THE MAN ON THE FLYING CARPET

AMERICA 1920s— When the roaring began, not everyone roared along. For every flapper, hundreds were housebound. For every Hemingway hero, thousands were chained to jobs. But in the spring of 1921, a young Princeton student hit the road and took America along for the fun.

“I flung my book away and rushed out of the apartment on to the throbbing shadowy campus. The lake in the valley, I knew, would be glittering, and I turned toward it, surging within at the sense of temporary escape from confinement. Cool and clean, the wind, frolicking down the aisle of trees, tousled my hair, and set my blood to dancing. . .”

Richard Halliburton lived the other American Dream — adventure. Disdainful of the settled life, the “even tenor,” Halliburton was at play in the world, the entire world.

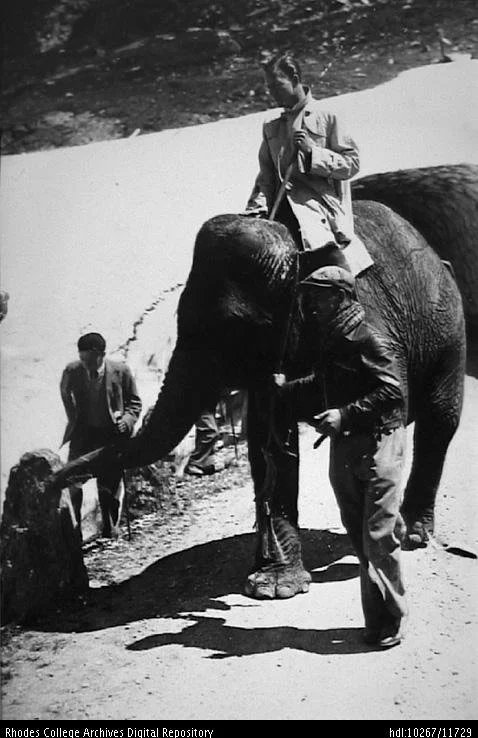

Between the world wars, Halliburton was always in the news, always on the run. Though just 5’7,” 140 pounds, he swam the length of the Panama Canal and the Grand Canal in Venice. He climbed the Matterhorn and Mount Fuji. He slept atop the Great Pyramid of Cheops. He crossed the Alps on an elephant. . .

Halliburton’s road romance began in the usual place — boyhood. Raised in Tennessee, he fell in love with geography and the world’s wonders. His dreams were amped up in bed where a heart murmur confined him for months. After he recovered his brother died of rheumatic fever. Being gay in a tightly closeted time must have also heightened his restlessness, his risk-taking. So by the time he entered Princeton, Halliburton knew how fragile life was and how fleeting.

“Let those who wish have their respectability,” he wrote. “I wanted freedom, freedom to indulge in whatever caprice struck my fancy, freedom to search in the farthermost corners of the earth for the beautiful, the joyous and the romantic.”

A gap year trip to Europe planted seeds of wanderlust. Bursting out of college, Halliburton began to travel, write, and lecture. Though he was no prose stylist like his classmate F. Scott Fitzgerald, at a podium he lifted audiences to the stars.

“There probably is no human being in the world who can talk with the energy of Mr. Halliburton,” a newspaper noted. “He simply throws ‘er in high gear, opens wide the throttle and lets go.”

In 1925, The Royal Road to Romance recounted Halliburton’s early adventures and became a best-seller. For his next magic trick, he began re-tracing famous odysseys, starting with Odysseus’ wanderings through the Mediterranean. The Glorious Adventure (1927) led to New Worlds to Conquer which recounted his Panama Canal swim and his journey in the footsteps Cortez. Next stop — the globe.

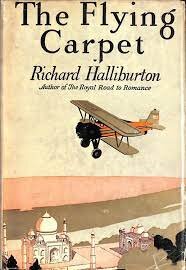

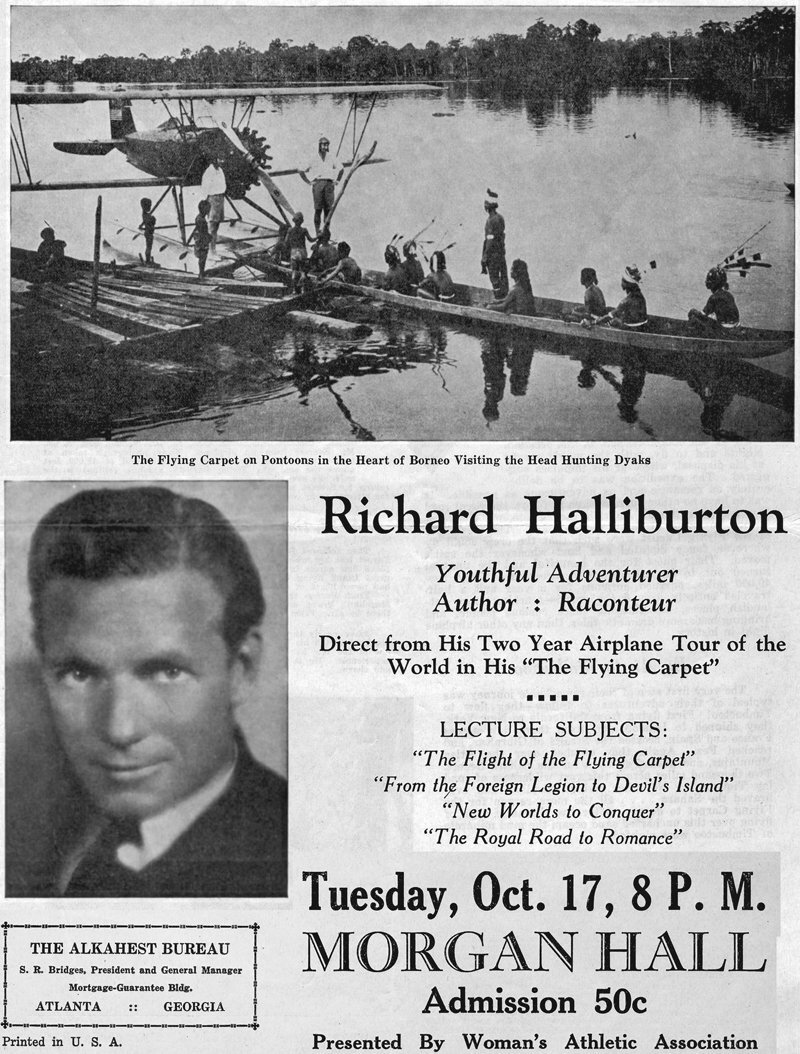

As America sank into the Depression, Halliburton found a pilot who shared his dreams. With just a handshake, he booked a rear seat on a biplane he named “The Flying Carpet.” Watching the plane take off from L.A., Halliburton’s father wrote: “For the first time I realize that you no longer belong to your mother and me. You now belong to your readers, your vast audience—you belong to the world.”

Just three years after Lindbergh, Halliburton expanded America’s sense of wonder. After landing on Long Island, he shipped his plane to England where the adventure began. South to Paris and on to Gibraltar. A stop in Morocco, then across its Atlas Mountains to Timbuktu, the first plane to land there. Back north to Algeria where Halliburton hobnobbed with the French Foreign Legion. Then Cairo, Damascus, Petra and on to the Taj Mahal where Halliburton snuck past guards for a moonlight swim in a reflecting pool.

Then up, up into the Himalayas where Halliburton stood up in the cockpit to take the first aerial photo of Everest. And on. And on. 33,000 miles, 34 countries, at a huge personal expense which Halliburton recovered with interest when The Flying Carpet made him a household name and fired up a new generation of dreamers.

Walter Cronkite said Halliburton inspired him to become a reporter. Susan Sontag, reading Halliburton’s Book of Marvels, saw “my first vision of what I thought had to be the most privileged of lives, that of a writer.”

But there was always one more adventure. And one last one.

In 1938, Halliburton dreamed of sailing a Chinese junk from Hong Kong to San Francisco. Unable to find a suitable ship, he had one built. The Sea Dragon was top heavy, reeling and rolling, but Halliburton saw it as “a poetry-ship devoid of weight and substance, gliding with bright-hued sails across a silver ocean to a magic land.”

Days out of Hong Kong, the Sea Dragon sailed into a typhoon. Hellacious winds and fifty foot waves ended Halliburton’s last adventure. Like Amelia Earhart two years earlier, Richard Halliburton vanished into time and legend.

Halliburton’s death surprised no one. Vanity Fair had already nominated him “for oblivion.” Halliburton, too, knew his days were numbered. But back at Princeton, when his father urged him to take “an even tenor,” he wrote:

“I hate that expression, and as far as I am able I intend to avoid that condition. . . And when my time comes to die, I'll be able to die happy, for I will have done and seen and heard and experienced all the joy, pain and thrills—any emotion that any human ever had.”