CAPOTE -- "A CHRISTMAS MEMORY" AND A SEASON'S TRUTHS

The story begins simply: Imagine a morning in late November. A coming of winter morning more than twenty years ago. . .

What follows is as much miracle as memory. Because although it lacks the usual Yuletide baubles, Truman Capote’s “A Christmas Memory” is saturated with the feelings and flavors of this season.

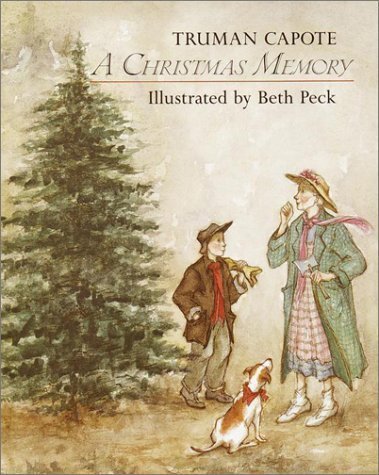

First published in 1956, the story of a boy and his aging, childlike cousin sharing a bare bones Christmas has become a classic. It has been told and re-told on TV, on Broadway, in an opera, and numerous readings. Reading “A Christmas Memory” is now part of many personal Christmas memories. I used to read it annually to my children, and still do, to myself. Spoiler alert: There is no way to finish the story with dry eyes.

But was this a memory? Or was it, as said of Capote’s In Cold Blood, part fiction, part fact? The facts are mixed., yet “A Christmas Memory” does contain a miracle — a tragic childhood turned, for one season, into a magic childhood.

Just today the fireplace commenced its seasonal roar. A woman with shorn white hair is standing at the kitchen window. She is wearing tennis shoes and a shapeless gray sweater over a summery calico dress. . . “Oh my,” she exclaims, her breath smoking the window pane. “It’s fruitcake weather!”

Truman Streckfus Persons was born in 1924. Though a child of the Deep South, his boyhood was straight out of Dickens. His father, a smooth talking con man, drifted in and out of his life, making and breaking promises. His mother, busy dancing and having affairs, had little time for her son. Truman was left in hotel rooms or with his mother’s family in Monroeville, Alabama. And that’s where the story begins.

We are cousins, very distant ones, and we have lived together — well, as long as I can remember. Other people inhabit the house. . .

“Other people” were the Faulks — three sisters and two brothers, the latter pair slipping from Capote’s “memory.” But two sisters emerge to play Scrooge, and one becomes the story’s soul. Although Capote never names her, Nanny Faulk, known as Sook, was nearing sixty when Truman moved into the family home. And just as Capote wrote. . .

In addition to never having seen a movie, she has never: eaten in a restaurant, traveled more than five miles from home, received or sent a telegram, read anything except funny papers and the Bible, worn cosmetics, cursed, wished someone harm, told a lie on purpose, let a hungry dog go hungry.

Some thought Sook, in the rude parlance of the time, “retarded.” Capote writes that she is “still a child.” Yet he later wrote a friend: “I had an elderly cousin, the woman in my story ‘A Christmas Memory,’ who was a genius.”

Genius or child, Sook gave Truman, whom she called Buddy, all the love he had missed. And here is where memory comes alive. Each December, Buddy and Sook made their own Christmas traditions. These included going into the woods to chop a tree, flying kites, and making fruitcakes. Some cakes went to friends, others to “people who’ve struck our fancy” — Baptist missionaries, a traveling knife grinder, and President Roosevelt. Thank you cards and letters were kept in a scrapbook.

Now a nude December fig branch grates against the window. The kitchen is empty, the cakes are gone. . .

But memory is selective. Capote does not mention that Sook was addicted to morphine, given her after a mastectomy. He also says nothing about his parents who drifted in to make promises, then left again. Some truths are too sad for this season.

“Buddy, are you awake?” It is my friend, calling from her room. . . “I feel so bad, Buddy. I wanted so bad to give you a bike. I tried to sell my cameo Papa gave me. Buddy — “ she hesitates as though embarrassed. “I made you another kite.” Then I confess I made her one, too. . .

Finally, memory turns to magic when, on Christmas morning after opening the others’ dull presents. . .

“Buddy, the wind is blowing.” The wind is blowing, and nothing will do till we’ve run to a pasture below the house. . .

Capote says this was their last Christmas together. It was. But he was not sent to “a miserable succession” of military schools. He was taken back by his mother, by then re-married to businessman Joe Capote and living in Brooklyn. Capote also neglects to mention that even as a boy, he was a writer. Winning attention, winning prizes, he survived still more neglect and was soon weaving his childhood into fiction.

In his mid-twenties, Capote’s stories and persona made him a celebrity. Breakfast at Tiffany’s led Norman Mailer to call him “the most perfect writer of my generation.” By 1966, one biographer wrote, Capote “had the golden touch.” In Cold Blood was a huge bestseller, jumpstarting a new genre — creative non-fiction. And on a coming of winter evening, just weeks before Geraldine Page gave a heart-wrenching performance in TV’s “A Christmas Memory,” Capote held his Black and White Ball, with its fabulous guest list and infamous extravagance.

He never finished another novel. A gifted writer can turn tragedy to magic, only to have his childhood chase him into alcohol and drugs. But a generation after Capote’s death, it is his Christmas memory, and not the sadder facts, that we recall.

That is why, walking across a school campus on this particular December morning, I keep searching the sky. As if I expected to see, rather like hearts, a lost pair of kites hurrying toward heaven.