THE WOMAN WHO 'GOT' VIETNAM

HUE, SOUTH VIETNAM — 1966 — A year after the first Marines landed, Americans solidly supported the war. Newspapers and TV dutifully reported battles, body counts, and generals’ upbeat assessments. “We are not only going to win, we are winning.”

Then on a muggy March afternoon, an army helicopter touched down in Hue. Ducking beneath the chop-chop of whirling blades, reporters met sergeants and staff, shook hands, slapped backs. But the last person to step out of the helicopter stopped the troops cold.

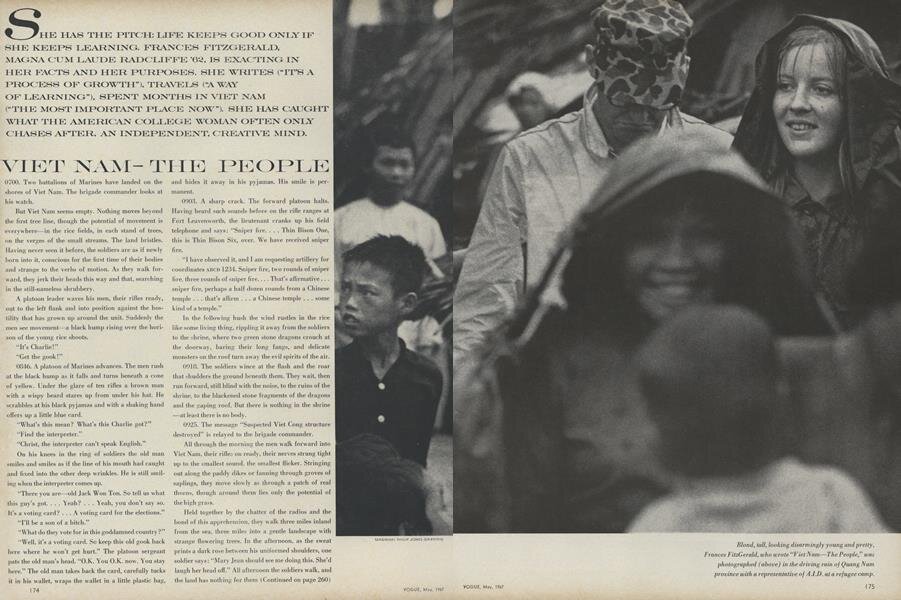

Dressed in army fatigues, she was a woman, tall and striking. Soldiers instantly surrounded her, steering her away from the waiting jeep. She explained that she was a reporter, too. Not for the Post, the Times, or Newsweek. She was a freelancer, first time “in country.” Her name was Frankie.

At 25, Frances FitzGerald had led a Camelot life. Her father was a Wall Street lawyer, her mother a Massachusetts Peabody, brother of the governor, and appointed by JFK to a U.N. post. Frances grew up with country clubs, debutante balls, limousines. But in January 1966, she turned her back on all that, and on the “pink ghetto” of women’s journalism, and paid her way to Vietnam.

She expected to stay a month. She had no assignments, no idea what she would write about. But she soon saw what was later called the “bright, shining lie.”

“Vietnam hit FitzGerald like a thunderbolt,” wrote Elizabeth Becker in You Don’t Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War. “She found the whole war unbelievable. It challenged her understanding of how the world worked.”

Just as Vietnam changed FitzGerald, she changed American understanding of the war. From her first article in the Village Voice, FitzGerald saw Vietnam through a different lens. Some reporters saw the war as a Cold War proxy. Others envisioned Audie Murphy on an Asian stage. But FitzGerald saw two vastly different cultures doomed to misunderstanding and destruction.

Once in country, FitzGerald talked to people other reporters avoided. Villagers. Monks. Peasants. Speaking fluent French, she read a history of the French in Vietnam, written by a historian raised near Hanoi. Her father, who had become a C.I.A. Deputy Director, told her she was “all wet,” but she pressed on.

“You must not forget,” she wrote to herself, “you simply must not forget that this war is a tragedy.”

Extending her visit, FitzGerald pounded out articles on the typewriter she had packed in her lone suitcase. By November, when she returned to the U.S., she had written for the Voice, the New York Times, the Atlantic, and had material for future articles.

“She was looking at things in a completely different optic,” recalled Washington Post correspondent Ward Just. “Like she was from a different country — a whole new meaning to the phrase ‘foreign correspondent.’”

Home from Vietnam, FitzGerald began a book. For three years, while the tragedy ground on, she contrasted the warring cultures. Other reporters studied battle plans, but FitzGerald studied Vietnamese history. A thousand year struggle to expel the Chinese, then the French, made Americans just the latest invaders. A culture based on Buddhism and Confucianism had little use for Americanization. In their understanding of politics, economics, truth, even time, America and Vietnam were polar opposites.

One people, she wrote, saw the war on television, where “the cries of the wounded become the background accompaniment for dinner. For the other people, the war would come one day out of a clear blue sky. In a few minutes it would be over: the bombs released by an invisible pilot with incomprehensible intentions. . . Which people was best equipped to fight the war?”

Serialized in The New Yorker, then published in 1972, Fire in the Lake was FitzGerald’s answer. The war was unwinnable. No matter how long the suffering went on, Vietnam would ultimately reject America “as an organism rejects a foreign body.”

Blending history, culture, and religion with solid reporting, Fire in the Lake became a huge best-seller. “If Americans read only one book to understand what we have done to the Vietnamese and to ourselves,” historian Arthur Schlesinger wrote, “let it be this one.”

Fire in the Lake won the Pulitzer, the National Book Award, and the Bancroft Prize for History. FitzGerald moved on to write widely read books on American history texts, Reagan’s Star Wars, utopian communities and more. Her most recent book studies American evangelicals with the same detached detail she applied to Vietnam.

When she first arrived in Saigon, a military liaison told “Frankie,” “This is not your world.” But she made it hers, and ours, firing a warning shot that still resounds.