THE BOOK THAT BEFOULED BASEBALL

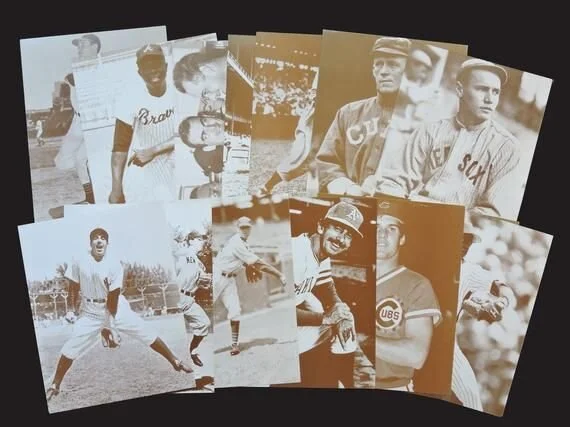

Fifty springs ago, another baseball season began. Another jillion games. Another All-American legion of men in boys’ uniforms. Another shelf of books — From Ghetto to Glory. The Glory of Their Times. Baseball’s Shrine: The Hall of Fame.

And then that summer, a single book gave our “national pastime” a rousing Bronx cheer. The book was written not by some slugger but by a fading relief pitcher toiling for a lousy team. Forget glory. Shut down your Shrine. Enter Ball Four.

Jim Bouton had been a 20-game winner for the dynastic New York Yankees. Then an arm injury left him to bounce around the majors on the game’s hardest pitch — to throw, hit, or catch — the knuckleball. So in 1968, when Bouton began jotting notes on another hapless season, he told no one. But a New York sportswriter got word and asked to see the notes.

“I didn’t know the value of it,” Bouton recalled. “I was just really sharing the nonsense. Every once in a while, I would transfer the notes to audio and send in my tapes. I’d call Shecter and say, ‘Is this interesting?’ And he’d say: ‘Are you kidding? Keep going!’”

The nonsense included stories every sportswriter was sworn not to tell. Here were “heroic” New York Yankees prowling a hotel roof to “shoot beaver” by peeping into windows. Here were veteran managers saying the stupidest things — “Attaway to stomp ‘em. Stomp the piss out of ‘em. Stomp ‘em when they’re down. Pound that ol’ Budweiser into you and go get ‘em tomorrow.”

And here was a fresh side to the grand old game — fun. Players shouting “Ding-dong!” when a catcher took a foul ball to his protective cup. One player hitching up his pants, saying, “I add 20 points to my average if I know how bitchin’ I look out there.”

Above all, here was a proud man wrestling with failure. Ball Four begins “I signed my contract today to play for the Seattle Pilots at a salary of $22,000 and it was a letdown because I didn’t have to bargain.”

By mid-summer 1970, Ball Four was the talk of a war-weary nation grown jaded about hard boiled men in uniform. David Halberstam saw “a book deep in the American vein.” LIFE observed, “Top dollar adults were getting awfully tired of the short-haired, cliche-bearing prigs we used to get.”

Other players had published season-long diaries, but none like this. Bouton told of teammates guzzling amphetamines called “greenies.” He remembered Mickey Mantle, hungover on the bench, asked to pinch hit. Somehow, Mantle hit a homerun and dragged himself around the bases. “They’ll never know how hard that was,” Mantle said back in the dugout. But now they knew.

Ball Four sold a half million copies that summer, 5 million more in paperback. But players shunned Bouton. One sportswriter called him a “social leper.” And commissioner Bowie Kuhn, blasting Ball Four as “detrimental to baseball,” called Bouton into his office to sign a statement blaming his co-author for making it all up. Say it ain’t so, Jim!

“When I politely told the Commissioner what he could do with his statement, he turned a color which went very nicely with the wood paneling.”

Baseball had thrived on legend. The Iron Horse. Joltin’ Joe. Stan the Man. All those baseball cards, trophies, autographs. Bouton scoffed, telling one self-righteous interviewer, “I don’t believe it’s necessary to have a false image.”

Far from being “detrimental to baseball,” Ball Four, as the New York Times noted, “breathed new life into a game choked by pontificating statisticians, image-conscious officials, and scared ballplayers.” Further tell-all memoirs dragged the sacred sport into the modern world. Fans relished in players’ struggles not just to hit a slider, but to face their flaws — drug use, paternity suits, and a general jerkiness. “Why do ballplayers have to take drugs and have girlfriends in the first place?” Bouton later asked. “This may come as a shock to some people but it’s because they’re human beings. Young human beings. Think of a ballplayer as a fifteen-year-old in a twenty-five-year-old body.”

Bouton became a sportscaster, actor, and writer, but he could not resist attempted comebacks. Most mired him in the minors but one glorious night in 1978, before a sellout crowd in Atlanta, his knuckleball danced through six scoreless innings. His last major league game — and win — was “my greatest night ever in a baseball uniform.”

In 1995, Ball Four was the only sports book among the New York Public Library’s Books of the Century. Fans long remembered the players Bouton had humanized, but the book’s most enduring tribute is to baseball itself.

“You see,” Bouton concluded his chronicle, “you spend a good deal of your life gripping a baseball, and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.”