BANNEKER VS. JEFFERSON -- THE ALMANAC OF INEQUALITY

MONTICELLO, AUGUST 1791 — The Secretary of State is accustomed to mail from throughout the Western world. Each day brings correspondence from New York, Boston, Paris. . . But towards the end of another sweltering summer, Thomas Jefferson is surprised by a letter from Maryland.

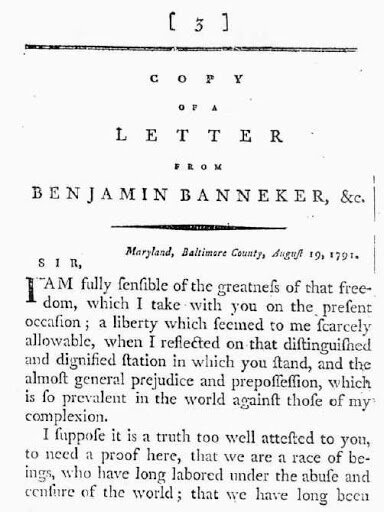

Sir,

I am fully sensible of the greatness of that freedom which I take with you on the present occasion; a liberty which Seemed to me scarcely allowable, when I reflected on that distinguished, and dignifyed station in which you Stand; and the almost general prejudice and prepossession which is so prevalent in the world against those of my complexion. . .

Complexion? Is this “articulate” correspondent a Negro? Jefferson reads on.

I suppose it is a truth too well attested to you, to need a proof here, that we are a race of Beings who have long laboured under the abuse and censure of the world, that we have long been looked upon with an eye of contempt, and that we have long been considered rather as brutish than human, and Scarcely capable of mental endowments.

Perhaps Jefferson turns the letter over, admiring the penmanship. Perhaps he skips to the signature. Benjamin Banneker. Never heard of him. But look. Astronomical tables. Sunrises. Tides and eclipses. Who is this man?

BANNEKER AND THE TIDE OF RACE

The son of a freed slave and a free black woman, Benjamin Banneker never felt slavery’s lash. But as a struggling tobacco farmer in Maryland, Banneker was keenly aware of his status. Every day brought discrimination, usually ugly, occasionally eloquent.

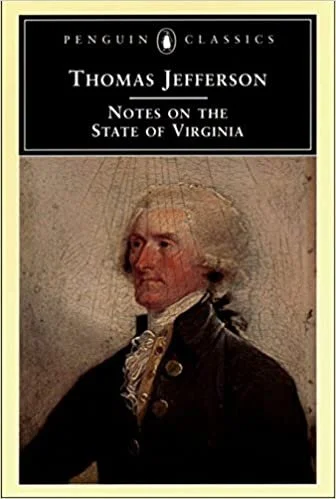

Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me that in memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior. . . Never yet have I found a black that had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration. . .

—- Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, 1785

By 1785, Banneker was managing a 100-acre farm, living in a log cabin, his hours chimed by a wooden clock he had made by hand. By candlelight, he pored over books lent by a Quaker friend, mastering the math needed to make ephemerides — astronomical tables vital to farmers and sailors.

Banneker planned to publish the tables in his own almanac, but first he mailed his hand-written manuscript to the author of the Declaration of Independence. Together with his letter, this was Benjamin Banneker’s Declaration. Jefferson read on. Summoning the spirit of 1776, Banneker recalled:

. . . a time in which you clearly saw into the injustice of a State of Slavery, and in which you had just apprehensions of the horrors of its condition, it was now Sir, that your abhorrence thereof was so excited, that you publickly held forth this true and invaluable doctrine, which is worthy to be recorded and remember’d in all Succeeding ages. “We hold these truths to be Self evident. . .”

How “pitiable,” Banneker continued, that fifteen years later, Jefferson should still be “detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren under groaning captivity and cruel oppression.”

JEFFERSON AND THE TIDE OF HISTORY

Only recently have historians openly condemned Jefferson’s views on slavery. Once dismissed as “conflicted,” they are now seen as the height of hypocrisy. Like other Founders, Jefferson held human beings in bondage. Unlike them, he fathered children with one slave, never freeing them even upon his death. Conflicted, hypocritical, Jefferson confessed his fears for a slave-holding America: “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever.”

Yet for one brief moment in the summer of 1791, Jefferson held a letter proving the immortal words from his Declaration and challenging his long-held prejudice. Jefferson might have burned the letter or ignored it. (He might even have changed his mind, but he later said he thought Banneker’s Quaker friend helped him do the math.) Nonetheless, Jefferson replied.

Sir,

I thank you sincerely for your letter of the 19th. instant and for the Almanac it contained. No body wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren, talents equal to those of the other colours of men, & that the appearance of a want of them is owing merely to the degraded condition of their existence. . .

Jefferson also sent Banneker’s Almanac to a Parisian friend and mathematician, the Marquis de Condorcet.

I am happy to be able to inform you that we have now in the United States a negro, the son of a black man born in Africa, and of a black woman born in the United States, who is a very respectable mathematician. . .

BANNEKER’S ALMANACS

The following summer, Banneker’s Almanac was published in several cities. For the next six years, annual editions sold well. Along with ephemerides, each almanac contained pleas for the abolition of slavery from leading politicians and pundits. Fledgling abolitionist societies used Banneker’s Almanac in arguing for equality of the races.

Benjamin Banneker died in his log cabin in 1806. An obituary noted: “Mr. Banneker is a prominent instance to prove that a descendant of Africa is susceptible of as great mental improvement and deep knowledge into the mysteries of nature as that of any other nation.”