JAIME ESCALANTE AND THE CALCULUS OF HOPE

AMERICA — 1983 — The report card was grim. Our schools were failing. “A rising tide of mediocrity” put “A Nation at Risk.” Marching to the rescue came the education experts, piling jargon high and deep. IEP. Hands on. Self-esteem. Meanwhile in an inner city classroom, one teacher had his own answer.

Ganas is Spanish for “desire,” but at Garfield High in East L.A., ganas came to mean drive and determination. “Ganas,” read a sign above the blackboard. “That is all I need.” And no teacher ever instilled more ganas than Jamie Escalante.

Escalante is a legend now, the subject of books and a movie and numerous awards. But behind the legend was the hard work. Raised in Bolivia by parents who were teachers, Escalante taught in La Paz for a dozen years before coming to California in 1963, seeking a better life for his wife and son.

ESCALANTE THE IMMIGRANT

He spoke no English, had just $3,000. Throughout the 1960s, Escalante worked as a janitor, a cook, and finally, after teaching himself English, as a technician. But his heart was in the classroom. Going to night school, he earned a credential, and at age 44, he took a 20 percent pay cut to teach at embattled Garfield High.

“My friends said, 'Jaime, you're crazy.' But I wanted to work with young people. That's more rewarding for me than the money."

Like many crusaders come to inner city schools, Escalante almost quit. Teaching remedial classes, he saw students struggle with math he’d mastered in fifth grade. There was no learning going on, just “baby-sitting.” After one final, Escalante was stunned by student scores. So he took the easy route, right? Blamed the students? Griped in the teacher’s room? Wrong again.

“I blew it, man,” he said. “I’m going to have to correct my mistakes.”

ESCALANTE IN THE CLASSROOM

He soon honed a classroom style students had never seen. Journalists drawn by his spreading story marveled. “He roamed the aisles, he juggled oranges, he dressed in costumes, he punched the air; he called you names, he called your Mom, he kicked you out, he lured you in; he danced, he boxed, he screamed, he whispered. He would do anything to get your attention.”

“Okay, who won the game last night?”

“The Dodgers!”

Pulling out a ball and a glove, Escalante got down to teaching. “As X approaches A, F of X is the trajectory. Could be a curve ball!”

Students called Escalante “Kimo,” short for the Lone Ranger as Tonto’s Kimo Sabe. He called them his burros. Mayans invented the zero, he said. “You burros have math in your blood.”

Along with ganas, Escalante’s surname suggested his mission. In Spanish, escalar means “to climb.”

ESCALANTE’S CHALLENGE

Four years into teaching, Escalante had a soaring idea. Just three percent of American students took the AP calculus exam. But math and technology were stairways to the future. Why shouldn’t students named Valdez and Estrella climb right alongside Miller and Adams?

Escalante taught Garfield’s first calculus class in 1978. Five students took the AP exam, and two passed. The next year, nine students took the exam. Seven passed. Then 14 the following year. And when, in 1982, 18 Garfield students passed AP calc, the story went nationwide.

Because the Educational Testing Service did not believe inner city students could do the math. Accusing them of cheating, the ETS nullified Garfield’s scores. Escalante was outraged. This would never happen to Miller and Adams. He convinced a dozen students to retake the exam. All passed.

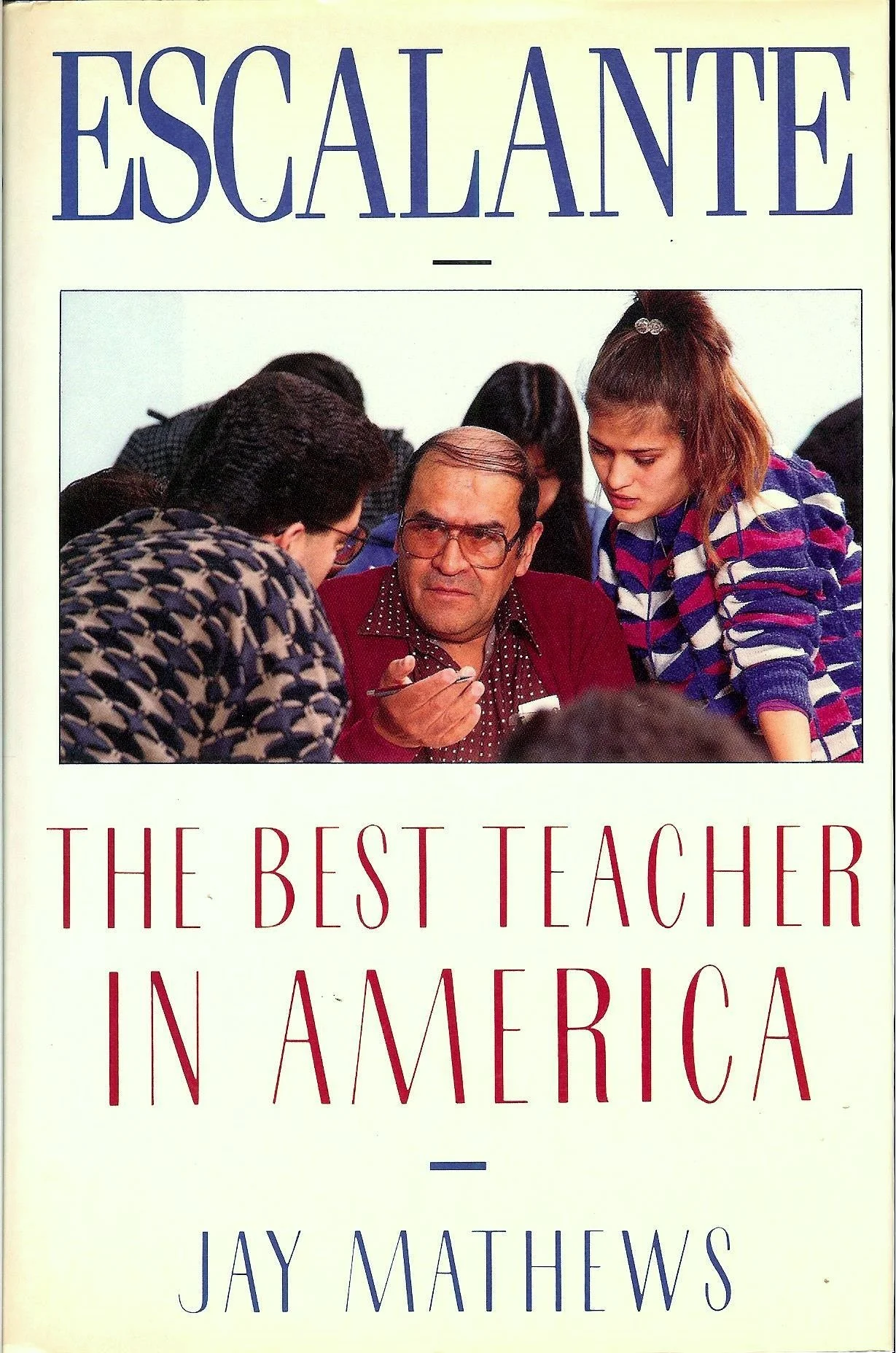

In 1983, the year of “A Nation at Risk,” 33 Garfield students passed AP calc. By 1987, the number was 75. A book spread his story — Escalante: The Best Teacher in America. Soon came the movie “Stand and Deliver.”

ESCALANTE — THE LEGEND

Edward James Olmos was nominated for an Oscar, but no actor could capture Escalante’s classroom charisma. “He's the most stylized man I've ever come across," Olmos said. "He had three basic personalities -- teacher, father-friend and street-gang equal -- and he would juggle them, shift in an instant. . . He's one of the greatest calculated entertainers."

Escalante’s fame soon alienated other teachers, new administrators. An invitation to the White House and classroom visits from celebrities didn’t help. Escalante left Garfield in 1992 and finished his career in Sacramento. In 2001, he moved back to Bolivia, but well-taught students do not forget.

Escalante’s burros went off to college and on to careers as technicians, programmers, engineers. . . Then in 2010, learning that Kimo had cancer, they reunited. Alerted by Olmos, students gathered at Garfield High for fund-raisers that paid Escalante’s medical bills. When Escalante died that year, tributes poured out.

“All these years he’s never been out of my mind,” said Jema Estrella, an architect in L.A. “His presence was always felt.”

Sergio Valdez, a mechanical engineer at Pasadena’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, agreed. “Everything I’ve done, I owe to him.”

Escalante always insisted his only secret was hard work — by both students and teachers. But ganas played its part, plus a little esperanza.

“Believe, believe,” he often said. “Believe in your kids. They will surprise you.”