan,” but Appalshop makes the journey a two-way trip. And with a dozen young staffers now buzzing around the old bottling plant, Smith sees “a generational transition. It’s a charge to see them pull it off.”

Hobart Ison, finally sentenced to ten years, served one year before parole. In 2001, an investigation explained why locals seemed to sanction the murder. Not from some “clannish suspicion of outsiders“ but “because they perceived the prying eyes of reporters to be an assault on manners, common decency, and the integrity of their communities.”

“Americans have been suckered,” Herb Smith told The Attic. “News shows portray all these poor mountain people. Partisan politics continues to divide us. It only makes our job at Appalshop more important. If you just have these cardboard characters, we will never deal with the reality.”