THE ATTIC READS. . . "THE PEOPLE'S TONGUE"

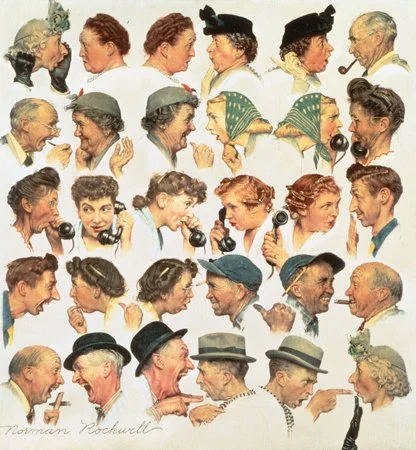

Classrooms have their dictionaries, speech has its grammarians, but American English belongs to all of us. To sample the language called American, put down that novel, that newspaper. Turn off the TV. “Listen to it on the street,” H.L. Mencken wrote in The American Language. “It is there that it is alive.”

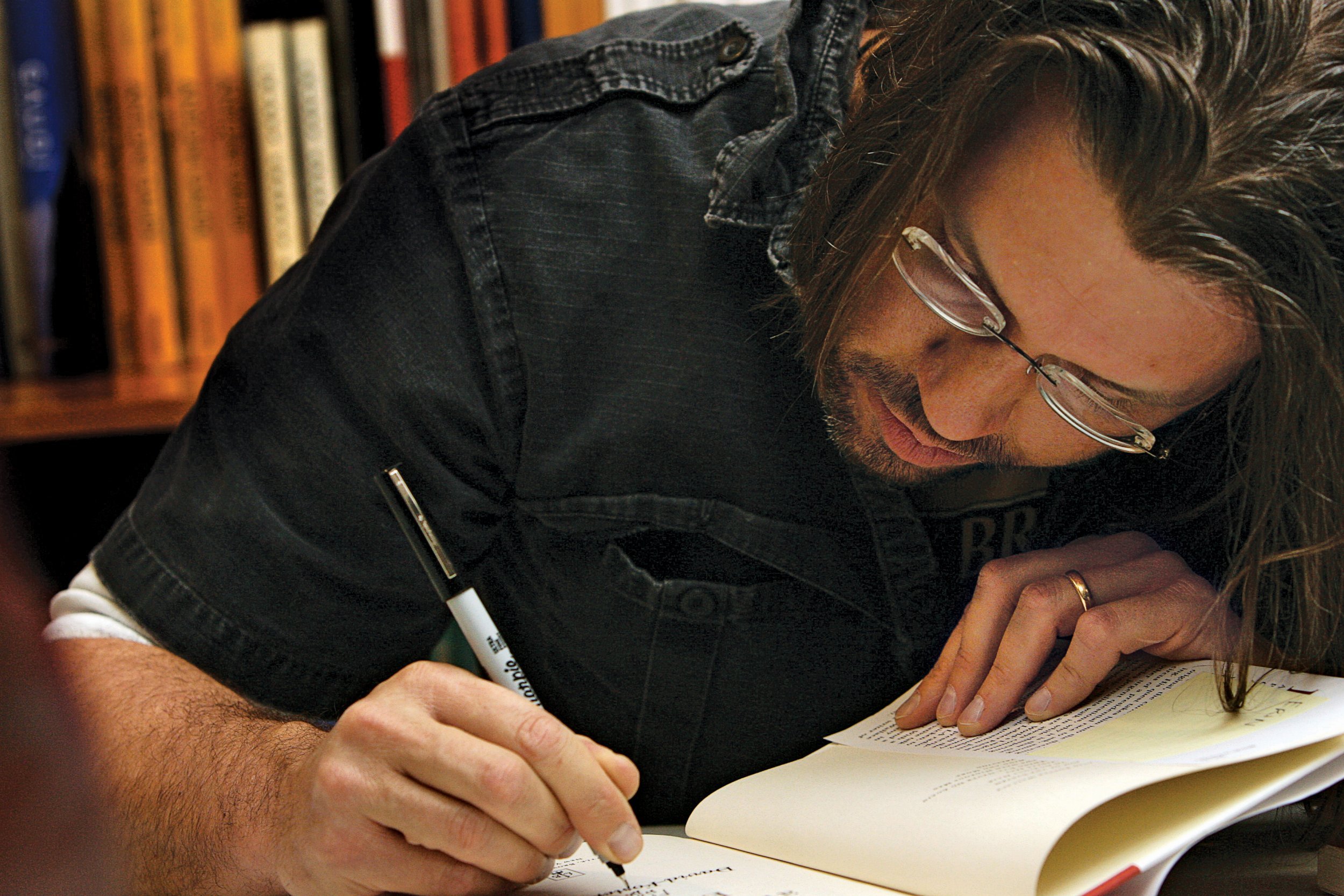

The People’s Tongue takes on the daunting task of illustrating our eccentric and free-flowing language and how it got so eccentric and free. But a linguist’s point of view might be dull, pedantic. That’s why veteran editor Ilan Stavans samples our twisted tongue along its winding journey from the Pilgrims to hip-hop, from Yiddish to Spanglish, from Amy Tan to David Foster Wallace.

Stavans’ delightful anthology tracks “the people’s tongue” across history, geography, literature, comedy, parody, blues, and beyond. Though the anthology is chronological, it’s more fun to hopscotch through its 73 entries. What better way to hear America talking than to jump from “Who’s on First” to “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall,” trip from Emily Dickinson to poet laureate Joy Harjo, stutter-step from “The Gettysburg Address” to “Green Eggs and Ham?” The anthology also offers sidetrips into serious analysis from Merriam-Webster, the Founding Fathers, and Stavans himself.

Stavans is the ideal editor for such a tongue trip. Raised in Mexico, author of an unfathomable number of books about English, Spanglish, and the immigrant experience, he studies and cherishes American English. “I myself am a lover of linguistic pollution,” he writes in his introduction. “I’m regularly in awe of the ingenuity of American English speakers.”

But too many, he knows, are not in awe of everyday English. Our language, like our history, is now a battleground. Changing faster than anyone can track, American English seems forever doomed to exaltation by purists and experimentation by those eager to toy with pronouns or claim exclusive rights to this or that term.

On those latter groups, the anthology’s best voice is Wallace. Politically Correct English (PCE) he writes, is “not just silly but confused and dangerous.” Dangerous because it ultimately backfires, benefitting the status quo. ”Were I, for instance, a political conservative who opposed taxation as a means of redistributing national wealth, I would be ndelighted to watch PCE progressives spend their time and energy arguing over whether a poor person should be described as ‘low-income’ or ‘economically disadvantaged’ or ‘pre-prosperous’ rather than constructing effective public arguments for redistributive legislation.”

Stavans acknowledges the ongoing Language Wars and is worried, slightly. “With the attention-span needle rapidly moving toward zero,” he writes, holding onto the basics of any language — consistent spelling and punctuation, words that mean what they used to mean and not what some pedant or politician wants them to — is problematic, though hardly impossible. Why be hopeful? “Because English loves to escape its confines, to enter alien territories, to lend and borrow words without restraint. Maybe because, while an elite is in command of government, the fluidity of the language has no keepers.”

Later entries in The People’s Tongue address our linguistic battles. A list of Trump’s Tweeted insults aimed at CNN runs to ten pages. Stavans himself defends “Spanglish,” and linguist John McWhorter states plainly that “English is a Living Language — Period.”

Reminding us just how alive American English remains is the point of The People’s Tongue. It belongs on your shelf, with Huckleberry Finn and Mencken and Ambrose Bierce’s The Devil’s Dictionary. American English, Stavans concludes, is forever changing, forever embattled, forever up for grabs. Yet it remains “of the people, by the people and for the people. It answers only to them.”