THEN ONE LUNAR CHRISTMAS EVE. . .

DECEMBER 24, 1968 — THE MOON — It had been a nightmare year back on Earth. Riots, assassinations, Vietnam. Was America breaking down? Was humanity no better than this? Then one lunar Christmas Eve. . .

During Prime Time, all three networks cut away from sitcoms and cop shows. After brief words from Walter Cronkite and other anchors, horizontal lines filled screens from coast-to-coast. Then: “This is Apollo 8, coming to you live from the moon.”

Everyone knew JFK’s challenge — to land on the moon by the end of the decade. But there were snafus, problems, three astronauts incinerated. Apollo 8 was scheduled to orbit the earth, testing the lunar module, but the module wasn’t ready. The Russians, the C.I.A. reported, were nearing a lunar mission. America needed a boost.

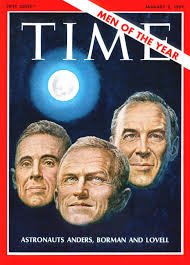

In August, four months before launch, the mission changed. Apollo 8 would orbit the earth once, then make humanity’s first trip into deep space, around the moon and back. “It was a bold move,” astronaut James Lovell recalled. “It had some risky aspects to it, but it was a time when we made bold moves.”

Bold? No astronaut had ridden atop the enormous Saturn V, whose engines had failed a recent test flight. Risky? Astronauts judged their chances of return at 50-50. Two wrote letters to their wives to be opened in the event of. . .

The night before launch, four days before Christmas, Charles Lindbergh met the astronauts and talked of his historic flight. The next morning — “Three, two, one, liftoff, we have liftoff at 7:51 a.m.”

Watching the 360-foot rocket climb, said Susan Borman, wife of astronaut Frank Borman, “was like watching the Empire State Building take off.”

After a smooth orbit above a marbled earth, Apollo 8 fired its engines and headed for the moon. The 68-hour trip was uneventful. Astronauts could not even see the moon they were aiming at. But back on earth. . .

The previous summer, as Chicago police rampaged outside the Democratic National Convention, a chant arose: “The whole world is watching!” Now it was true.

From liftoff, Voice of America beamed reports in English, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, Arabic, and Portuguese. Crowds gathered outside American embassies where TVs showed updates. Villagers walked tropical streets tuning in on radio.

What they heard was mostly static and tech talk — “caaaaa— apogee, perilune, Roger, you are go for TLI. . .” Scheduled for a Christmas Eve closing broadcast, could these buttoned-down men with the “right stuff” capture the wonder of it all?

Before the flight, a NASA spokesman warned Borman. “You’re going to have the largest audience that’s ever listened to or seen a television picture of a human being, on Christmas Eve. And you’ve got, I don’t know, five or six minutes.”

“What should we do?” Borman asked.

“Do whatever’s appropriate.”

Frank Borman was a pilot, not a poet. How could Apollo 8 do justice to the moon, the journey, the cosmos? A Christmas story? A Santa Claus scenario? A riff on Jingle Bells? All seemed trivial or silly. Borman turned to friends, but all were stumped. Then a friend’s wife had an idea.

Christine Laitin had been a ballerina, a painter, a member of the French Resistance. “Why don’t you begin at the beginning?” she said.

Astronauts had their message, soon printed on fireproof paper. But in the shadow of the moon, they were too amazed to think about the upcoming broadcast. “We were just sixty miles above the craters,” Lovell recalled, “and we were sort of like three school kids looking in the candy store window.”

The danger doubled when the craft flew behind the moon. “See you on the other side,” Lovell said. Then silence. Thirty minutes later, when Apollo 8 came around the dark side, human perception of the earth took one giant leap.

“Oh my God,” Borman said. “Look at that picture over there! Here’s the earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!” Fumbling for color film, Bill Anders thought he’d missed the moment but the wonder appeared in the other window. An earthrise.

After nine orbits, one remained. On Christmas Eve, as lunar seas and craters spilled across small screens around the globe, the three test pilots struggled for words.

“The moon is a different thing to each one of us,” Borman began. He described “a vast, lone, forbidding type existence.” Lovell agreed. “Makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth.” Anders marveled at lunar sunrises and sunsets.

With minutes remaining, Borman pulled out the message. “We are now approaching lunar sunrise, and for all the people back on earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message that we would like to send to you.”

We listened (my family at the dinner table) and watched the unimaginable — the moon and its craters skimming below. Anders began.

In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep.

For the next few minutes, all the anxiety, all the rancor, all the Cold War politics disappeared as if behind some dark side. Anders read through God divided the light from the darkness. Lovell continued: And God called the light Day. . .

More craters scrolled below as Borman went on.

And God said, “Let the water under the heaven be gathered together. . .”

Finished with the beginning of the beginning, Borman signed off. “And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night and good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you — all of you on the good Earth.” Screens went dark.

After a flawless return and splashdown, Apollo 8 astronauts were celebrated, paraded, honored. They received 100,000 letters. One read, “Thank you for saving 1968.” But they had done more.

The Book of Genesis, Apollo 11’s Michael Collins said, “was a very nice touch. It fit very nicely into getting away from all this machinery and let’s get down into the fundamentals of what makes all this happen, why are we here.”