"LUCKIEST MAN" -- THE GRACE OF LOU GEHRIG

YANKEE STADIUM, JULY 4, 1939 — Throughout this cathedral of baseball, patriotic bunting suggests a World Series, but it’s just a routine doubleheader. Until the first game ends and the crowd stirs.

Dignitaries and former players fill the infield. Mayor LaGuardia speaks, then Babe Ruth. But the crowd chants “We want Lou! We want Lou!” Wiping away tears, Gehrig begins. “For the past two weeks you’ve been reading about a bad break. . .”

Ballplayers in 1939 were scrappy sons of miners, sons of dock workers. They played hard, drank hard, chased women, spit tobacco. But in Lou Gehrig, Americans saw what baseball could be — a classy credit to the country.

America knows Gehrig for the bad break that bears his name. Amyotropic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, is still called “Lou Gehrig’s disease.” But ALS was little-known until it struck baseball’s great gentleman.

Growing up in a rough and tumble America, Gehrig bore its scars. His parents, German immigrants, struggled to raise four children, then three, then two. . . After a third sibling died in infancy, Lou was left an only child, raised by a strong-willed mother.

“If it had not been for my mother, well, I’d be a good-natured, strong-armed and strong-backed boy pushing a truck around New York.”

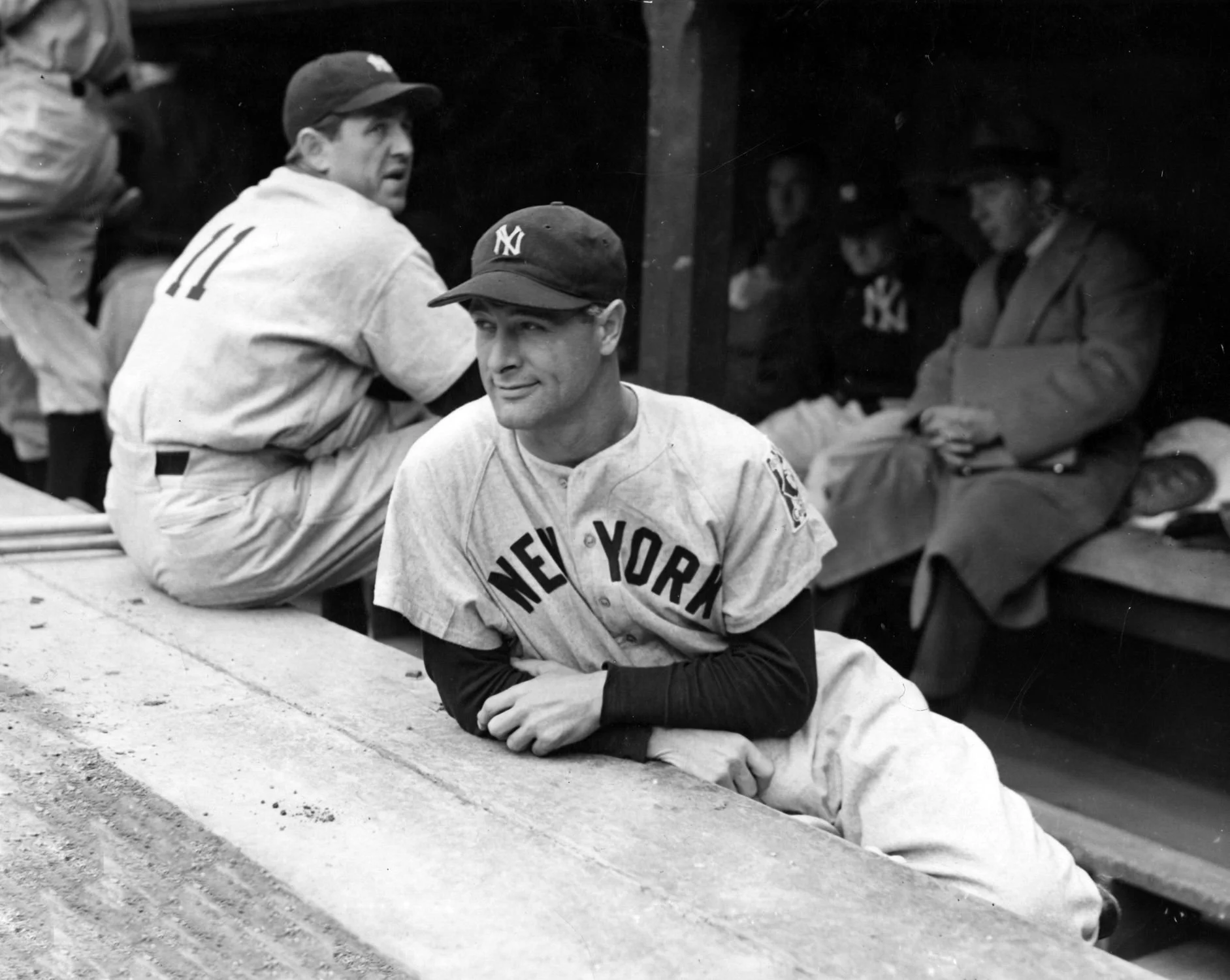

But Lou seemed born to play ball. Fourteen pounds at birth, he grew into a strapping 6’1”, 210, yet too shy to shine until the first pitch. High school stardom earned him a scholarship to Columbia where a Yankee scout saw “the next Babe Ruth.” Gehrig went straight from Columbia to Yankee Stadium and in 1925, won the starting first base job.

Through the next 14 seasons, “The Iron Horse” never missed a single game. His record — 2,130 consecutive games — stood for decades but he did more than show up. In 1927, when Ruth hit 60 homers, Gehrig hit 47, more than half the other teams in the league. Batting.373, driving in a record 184 runs, Gehrig, not Ruth, won the MVP. Gehrig went on to hit nearly 500 homers and land in the top ten of every slugging stat. But he also stood out off the field.

In an age when players drank till curfew, then slipped booze and women into hotel rooms, Gehrig preferred to go to the movies. During homestands and spring training he lived with his mother. Christina Gehrig still spoke German with her son, and carefully screened the few women he met.

”He was just hopeless,” one Yankee said. “When a woman would ask him for an autograph, he would be absolutely paralyzed with embarrassment.”

On into the 1930s, Ruth got the headlines but Gehrig didn’t mind. “There’ll never be another guy like the Babe,” he said. “I get more kick out of seeing him hit one than I do from hitting one myself.”

Then in 1939, the bad break. During spring training, Gehrig dropped pop flies, muffed grounders. “He didn’t have a shred of his former power or his timing,” Joe DiMaggio remembered. All players age but this, one sportswriter recalled, “was like a match burning out.”

Gehrig struggled on, hitting.143, until the day he told his manager, "I'm benching myself, Joe, for the good of the team.” Local doctors found nothing, so Gehrig went to the Mayo Clinic.

“The diagnosis was not difficult,” Dr. Harold Habein recalled. “There was some wasting of the muscles of his left hand as well as the right. . . “

ALS withers muscles into flimsy cords. Even in an “Iron Horse,” the disease is devastating. Gehrig softened the news for his wife. After a shy and awkward courtship, they had been married just six years. “There isn’t any cure,” he wrote Eleanor. “The best they can hope is to check it at the point it is now and there is a 50-50 chance for that. . . I may need a cane in 10 to 15 years. Playing is out of the question.”

Gehrig tried to hide his bad break but the story leaked. Two years earlier the Sporting News called him “the perennial youth of the game.” Now he could barely walk. Sportswriters demanded a Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day.

By noon, Yankee Stadium was full — 61,000 fans. Gehrig was terrified, saying “I’d give a month’s pay to get out of this.” Stepping to the plate, he kept his head down, careful not to stumble. Asked to speak, he shook his head. But fans kept chanting. Finally. . .

With nothing prepared, Gehrig spoke from the heart. Bad break? “Today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.” When the applause died, he continued. “Privileged” to play with legendary players, “lucky” to have parents who worked “all their lives so that you can have an education . . .” And his wife “a tower of strength. . .” He even credited “the groundskeepers and office staff.”

Gehrig took a deep breath. “So I close in saying that I might have had a bad break, but I have an awful lot to live for. Thank you.”

ALS does its damage with differing speeds. Stephen Hawking lived on for decades. Others, like my friend Bruce Marbin, last for just a few. Lou Gehrig died in 1941. He was 38. He left behind records that in 1999 earned him the most votes of any player on the Team of the Century.

But for all his athletic prowess, his legacy comes from that July 4. When he stood at the plate, cap in hand, clinging to life, summoning more courage and class than the game has seen before or since. In that moment, Lou Gehrig made Americans the luckiest fans.