THE FALL OF 'THE GREAT WHITE HOPE'

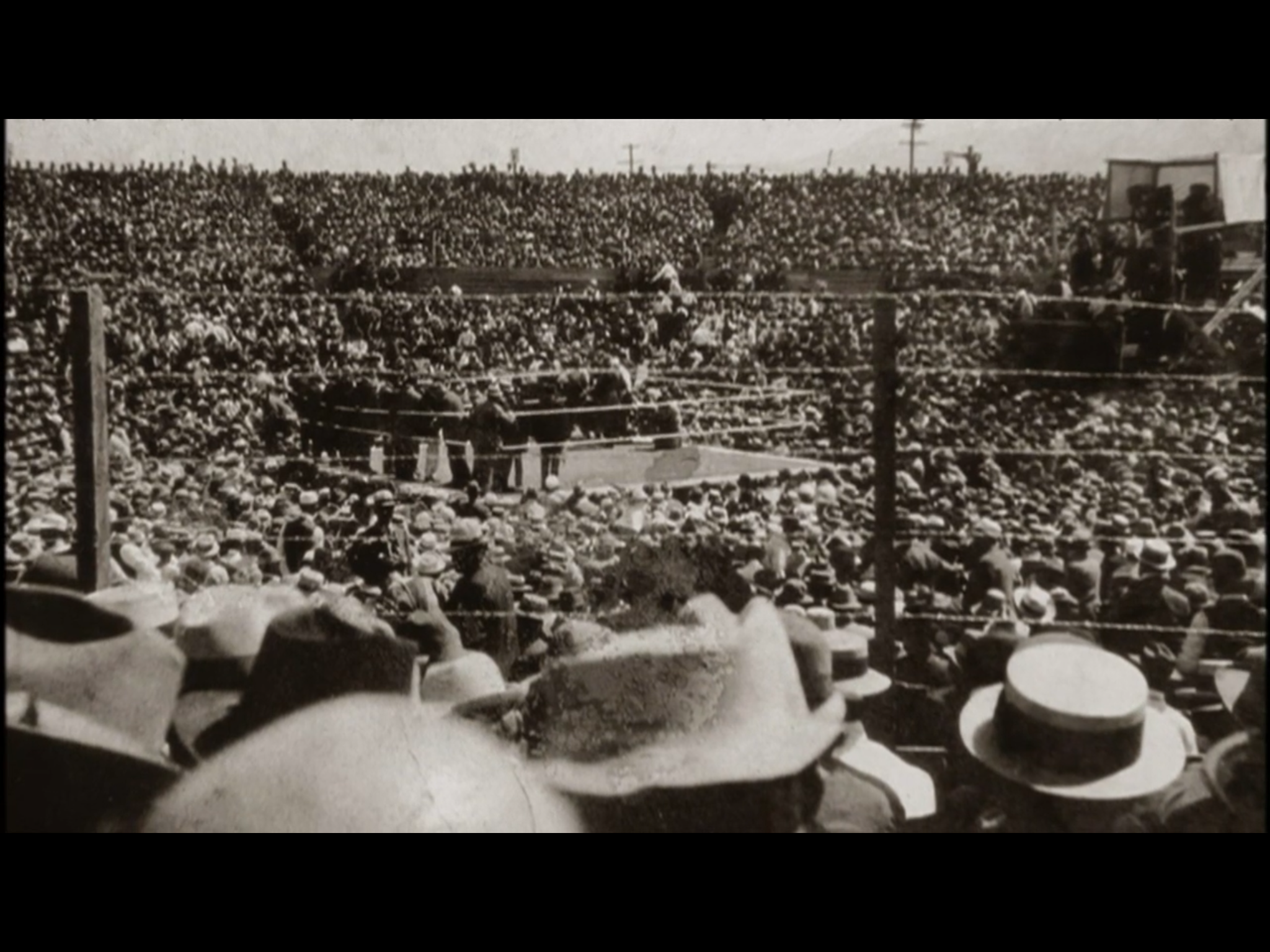

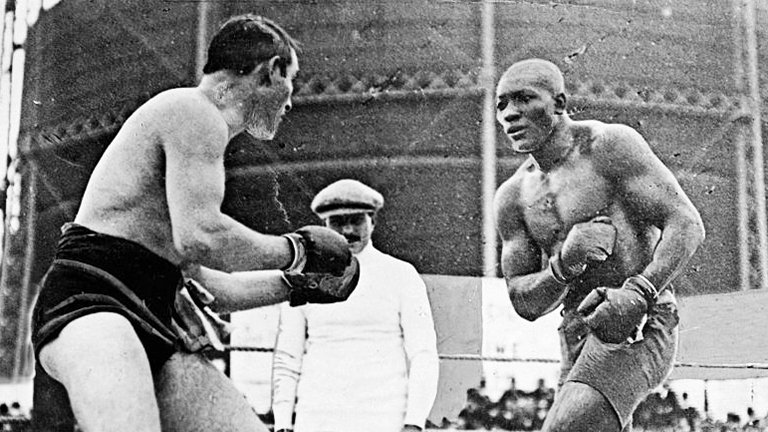

RENO, NV — JULY 4, 1910 — On the outskirts of this gambling town, 20,000 people cram into creaky wooden stands. Thousands more mill outside. The heat is scorching, the mood hotter. The Great White Hope has come!

At 2:30 p.m., two hulking boxers enter the ring, one white, one black. When the bell rings to start the fight, much more than a boxing title is at stake.

1900-1910: American race relations hit bottom. Jim Crow locks down the South. Sharecroppers live in tarpaper shacks. Race riots — whites beating blacks — rage in several cities. Dozens are lynched each year. And from “The White Man’s Burden” to books such as The Negro: A Beast, whites preach their supremacy.

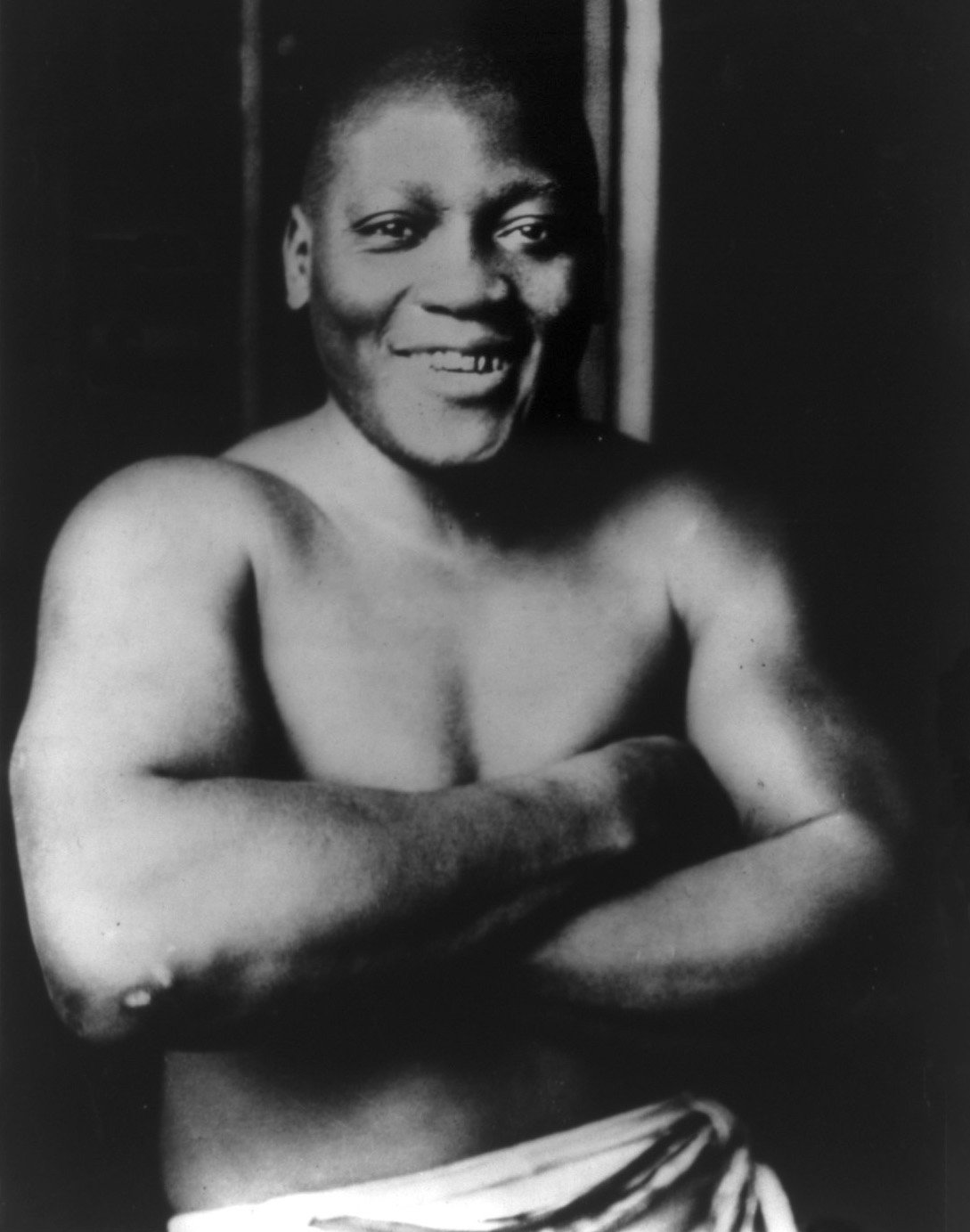

And then. . . Jack Johnson

From a hardscrabble Texas childhood, Johnson rose through the boxing world. Massive and muscular, Johnson learned to box behind bars. Back in 1901, inter-racial boxing was illegal, landing Johnson and an opponent in a Texas jail. Sharing a cell, the veteran white fighter taught Johnson how to box. Finally freed, Johnson set his sights on the heavyweight crown.

Yet heavyweight boxing, like baseball, was all white. How would America handle a black heavyweight? By ignoring him. But who could ignore Jack Johnson?

“I found no better way of avoiding race prejudice,” Johnson said, “than to act with people of other races as if prejudice did not exist.” Johnson drove fancy cars, dressed fine, spent lavishly. He behaved, said W.E.B. DuBois, with “unforgivable blackness.” Most unforgivable was Johnson’s cavorting with white women. America seethed.

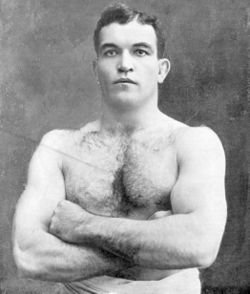

By 1903, Johnson was, one newspaper wrote, “the only logical candidate” for the heavyweight crown. But champion Jim Jeffries declared “I will never fight a Negro.” Then in 1905, Jeffries retired.

While running his alfalfa farm near L.A., Jeffries refereed a title bout. The new champion, Tommy Burns, also refused to fight Johnson, saying “all coons are yellow.” But under pressure, Burns finally agreed to fight for a purse of $30,000.

Burns thought the huge sum would end all talk, but an Australian promoter put up the money. “The first great battle of an inevitable race war,” one paper proclaimed, was on. In December 1908, in a stadium outside Sydney, a cheering, all-white crowd bet on Burns.

At the opening bell, Johnson strode out of his corner. “Here I am, Tommy. Who told you I was yellow?” Johnson’s first blow staggered Burns. A second knocked him down. When Burns rose, Johnson pointed to his stomach. “Hit me here, Tommy,” he said, then took the blow with ease. “Poor little Tommy. Who told you you were a fighter?”

Covering the fight, novelist Jack London called it “a hopeless massacre.” Police stopped the massacre in the fourteenth round, making Johnson the champ. White America was frantic.

For the next two years, as America searched for a “Great White Hope,” Johnson destroyed one challenger after another. “One thing remains,” London wrote. “Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove that smile from Johnson’s face. Jeff, it’s up to you.”

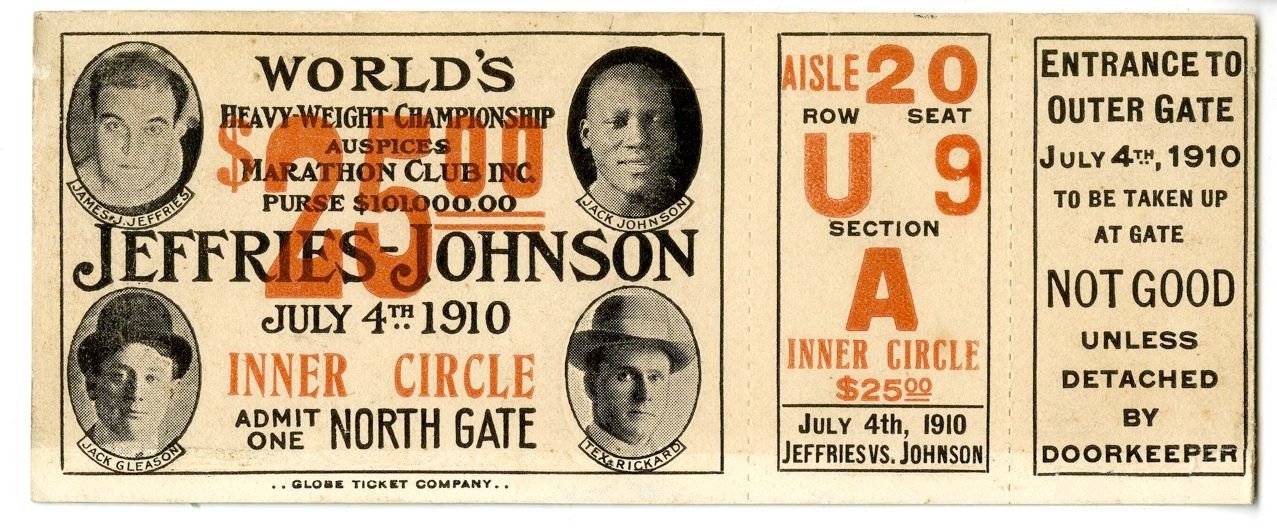

Jeffries had gained 100 pounds, yet “they kept at me,” he said, “even in churches they were sermonizing that I was a skunk for not defending the white man’s honor.” Finally, Jeffries agreed. The fight was set for July 4, 1910, in Reno (pop. 10,467).

In training, Jeffries assured America, “I want to see the championship come back to the white race, where it belongs.” Johnson just smiled. As the fight approached, a British magazine summed up the stakes.

White supremacy was based on the “fact” of black inferiority. Yet “here we are, the hitherto dominant race, compelled to recognize that an American Negro, the descendant of an emancipated slave, is our acknowledged master of the one great physical sport in which actual personal superiority can ever be authoritatively tested.” Jeffries simply had to beat Johnson. Had to.

By the Fourth, America was on a hair-trigger. Crowds surrounded big city telegraph offices. Thirty thousand filled Times Square to read the blow-by-blow on bulletin boards. Reno overflowed with fans shouting, waving straw boaters, betting on Jeffries.

Beneath a blistering sun, fans chanted for the fight to begin. Finally, at 2:30 p.m., the fighters entered. Boos and racial slurs rained down on Johnson. He just smiled. Jeffries, grim-faced, drew an enormous ovation. Johnson offered to shake Jeffries’ hand. Jeffries refused. The men retired to their corners. The bell rang.

For three rounds, Jeffries pounded Johnson’s midsection. Johnson parried the blows. “Come on now, Mr. Jeff,” Johnson shouted. “Let me see what you got. Do something, man. This is for the championship!” In the fourth round, Jeffries opened a cut on Johnson’s mouth. A telegraph wired: “First blood for Jeff!” Times Square crowds cheered.

In the fifth, Johnson took\ command. The rest of the fight, Jack London wrote, is “all Johnson.” By the eighth, Johnson was toying with Jeffries. Clinching the huge boxer, walking him to his corner, Johnson asked Jeffries’ trainer, “Where do you want me to put him, Mr. Corbett?”

By the fourteenth round, Jeffries’ nose was broken. Blood spattered his legs and chest. Jeffries had never been knocked down, but Johnson floored him with one blow. Jeffries got up. Johnson decked him again.

When Johnson was declared winner, trainers hurried to protect him from whites rushing the ring. Johnson slipped past and offered his hand to Jeffries. Jeffries refused it. Jeffries later admitted, “I could never have whipped Jack Johnson at my best. I couldn’t have reached him in a thousand years.”

That night, across America, whites and blacks fought in the streets. Dozens died. One black professor weighed the toll: “It was a good deal better for Johnson to win and a few Negroes be killed in body for it than for Johnson to have lost and all Negros be killed in spirit from the preachments of inferiority.”

Jim Crow remained in power, but a black man was the undisputed heavyweight champion. “Unforgivable blackness” had triumphed.