WHERE THE FUTURE STUDIED

BLACK MOUNTAIN, NC, SUMMER 1933 — In the foothills of the Smoky Mountains, just months after FDR promised “a New Deal for the American people,” a gaggle of disgruntled professors started a new college.

Prospects for Black Mountain College were not good. Unemployment was 25 percent. Bread lines and hobo camps dotted the American landscape. In higher education, art and music were afterthoughts, well down the food chain from business, econ, and the humanities core of Latin, English, and (gag!) American history.

But classics scholar John Andrew Rice and his fellow founders were fed up with academia. Recently dismissed — or resigned in disgust — from a small college in Florida, they decided this new college would be, well. . . different. There would be no pomp, just circumstance — circumstance that led to students “being something” not just “getting something.”

After a summer of scrambling to find a campus, faculty, students, and subsistence funding, Black Mountain College opened that fall. The college lasted just 24 years, yet we are still talking about it, about its spirit, its freedom, and the revolutionary art, music, dance, and poetry it jumpstarted.

Becoming “a kind of Shangri-La for avant-garde art,” Black Mountain struggled through the Depression, nurturing eccentricity, innovation, and hope. By the late 1940s, the college was an incubator of genius.

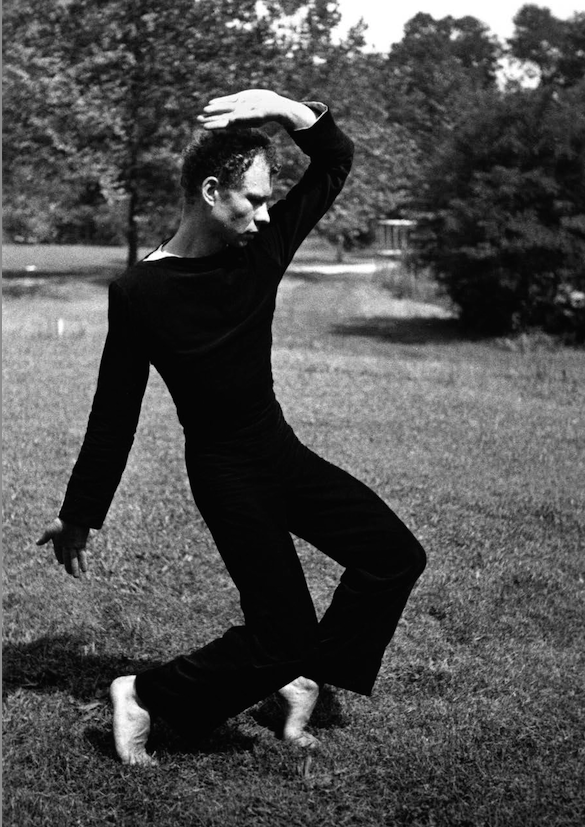

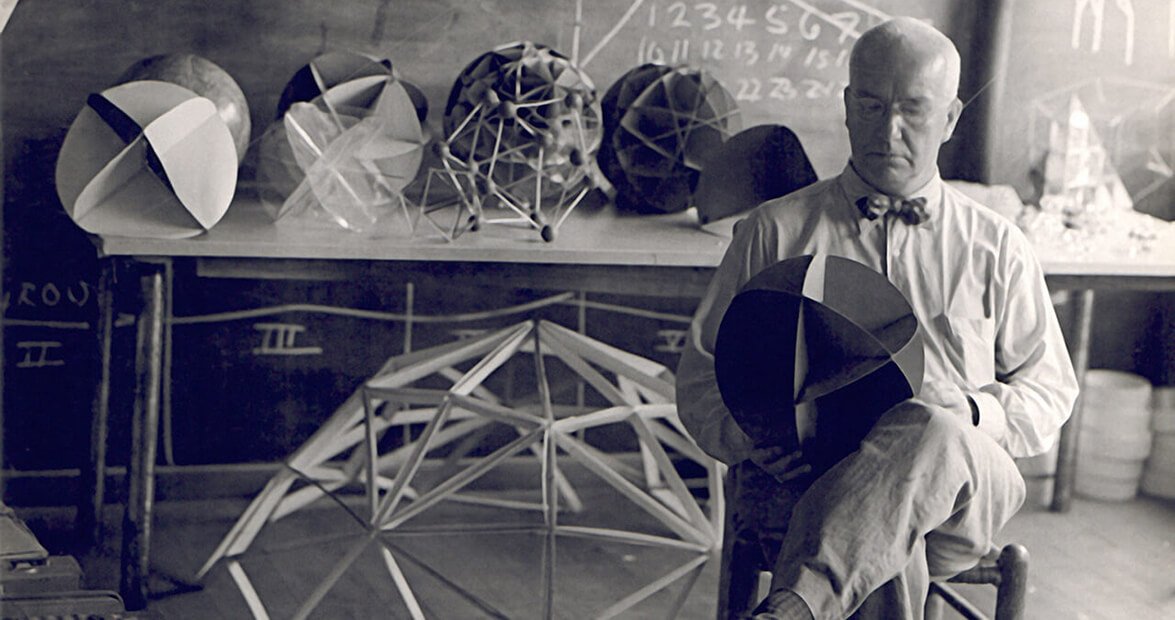

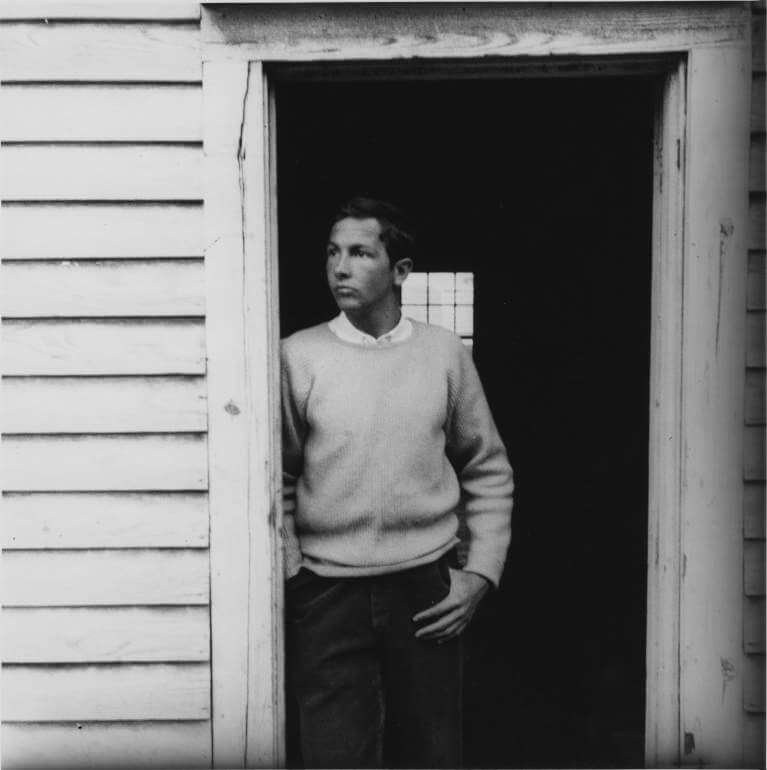

Faculty and alumni included modern dance innovator Merce Cunningham, composer John Cage, architects Walter Gropius and Buckminster Fuller, and a cadre of artists whose bold images would shock America in the 1950s. Rauschenberg, DeKooning, Kline. An advisory board included poet William Carlos Williams and some guy named Einstein.

But Black Mountain was more than the sum of its genius. Deliberately small, defiantly different, the college stood alone in its time, surviving in a rarified air of questioning, doubting, daring.

“A crazy and magical place,” one student remembered, “and the electricity of all the people seemed to make for a wonderfully charged atmosphere, so that one woke up in the mornings excited and a little anxious, as though a thunderstorm were sweeping in.”

Black Mountain had no college president. No board of directors. No stuffy academic departments. There were also no grades, few tests, fewer requirements. So what was there? Chaos? Anarchy?

In lieu of structure, Black Mountain encouraged independent learning backed by a strong sense of community. Each afternoon, following morning classes, students went to work. Some worked on the college farm, others hammered on construction projects, cooked, made art, planned future classes. Each evening, tasked with creating their own education, students filled the small living and dining quarters with endless meetings stirred by whirlwinds of ideas.

“In its idealism,” Artes Magazine wrote, “the college resembled a small religious community; in its reliance on limited means, a pioneering village; in its intense and experimental arts activity, a Bohemian arts colony; in its informal life style and woodland setting, a summer camp.”

At the center of the whirlwind was a shared devotion to art. Black Mountain, another student remembered, realized that “art could be anything. And could be made out of anything, and that it didn't necessarily cross boundaries -- they thought - between theater, the visual arts, dance, music, etc., that you could mix all this up and make a multi-media - or environmental art."

Along with art came the sheer joy of learning together, being together. Isolated in ideology and by the mountains themselves, students were their own entertainment. They gave weekend concerts and plays, sang, hiked, argued, grew.

But utopias have a short shelf life, and Black Mountain was no exception. Despite, or perhaps because of its looseness, clashes among students led to many withdrawals. Faculty likewise came and went, yet while in residence, some showcased the future.

Buckminster Fuller built his first geodesic dome at Black Mountain. John Cage presented his first musical “happening.” Cunningham pioneered modern dance there, and Robert Creeley, before joining the Beats in San Francisco, opened new veins of American poetry. An entire genre of Black Mountain Poets thrived.

But by the 1950s, America had little time for academic experiment. There were jobs to win, a Cold War to wage. Enrollment dwindled. Professors took their art to bigger stages. And in 1957, Black Mountain closed, leaving only its legacy.

You can find that legacy in the experimental colleges that grew out of the 1960s. Hampshire in Massachusetts. Evergreen in Washington. UC Santa Cruz. Goddard College in Vermont. The New College of Florida. . .

You can also find Black Mountain’s legacy just a dozen miles from its old campus. In downtown Asheville, the Black Mountain College Museum keeps the story alive through exhibits and performances dedicated to the spirit of the little college that cracked the ivy wall of academia.

“The template of American art school,” one critic noted, “is still the Black Mountain template.”