MENCKEN GIVES 'AMERICAN' A FAIR SHAKE

BALTIMORE 1917 — Even from upstairs, he can hear the lingo on the street.

“I’m tellin’ ya, Jake, she’s a dilly.”

“Don’t be a simp, Al. She’s on the make. She’ll nickel and dime ya’ to death.”

“Aww lay off, why don’cha? You’re jinxin’ me.”

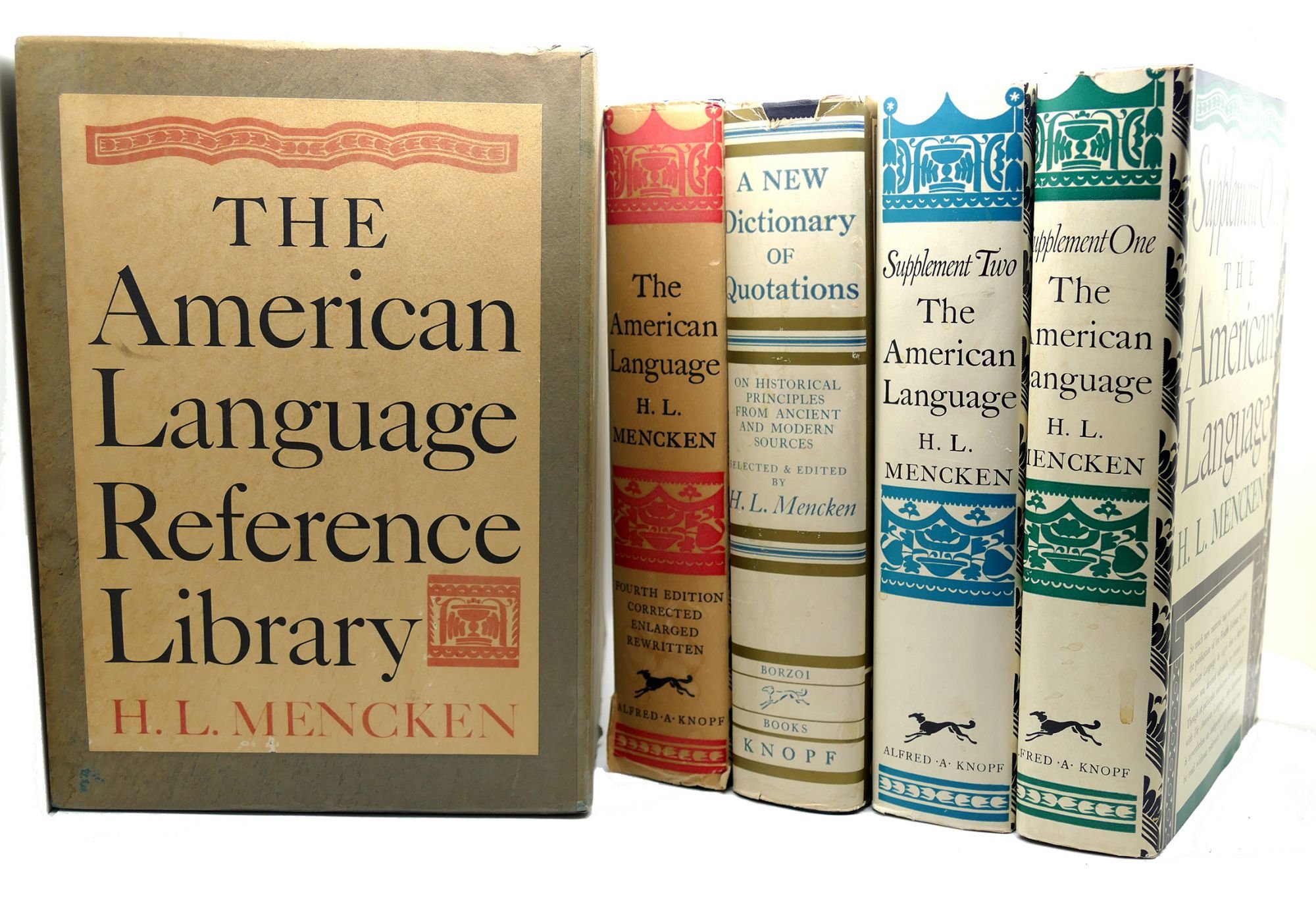

Webster had his dictionary and Twain his dialects, but it took the sourest of cynics to celebrate the soul of the language called American. For two dark years, as war and pandemic raged, H.L. Mencken studied, cherished, and catalogued the speech of the everyday folk he called “the booboisie.” The result was The American Language. Still consulted by scholars and amateur lovers of lingo, Mencken’s work, one biographer wrote, is our “declaration of linguistic independence.”

Henry Louis Mencken, raised in an immigrant household, speaking German before he spoke English, was an unlikely linguist. Though he took one class in journalism, he took none in linguistics because there were none. Before Mencken, the study of the vernacular was left to pedants snooting at the “low” vulgarisms of the common people while proudly promoting either the King’s English or Webster’s.

“No professional scholar of the time would have dreamed of presenting a discussion of the totality of American English,” one linguist later wrote.

“The American likes to make his language as he goes along.”

But Mencken never saw himself as a scholar, merely “an inquirer.” After reading Huckleberry Finn at age nine — “the most stupendous event of my life” — he opened his ears to “Americanisms.” His love of “the queer words which go into the making of ‘United Statese” surfaced in his early columns for the Baltimore Sun.

In 1910, he asked, “Why doesn’t some painstaking pundit attempt a grammar of the American language. . . English, that is, as spoken by the great masses of the plain people of this fair land?”

No pundit would stoop so low, but when the U.S. joined World War I, Mencken’s German ancestry “made journalism out of the question.” So in the spring of 1917, he holed up in his Baltimore home and began his studies. First he had to weed through “absurd efforts to prove that no such thing as an American variety of English existed.” Then he knuckled down, put his nose to the grindstone, busted his ass. . .

On into 1918 the war raged, its carnage soon capped by the Spanish flu. “All you could see from our house was funerals,” Mencken’s brother remembered. While burying twenty friends, Mencken labored on, reading, writing, appreciating. After defining “The Two Streams of English,” he set out along the American branch, recording the earliest “loan words” borrowed from native tongues. Skunk, muskrat, moccasin, podunk.

The American stream soon swelled, rushing Mencken into chapters on jargon, expletives, proper names, slang, and finally “The Future of the Language.”

Neither Mencken nor his publisher expected The American Language to sell. Just 1,500 copies were printed, but reviews hailed Mencken as “the Christopher Columbus of Americanese,” comparing him to Webster and Samuel Johnson. Far from being a dry tome, critics noted, The American Language displayed “the obvious delight“ Mencken took in how his fellow Americans talked.

He loved not just colorful words — from abnormalcy to zowie his glossary fills 95 pages — but how they evolved. Verbs crafted “by torturing nouns with harsh affixes, as to burglarize and to itemize.” Hybrids shortened from cumbersome terms. Bunk from buncombe. Beaut from beauty. Copter from helicopter. . .

Mencken’s greatest gift, however, was a broad, democratic acceptance. “The learned” might scoff at double negatives but Mencken relished their flavor, delighting even in triple negatives — “I ain’t never done nothin’” — spiced by a final “nohow.” He honored family names and place names, “forbidden words” and portmanteaus. Roughneck. Cheapskate. Sweatshop.

When The American Language drew praise, even from “the academic idiots,” Mencken considered his task finished. “Never again! Such professorial jobs are not for me.” But because language evolves, his book had to keep pace. As his caustic commentaries made him notorious, he spent the rest of his life revising “that damned American language book.”

On into the 1940s, he added new chapters, new terms, even a “Declaration of Independence in American.” To wit:

WHEN THINGS get so balled up that the people of a country got to cut loose from some other country, and go it on their own hook, without asking no permission from nobody, excepting maybe God Almighty, then they ought to let everybody know why they done it, so that everybody can see they are not trying to put nothing over on nobody. . .

Mencken never lost his fascination with everyday speech, yet through a third and then a fourth revision, he told friends, “The book will kill me yet.”

In 1948, a stroke left Mencken unable to read or write. When he died eight years later, much of his commentary collected in six volumes seemed dated or mean. But The American Language remains fresh. Along with its celebration, he left us with advice. To honor the language called American, “listen to it on the street. It is there that it is alive.”