HOW TO SPEAK AMERICAN -- THE BASICS

PHILADELPHIA, 1781 — America was still fighting the Revolution when the American language took its first hit. The critic had solid street creds. John Witherspoon, president of Princeton, had served in the Continental Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence, but he was coming to loathe his new country’s new language.

These Americans, Witherspoon lamented in a Philadelphia newspaper, spoke as if the King’s English no longer applied. They said “knowed” for “knew,” “drownded” for “drowned.” They spoke of “fellow countrymen,” as if there were any other kind. They used “winder” instead of “window,” made up words like “bilk” and “bamboozle,” and salted their speech with “thing.” “This here thing.” “Not the thing.” “Quite the thing.”

Americans in 1781 treated Witherspoon as we still handle the cranks who snub our peculiar patois. They went right on talking. And in the 240 years since, the language that is uniquely “American” has taken over the world.

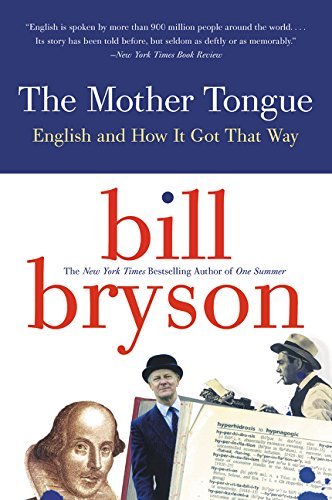

“Germans talk about ein Image Problem and das Cash-Flow,” Bill Bryson wrote in The Mother Tongue. “Italians program their computers with il software, French motorists going away for a weekend break pause for les refueling stops, Poles watch telewizja, Spaniards have a flirt, Austrians eat Big Mäcs, and the Japanese go on a pikunikku.”

So what is it about the American language that makes it so free, so fun to listen to or speak. The story that starts with denunciation “morphs” into celebration.

Like America itself, American is a hybrid. The language, like (most of) the people, welcomes new faces, new phrases. Other languages borrow from American but American borrows from the world. American, Walt Whitman wrote, is “the accretion and growth of every dialect, race, and range of time. . . a sort of universal absorber, combiner, and conqueror.”

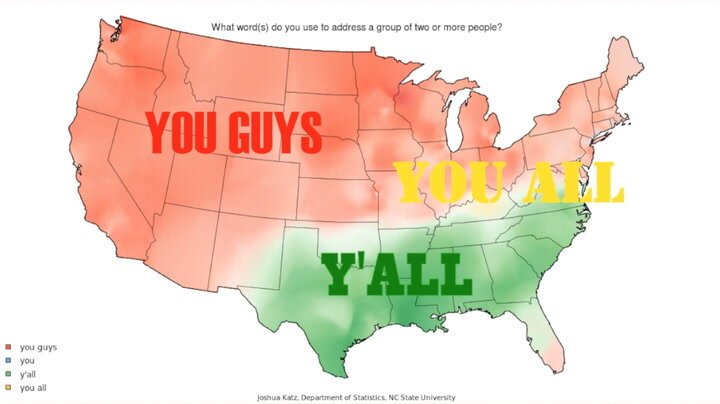

Hence the common terms born far from home turf. Tycoon and honcho (Japan), patio and barbecue (Mexico), mosquito and aficionado (Spain), bayou and entrepreneur (France), safari (Arabic), guru (Sanskrit), angst and wanderlust (German), klutz, bagel, dreck, and others from Yiddish. And then there are regionalisms, from the Southern y’all and “might could” to our myriad ways of saying sandwich, soda, and a simple “how ya’ doin’?”

Along with borrowing, Americans are aficionados at slang. Every language has its slang, yet America’s abounds because it grows from all the right conditions. The Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang sees slang flourishing wherever there are A) strict linguistic standards that slang users can defy; B) assorted “out-groups” eager to define themselves by how they talk; C) interaction between in- and out-groups to spread the latest argot; and D) rebellious types using slang to sound “cool.”

Do I hear an “Oh, say can you see?”

So if, as Stephen Pinker writes, there is a “language instinct,” Americans have an instinct for improv, for wingin’ it, for going with the flow. American slang, initially expanded by Native-American words such as skunk, canoe, and tomahawk, is these days fed by slang from the military (R & R, boondocks, snafu), the tech world (interface, hacker, blog), and above all, black culture.

“From ‘the bomb’ to ‘holla’ to the very short-lived ‘YOLO,’” the Huffington Post observed, “black slang words often go through the cycle of being used by black people, discovered by white people, and then effectively ‘killed’ due to overuse.” But although nitty gritty and right on have come and gone, some black terms have stuck around. Dis, bootie, bush league, and of course, 24/7.

Slang, the linguist S.I. Hayakawa noted, is “the poetry of everyday life.” Yet the poetry comes with risk. Time was when the average American might hope to keep up with the latest “hip” phrases, but in the age of those relentless slang-feeders — cable TV and the Internet — slang “grows like Topsy.” (What, no one says that anymore?) Use the freshest slang and you are, in that evergreen encomium, cool. Use last year’s slang and you’re just lame, toast, history, just sooo 2017.

As I found out in 2017 when addressing a high school graduation. Urging grads to turn away from their screens, I said, “the scariest words in English are ‘Netflix and chill.’” Later I was informed that “Netflix and chill” had come to mean sex. Dude, did I feel dinosaurish.

Dozens of online slang dictionaries strive to be current, but not even websites can keep up with American slanguage, now changing not by the month but by the hour. Yet many terms that started as slang have come into common usage. Along with 24/7, these include blimp, blizzard, disc jockey, G.I., hijack, jazz, jitters, even OK.

And so, American marches on. Our peculiar language, Walt Whitman noted, “is not an abstract construction of the learned, or of dictionary makers, but is something arising out of the work, needs, ties, joys, affections, tastes of long generations of humanity and has its bases broad and low, close to the ground.”

Somebody say amen. Right on. True ‘dat. Or whatever.

TO READ MORE “SPEAKING AMERICAN” CLICK HERE