SAVED BY THE POISON SQUAD

THE DINNER TABLE — 1900 — The cuisine is not haute, but it sure looks tempting.

Juicy beef — with borax added.

Green peas, laced with copper sulfate.

Pork and beans, with a soupçon of formaldehyde.

Lemon ice cream infused with methyl alcohol

Bon appetit, America!

By 1900, as Americans moved from farms to cities, upstart corporations such as Nabisco, Heinz, and Campbell’s packaged food for the hungry masses.

Label after label touted purity, quality, freshness, but none listed a single ingredient. Then in 1902, a crusading chemist created “The Poison Squad.”

Born on an Indiana farm, Harvey Wiley grew up eating food as fresh as morning. After a stint in the Civil War, Wiley earned a medical degree, then studied chemistry at Harvard. He might have remained a chemistry professor but studies in Germany showed him a new kind of lab.

Throughout Europe, where hundreds of children had died from bad milk, bad meat, food additives were being screened, often banned. Professor Wiley learned how to detect additives, and to be suspicious. Back in Indiana, he turned his suspicion to locally made sugar, honey, and maple syrup. He was shocked.

So-called sugar was mostly corn syrup. Honey likewise, with bits of honeycomb added. Maple syrup? Syrupy yes, but maple?

Wiley’s early studies alarmed the budding food industry, and his character, judged “too young and too jovial,” did not fit academia. In 1882, he left Purdue for Washington, D.C to become chief chemist for the Department of Agriculture.

For the rest of the century, Wiley examined American food. What he found made him sick. Milk was watered down, a pint of water per quart, whitened with chalk or plaster of Paris. Vegetables were greened by copper sulfate. And almost everything contained borax, twenty-mule team.

Wiley lobbied for pure food laws, but “the committee rooms of Congress,” he lamented, “are jammed with the attorneys for the industries, a formidable lobby of influential men who will stop at nothing to kill legislation.” Bills were banned, blocked, tabled. Congress slashed Wiley’s budgets. His name was slurred in industry propaganda. He approached the new century all but defeated, Then came war.

Soldiers in the Spanish-American war ate canned beef by the ton. But cans, packed with borax and formaldehyde, opened with a “poof!” Officers saw troops sickened by “embalmed beef.” One doctor compared its smell to “a dead human body.”

When word reached the public, a pure food campaign began. Inspired, Wiley introduced another bill in 1902. It was defeated, but Congress gave him $5,000 for “Hygienic Table Studies.”

Under cover of jargon, Wiley began recruiting human guinea pigs. Promised $5 a month plus three meals a day, hundreds lined up. Strong stomachs were needed, Wiley warned. Additives would be in each meal, and despite sickness or death, lawsuits were out of the question.

In the summer of 1902, the trials began. Outside a basement kitchen in the Agriculture building, Wiley hung a sign: ”NONE BUT THE BRAVE CAN EAT THE FARE.” And for the next year, a dozen men of “high moral character” chowed down on food laced with every common additive.

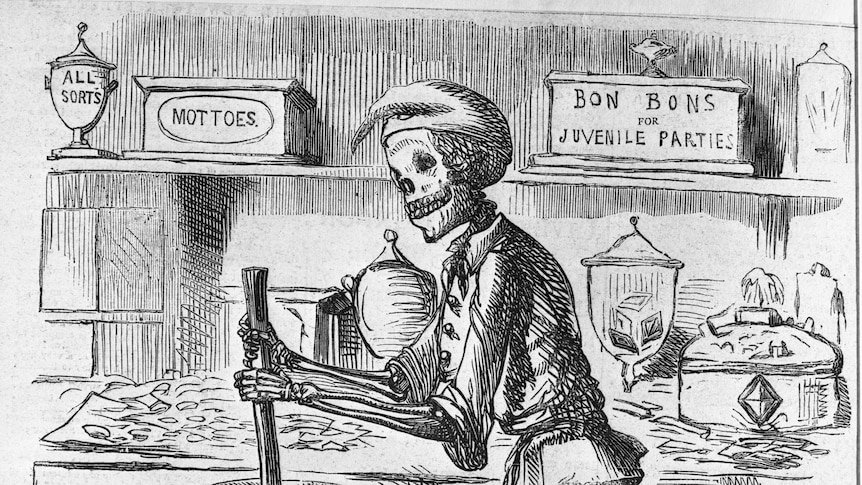

Before and after meals, each strapping man was weighed and measured. Urine, sweat, hair, and stools were analyzed. Sworn to silence, the men ate on, but word leaked. A Washington Post reporter coined the name “the poison squad,” and the squad was soon eulogized in cartoons, poems, songs. . .

Thus all the "deadlies" we double-dare

to put us beneath the sod;

We're death-immunes and we're proud as proud--

Hooray for the Pizen Squad!

Test results were more sobering. Borax caused headaches, stomach aches, vomiting. Copper sulfate damaged livers and kidneys. The public read of strapping young men sickened, nauseated, “losing flesh.”

“One of the reasons that this issue resonated so strongly was that everybody was eating this food,” said Eric Schlosser, author of Fast Food Nation.

Wiley’s “table studies” spread the alarm. By 1904, America’s first celebrity chef, Fanny Farmer, was campaigning for pure food. The National Consumer League joined the fight. Then in 1906, the novel The Jungle revealed nauseating conditions in Chicago meat packing plants.

“I aimed at the public’s heart,” author Upton Sinclair said, “and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

Backed by President Theodore Roosevelt, who had eaten “embalmed beef” with his Rough Riders in Cuba, a Pure Food and Drug Act made its way through Congress. This time, supported by letters from a million women, the bill passed. The so-called “Wiley Act” established the Food and Drug Administration.

Wiley and a team of chemists began banning dangerous additives. Under the Meat Inspection Act, slaughterhouses were cleaned up. Labeling laws required lists of ingredients.

The men of the Poison Squad recovered their health. No one knows what happened to them, but thank you (gag!) for your service. Moving into the new century, the B.S. that Americans had once devoured found other uses. Borax became a laundry agent, copper sulfate a pesticide. Formaldehyde returned to labs.

And Harvey Wiley, after losing a battle against caffeine in Coca-Cola, began writing about food for Good Housekeeping. He died in 1930, on the anniversary of the Wiley Act.

“The Poison Squad,” historian Deborah Blum noted, “was one of the most significant experiments in the 20th century.” But Harvey Wiley offered a more poetic assessment that remains, alas, true.

We sit at a table delightfully spread

And teeming with good things to eat

And daintily finger the cream-tinted bread,

Just needing to make it complete

A film of the butter so yellow and sweet,

Well suited to make every minute

A dream of delight. And yet while we eat

We cannot help asking, “What’s in it?”