ELLA BAKER -- HOW TO GROW A MOVEMENT

GREENSBORO, NC, FEB 1960 — Four black men sat at the all-white lunch counter, refusing to move until served. When Woolworth’s closed, they left, then returned the next day with a dozen friends. Within a week, “sit-ins” started in Atlanta, Nashville, Durham, Raleigh. . . The Movement was galvanized. But one woman knew that freedom meant “more than a hamburger.”

The common take on the Civil Rights movement is simplistic. Julian Bond, present at the creation, summed it up: “Rosa sat down, Martin stood up, and then the white folks saw the light and saved the day." But with all due respect to Rosa and Martin, there would have been no Civil Rights Bill, no Voting Rights Act, no deep movement at all without Ella.

“You didn't see me on television,” Ella Baker said “You didn't see news stories about me. The kind of role that I tried to play was to pick up pieces or put together pieces out of which I hoped organization might come. My theory is, strong people don't need strong leaders.”

Ella Baker grew up in North Carolina, listening to stories of strong people. People like her grandmother, born a slave, beaten, whipped, for refusing to marry the man chosen by her master. Smart and driven, Baker learned the power that rests in ordinary folks.

“Oppressed people, whatever their level of formal education, have the ability to understand and interpret the world around them,” Baker said, “to see the world for what it is and move to transform it.”

After graduating from Shaw University, Baker spent a dozen years organizing in New York. In 1940, she joined the NAACP, but she chafed at its ego-centrism and “go slow” approach based on lawsuits and lobbying. So she hit the road.

For several years, Baker roamed the South, meeting, recruiting, learning. She sat at rickety tables, slept in shotgun shacks, and probed the souls of black folk. So when Rosa sat down, Ella was ready to rise up. But first she had to deal with Martin.

“Martin wasn't good at receiving critical questions,” Baker recalled. “He was not alone; this was a pattern with ministers. After all, who was I? I was female; I was old. I didn't have any Ph.D.“

Ella helped Martin form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, yet she recoiled at its “top down” approach. Instead of a leader-centered group, she favored “group-centered leadership.”

On Easter weekend in 1960, as sit-ins continued across the South, Ella convinced Martin to fund a conference at Shaw University. Some 150 students came from a dozen states. King addressed the group but students rallied around the Reverend James Lawson, preaching that “love is the central motif of nonviolence.”

Then Ella spoke. Students deserved to lead themselves, she said. And their goal should be “more than a hamburger.”

“She didn't say, 'Don't let Martin Luther King tell you what to do,'" Julian Bond remembered, "but you got the real feeling that that's what she meant." With Ella as its “godmother,” students formed the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. SNCC (pronounced “snick”) became the “shock troops” of the Civil Rights movement.

When violence stalled CORE’s daring Freedom Rides, SNCC members came to Birmingham, defied mobs, boarded buses, and rode on. SNCC’s spirit — “Jail, no bail” and “One Man, One Vote” — drew the best and bravest to its “beloved community.”

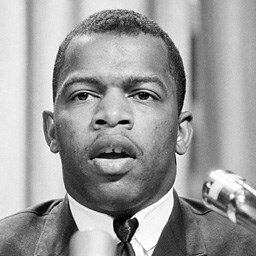

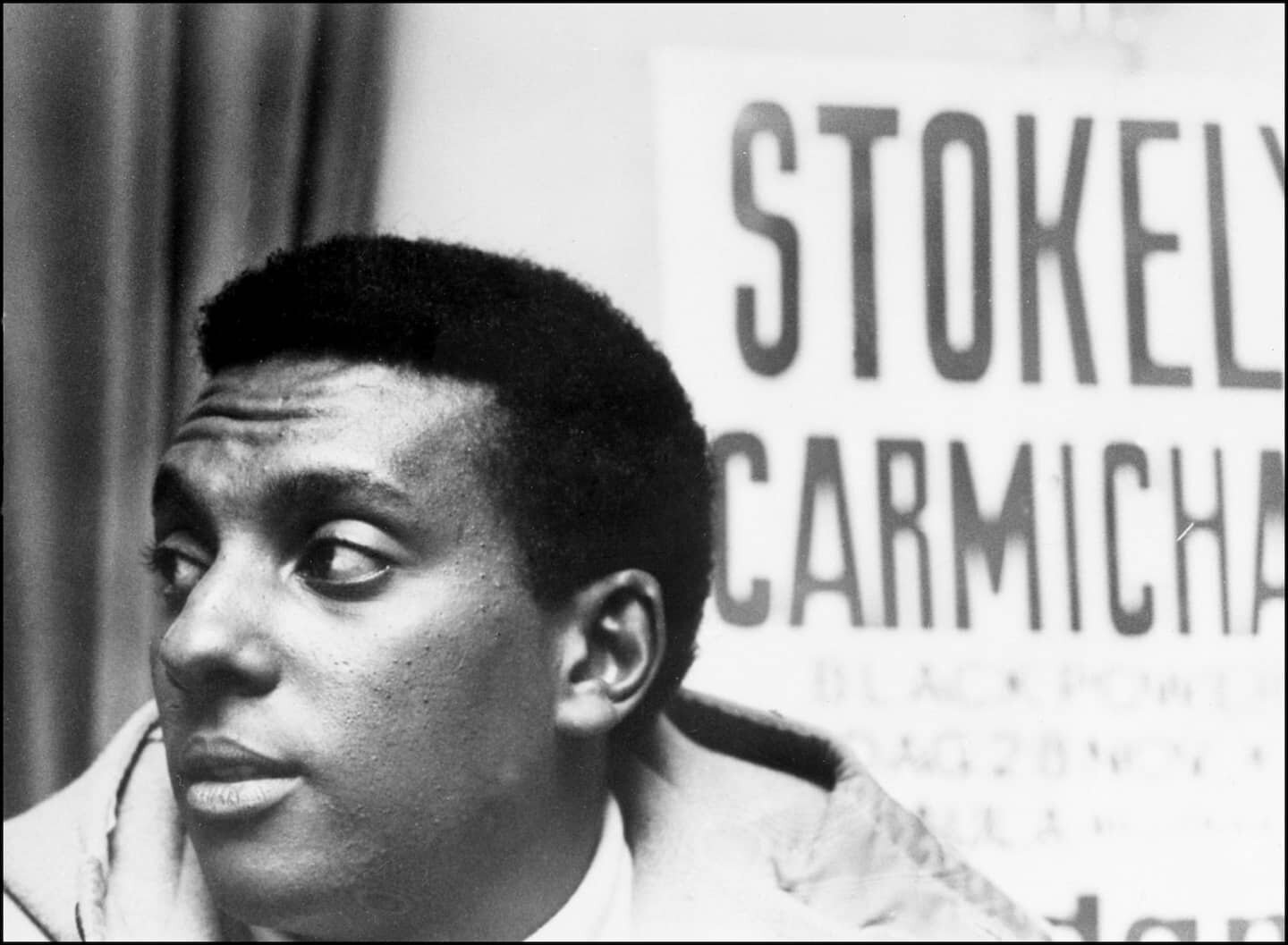

SCLC had King, but SNCC had John Lewis. Bob Moses. Stokely Carmichael. Diane Nash. And behind the scenes, SNCC had Ella Baker.

“I could count on Ms. Baker to be truthful,” Nash remembered. “She explained many things to me very honestly. I would leave her feeling very emotionally picked up, dusted off and ready to go.”

SNCC’s “participatory democracy” allowed all members to speak in meetings that often lasted all night. SNCC’s were fiery, feisty. “They would argue with a fence post,” one member recalled. But when SNCC “moved on Mississippi,” and on rural Georgia and Alabama, local people did more than listen. They took responsibility for their lives, going to the courthouse to register, organizing neighborhoods, learning how power worked.

It was SNCC that pulled off Freedom Summer, SNCC that challenged the Democratic National Convention that year, and SNCC that sought “Black Power.” By then, Baker and many founders were exhausted. Some left but Ella moved on, forming new organizations, earning the nickname Fundi, Swahili for an elder who teaches a craft to a new generation.

Ella Baker died in 1986 on her 83rd birthday. Four years later, “Eyes on the Prize” introduced “the Godmother of SNCC” to a larger audience. By then, however, the grassroots had grown — into registered voters, community organizers, Freedom School students teaching their own.

"Remember,” Ella often reminded SNCC, “we are not fighting for the freedom of the Negro alone, but for the freedom of the human spirit, a larger freedom that encompasses all mankind."