THE MOHAWKS AND 'HIGH STEEL'

All right, the contractor told the Mohawks. Let us build a bridge through your reservation, and we’ll give your young men jobs. Odd jobs, loading and unloading, cleaning up. The Mohawks went to work, but it wasn’t long before they rose.

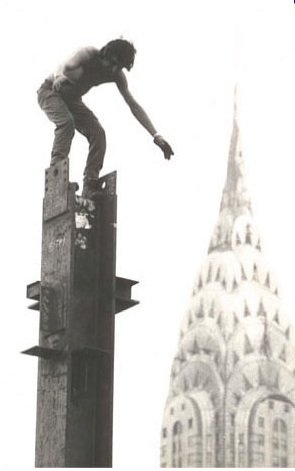

Workers marveled to see natives out on the half-built bridge, climbing, soaring, scrambling. “If not watched,” one engineer remembered, “they would climb up into the spans and walk around up there as cool and collected as the toughest of our riveters . . . These Indians were as agile as goats.”

Men who could toil at dizzying heights, heating red-hot rivets, hammering and welding, were rare. The noise drove some back to earth. The distance straight down terrified others. So when someone said, “why not try Mohawks?” the First Americans began building the New World.

Look up at the nearest skyscraper, out across the nearest bridge. Whether you’re in New York or Boston, San Francisco or L.A., chances are that “high steel” was riveted by a Mohawk. For more than a century, these “Fearless Wonders” have amazed even fellow workers with their daring and dexterity. Contrary to legend, they are not immune to that clutch of fear that comes from looking downnnnnnn. It was, one said, “a question of dealing with the fear.” And then, of course, pride.

Back in 1887, when the Canadian Pacific bridge was finished, the first Mohawk riveters moved downriver to another half-built bridge. Soon they were training fellow Mohawks, forming crews, fanning out across the industrial landscape. Buffalo. Cleveland. Detroit. By 1907, the small Kahnawake tribe had 70 full-time riveters. Then came what Mohawks still call “the disaster.”

Engineers ignored warnings. The bridge stretching across the Quebec River was shaky, imbalanced. In August 1907, the bridge collapsed, killing 96 workers, including 35 Mohawks. “People thought the disaster would scare the Indians away from high steel for good,” one remembered. “Instead it made high steel much more interesting to them. It made them take pride in themselves that they could do such dangerous work.”

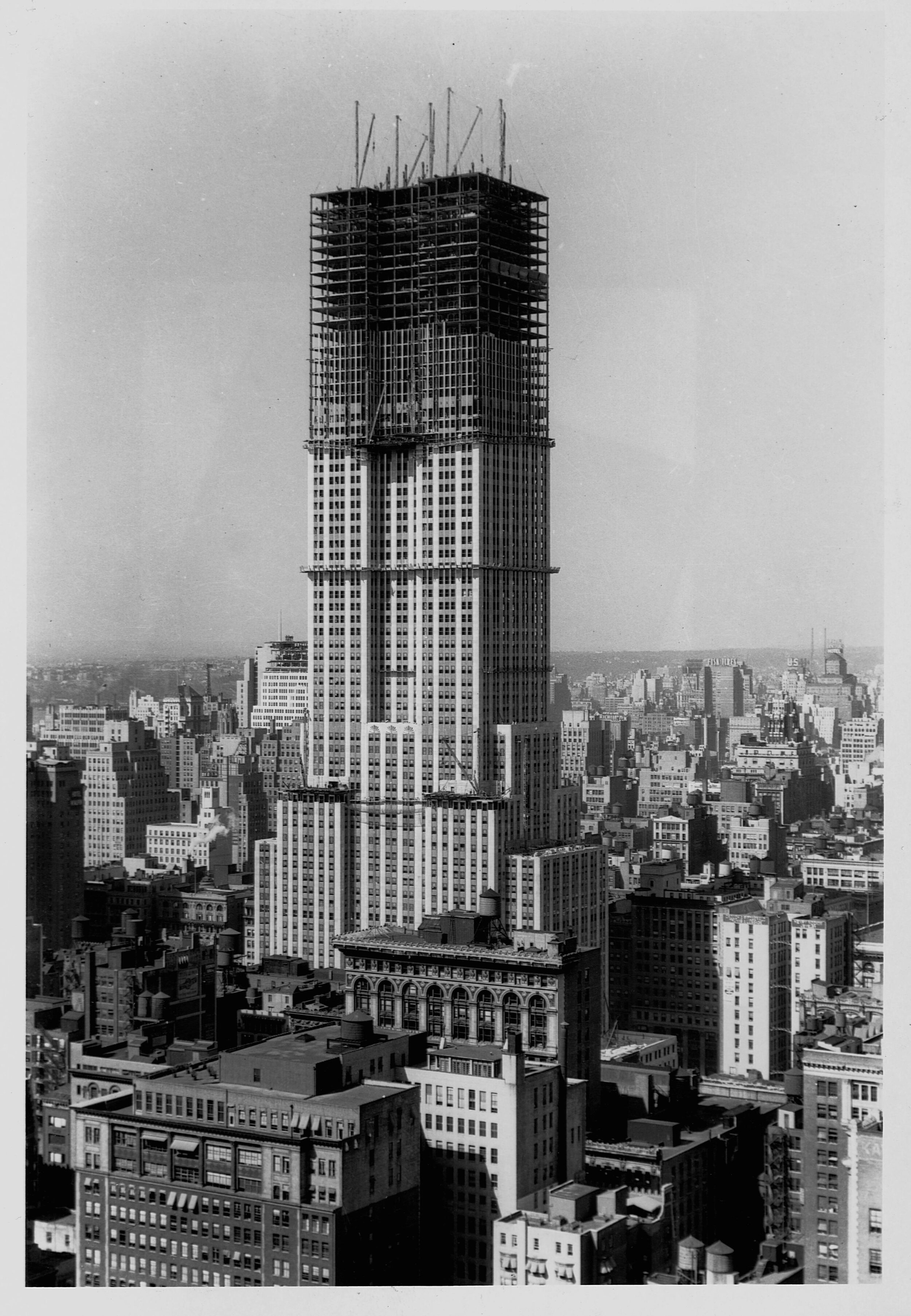

In 1915, Mohawks began commuting from their small reservation on the St. Laurence to the sprouting city of Manhattan. Soon Mohawks were seen high above the Hudson. In the early 1920s, when immigration laws tightened, one was deported. Others sued. Courts found a 1794 treaty giving Northeast natives free roaming rights across the border. And Manhattan bloomed.

Mohawk riveters worked on the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, Rockefeller Center, the Triborough Bridge. . . People watched in wonder. “Like little spiders they toiled,” one newspaper wrote, “spinning a fabric of steel against the sky.”

Back on the ground, some 300 Mohawk riveters settled in Brooklyn, turning the neighborhood of North Gowanus into “Little Kahnawake.” Bars imported Canadian beer. Grocery stores stocked the flour Mohawk wives used for o-nen-sto — corn soup, with kidney beans and a hint of maple. “If you were breathing your last,” one riveter said of the soup, “if you had the rattle in your throat, and the wind blew you a faint suggestion of it, you’d rise and walk.”

Mohawks ate together, drank together. Each weekend, men new on the job made the 12-hour journey home. “An Indian high-steel man, when he first leaves the reservation to work in the States, the homesickness just about kills him,” Orvis Diabo recalled. “The first few years, he goes back as often as he can.” But veterans soon roamed farther, earning a reputation for going wherever high steel was going up.

One New York foreman remembered finishing a building, ready to start another but the Mohawks got word of job in Hartford. Same pay, same hours, but they took off. A year later the foreman met the men on a job in Newark. He asked about Hartford. They hadn’t gone. “We went to San Francisco. We went out and worked on the Golden Gate Bridge.”

Time eventually brought each Mohawk riveter down to earth. “One fine morning,” Diabo said, “he comes to the conclusion he’s a little too damned stiff in the joints to be walking a naked beam five hundred feet in the air.”

Some 200 Mohawks worked on the World Trade Center, but by the 1980s, Mohawks found more jobs in Montreal than in Manhattan. When Brooklyn rents soared, Mohawks went home. Some 100 remain in Manhattan, still working in “high steel.” Mohawks were at work on 9/11 when planes flew low overhead. Mohawks were among the rescuers picking through the rubble. And Mohawks were at work again building the Liberty Tower.

“I heated a million rivets,” Orvis Diabo said. “When they talk about the men that built this country, one of the men they mean is me.”