VIVIAN MAIER -- THE MYSTERY WOMAN WITH THE CAMERA EYE

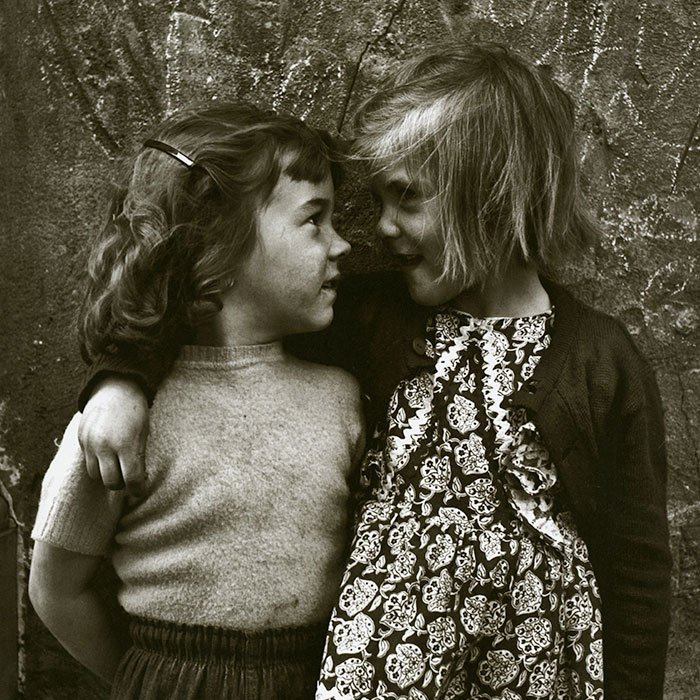

CHICAGO, 1958 — Only the children noticed the nanny. Dressed in a felt hat, clunky shoes, and frumpy clothes, she was “a real life Mary Poppins” — fun, adventurous. And wherever they walked, she carried a camera.

Adults thought she was weird. She seemed French, with that accent. She had no family, no friends. Called herself “the mystery woman.” And that camera! Did she have to take pictures all the time?

Vivian Maier spent her final years on a park bench, sometimes dumpster diving. But within weeks after her death in 2009, those photos, some 150,000, came to light. What they revealed was a startling, inventive, probing photographer, soon to be the talk of the art world.

When John Maloof bought a box of negatives at a storage auction, he was simply looking for photos to illustrate his book about a Chicago neighborhood. Maloof, who had grown up going to flea markets, knew that black-and-white negatives were usually worthless. He figured most would end up in the trash. Then he held a few up to the light and saw. . .

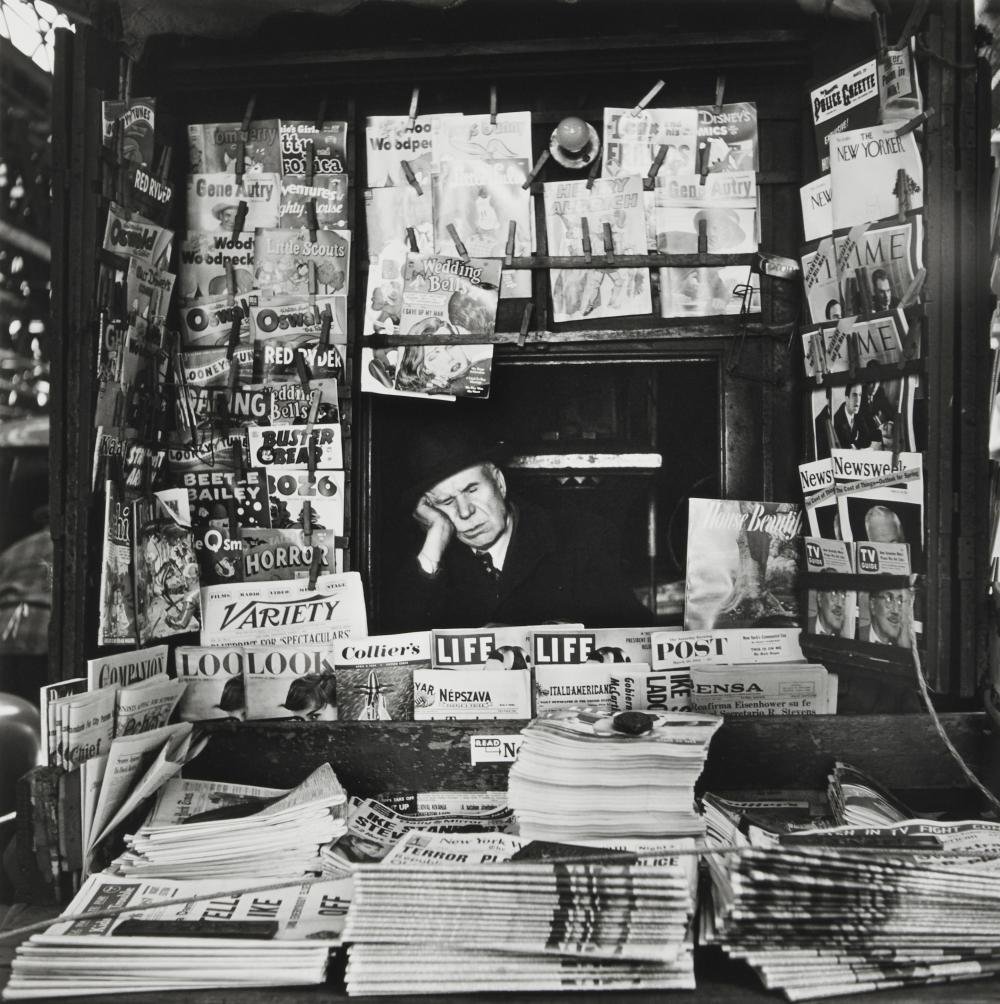

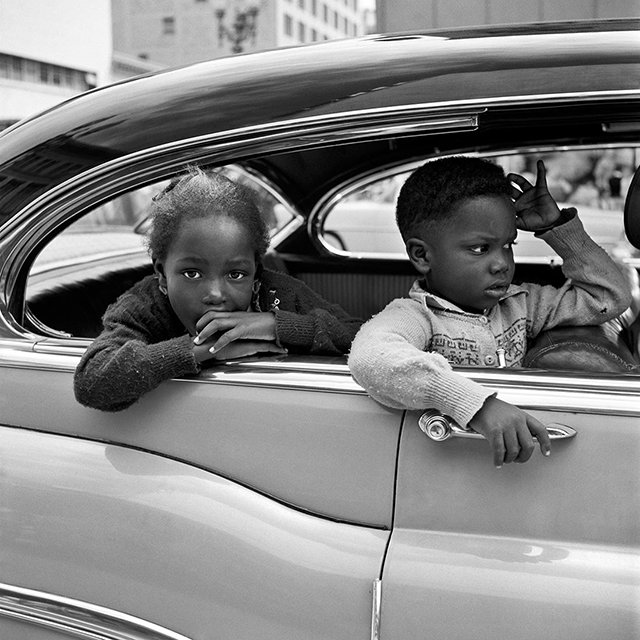

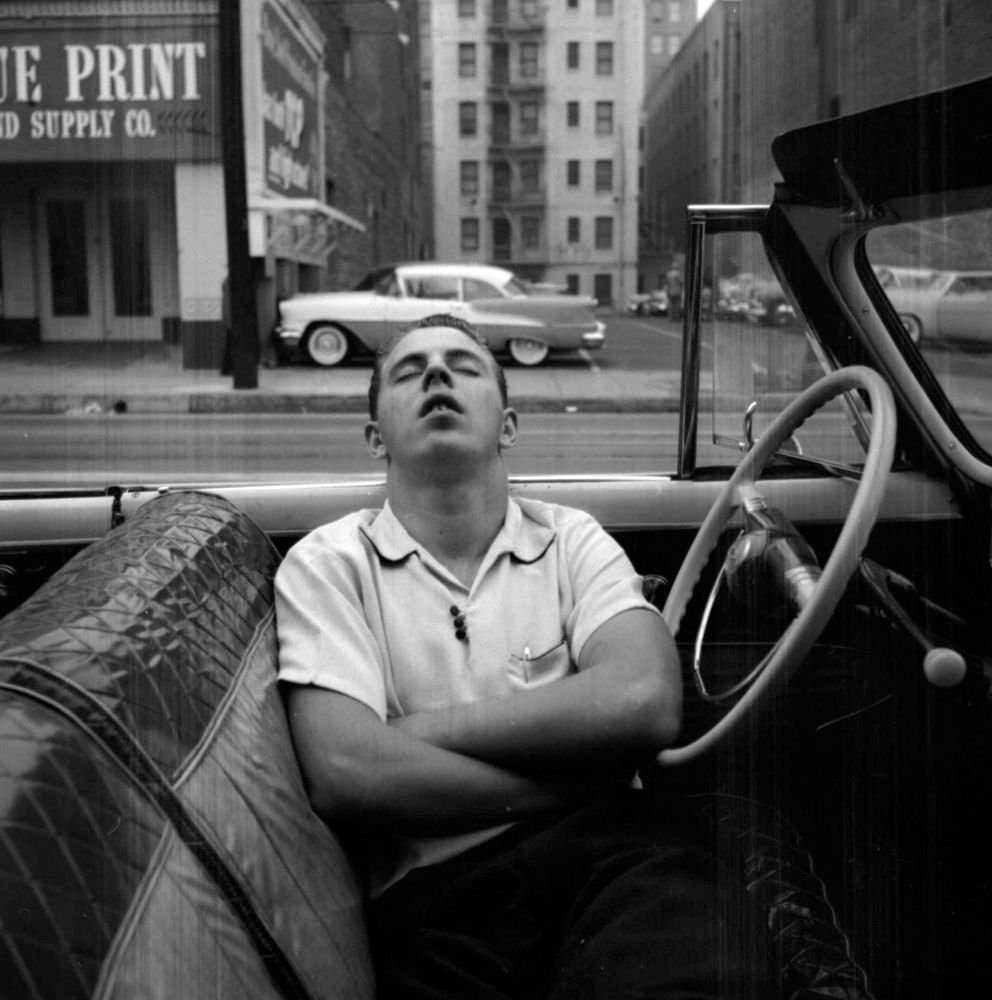

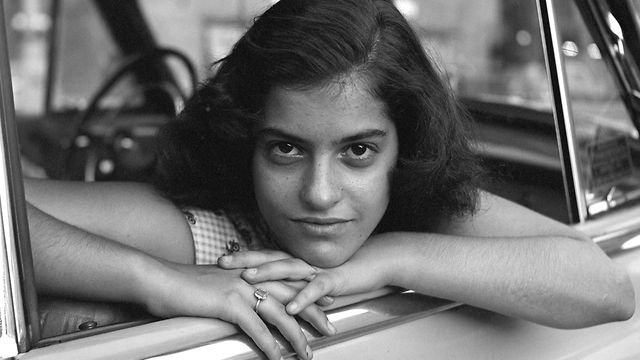

Stunning portraits of people on the street. Grizzled old men. Tight-lipped socialites. Children crying, laughing, playing. And people caught off guard, just being people. “I didn’t know it was good,” Maloof remembered, “but I knew I thought it was good.”

Told that the negatives had belonged to an old woman named Vivian Maier, Maloof Googled the name. Nothing. Then in a second box, he found an address. Getting the phone number, he called.

“Oh, she used to be my nanny.”

Fascinated, Maloof began tracking down other boxes, reassembling a life. But he wondered, “what do I do with this stuff other than giving it away?”

He scanned 200 photos into a blog. No reaction. He contacted MoMA and the Tate Modern, sent samples. Polite rejections. Then he put a few dozen photos on Flickr, and overnight, Vivian Maier went viral. But who was “the mystery woman?”

Maloof’s relentless detective work revealed the story. She was born in New York, 1926, to a French mother and Austrian father. But when the father vanished, the mother took the girl back to her village in the French Alps. Then back to America. Then back to France. Vivian grew up suspicious of men, most likely for the all too common reason. Determined to live free., she worked in a sweatshop, then moved to Chicago and answered an ad for a nanny. No one knows when she bought her first Rolleiflex.

“She was very opinionated about how children should spend their time,” said one of her employers in the documentary “Finding Vivian Maier.” “And mainly how they should spend it was out and about with her.”

While parents worked or played, Miss Maier took the kids to the movies, to a cemetery, to a forest to pick wild strawberries. Roaming Chicago, the kids had great fun, but Miss Maier often stopped to take photos. Anything might catch her eye. Bums on a corner. The lattice of a fire escape. Herself in a reflecting window.

She kept the negatives in boxes. As she aged, and began to hoard newspapers, political buttons, tchotchkes, the boxes piled up. “I have to tell you that I come with my life,” she told one couple, “and my life is in boxes.” But except for a year-long trip around the world, Vivian Maier lived on — in boxes, in photos, in upstairs rooms she kept off limits.

The more John Maloof learned about the mystery woman, the more he wondered. Why didn’t she try to display her work? She did, once, writing to a studio in her French hometown, asking them to print her photos. “They are not bad, if I do say so myself.” The connection fell through.

And why did she use fake names — V. Smith and others. “She was private. Period,” one employer said. And why did she. . .

Answers were few but as her work came into the world, everyone agreed. Vivian Maier was one of America’s great street photographers, on par with Robert Frank and Walker Evans. When Maloof debuted her work in a Chicago gallery, a record crowd attended. Then came more shows, the Oscar-nominated documentary, books, biographies, and museum exhibits throughout America and Europe.

The private woman has now been revealed. Not everyone thinks this was a good idea. “These were her babies,” a former employer said. “She would never have put her babies on display.” But another disagreed. “I don’t think she took all those photos to allow them to dissolve into dust. She wanted them to be seen.”

Mysteries remain. John Maloof still has boxes and boxes of photos, 8 mm. movies, audio tapes, all the touchstones of a sad but artistic life. What would Miss Maier think? Perhaps that, finally, her turn came.

“We have to make room for other people,” she says on one tape. “It’s a wheel — you get on, you have to go to the end, and someone else has the same opportunity to go to the end, and so on, and somebody else takes their place. And now I’m going to close and quickly run next door to do my work.”