THANK YOU, RAY BRADBURY!

WAUKEGAN, IL — SUMMER 1922 — Just over a century of Augusts ago, a boy was born in a town straight out of Norman Rockwell. Heeding adult advice, he might have become a teacher or insurance man. Instead, raised on flights of fancy, Ray Bradbury grew older but never old.

Generations of readers still see the future through his lens. When books are banned, we think of Fahrenheit 451. When space beckons, we remember The Martian Chronicles. Every tattooed hipster suggests his Illustrated Man. Every giant TV or AI bot recalls a Bradbury story.

Twenty-seven novels and 600+ stories. Eight million copies in 36 languages. But Bradbury’s reach lies not in numbers but in words. Though his prose will never make them forget Faulkner, he is, like the best writers, a way of perceiving the world. And that world began with wonder.

Planted on the plains north of Chicago, Waukegan scarcely seemed wondrous, but Bradbury’s boyish enthusiasm made it magical. His childhood, he recalled, was “one frenzy after one elation after one enthusiasm after one hysteria after another.” Buck Rogers and Tarzan. Carnivals and floating “fire balloons.” A caped Mr. Electrico who proclaimed “Live forever!”

Then Bradbury’s father, seeking work during the Depression, moved the family to L.A. There the boy became starstruck. He roller skated past Hollywood homes, hoping for a glimpse of the stars. He snuck into movie after movie. And he wrote.

By high school he was writing a thousand words a day. Unable to afford college, he “went to the library three days a week for ten years.” “Graduated from libraries,” he sold his first story to a pulp magazine for $15. Ideas, he often said, leapt at him each morning, saying “Write me! No, write me!”

His big break came after the war, which his weak eyesight kept him from joining. “The Homecoming” caught the eye of a young editor, Truman Capote. The story appeared not in pulp but in Mademoiselle, earning Bradbury an O. Henry Prize. In 1947, with a dozen stories in hand, he took a bus to Manhattan where an editor suggested he gather his space stories into a novel. Call it, maybe, The Martian Chronicles.

For anyone who read it at an impressionable age, the title brings back precious moments. Late nights under the covers with a flashlight. Long hours in school with the tattered paperback hidden behind a history text. Pages that seemed to turn at will. Bradbury had channeled wonder into stories that would haunt us.

In “There Will Come Soft Rains,” he envisioned today’s “smart houses” with automatic appliances making breakfast and greeting the day. But this house keeps working even after “the bomb” etches human silhouettes onto a wall. In “The Veldt” he foresaw a child’s bedroom, wired to virtual reality and turned into a jungle with lions that seem eerily real. And in his second novel, he dreamed a world that is too much with us now.

In 1950, distracted by his young daughters, Bradbury fled to the library at UCLA. Down in the basement, feeding dimes into a pay typewriter, he banged out 25,000 words in nine days. Between sessions, he strolled upstairs, marveling at the books, opening them to hear their ancient voices. The battle between timeless wisdom and mindless pop culture exploded into Fahrenheit 451.

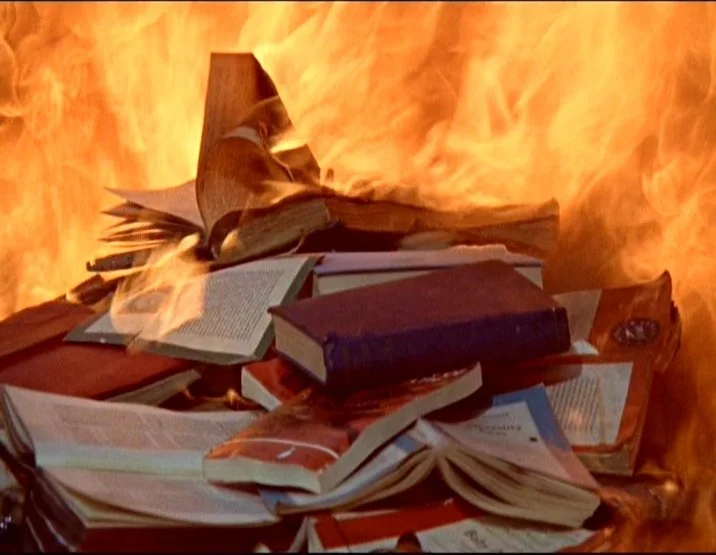

“It was a pleasure to burn,” the book begins. The story soon descends into a nightmare world of wall-sized TVs, empty people distracted from empty lives, and firemen hunting down books and burning them. When one fireman hides a book in his home, the fire comes for him. Framed on millions of TVs in a chase scene many later likened to O.J. Simpson’s White Bronco ride, Montag flees into an underground where rebels hold books in their heads, waiting for war and a restart. While some still see the book as anti-censorship, Bradbury said it’s really “about TV turning people into morons.”

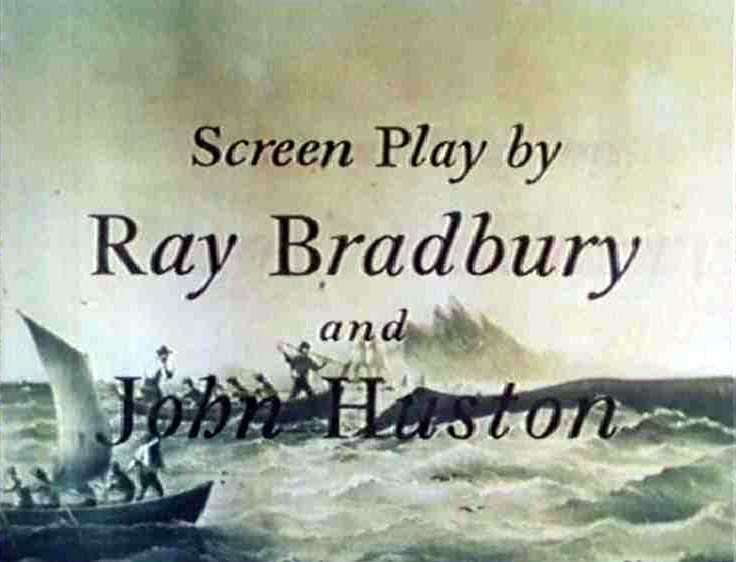

The New York Times hailed “Mr. Bradbury’s account of this insane world, which bears many alarming resemblances to our own.” Bradbury was praised by poets, summoned by Hollywood directors. He co-wrote the screenplay for “Moby Dick,” then wrote for TV and the stage.

Though he soared on imagination, Bradbury lived a pedestrian life. He and his wife, Marguerite, the only woman he ever dated, raised four daughters in the same house they bought in 1947. He never used a computer, rarely flew, never learned to drive. But he would speak to any group that would pick him up at home. Audiences came away enchanted.

Late in life, when technology caught up to his stories, he grew concerned. The Internet, he said, is “a big distraction.” E-books are not books. “Three companies have offered to put books by me on the Net. And I said, ‘If you can make something that has a nice jacket, nice paper with that nice smell, then we’ll talk.’”

Long before his death in 2012, Bradbury’s legacy was secure. Apollo astronauts named a crater for Dandelion Wine. NASA’s Mars rover touched down at “Bradbury Landing.” He received awards, prizes, and honorary degrees. Yet as a movie fan, he most cherished his star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame.

So thank you, Ray Bradbury. Thanks for enthralling us with what might be. Thanks for warning us against turning ourselves over to, or into, machines. The final words should be yours. From Fahrenheit 451:

“Stuff your eyes with wonder. Live as if you’d drop dead in ten seconds. See the world. It’s more fantastic than any dream made or paid for in factories.”