EDISON'S LITTLE GLOBE OF SUNSHINE

MENLO PARK, NJ, NEW YEAR’S EVE, 1879 — In December’s darkness, the glow could be seen from the train station. Drawn to it like moths to a flame, hundreds from up and down the East Coast headed for the home of the Wizard.

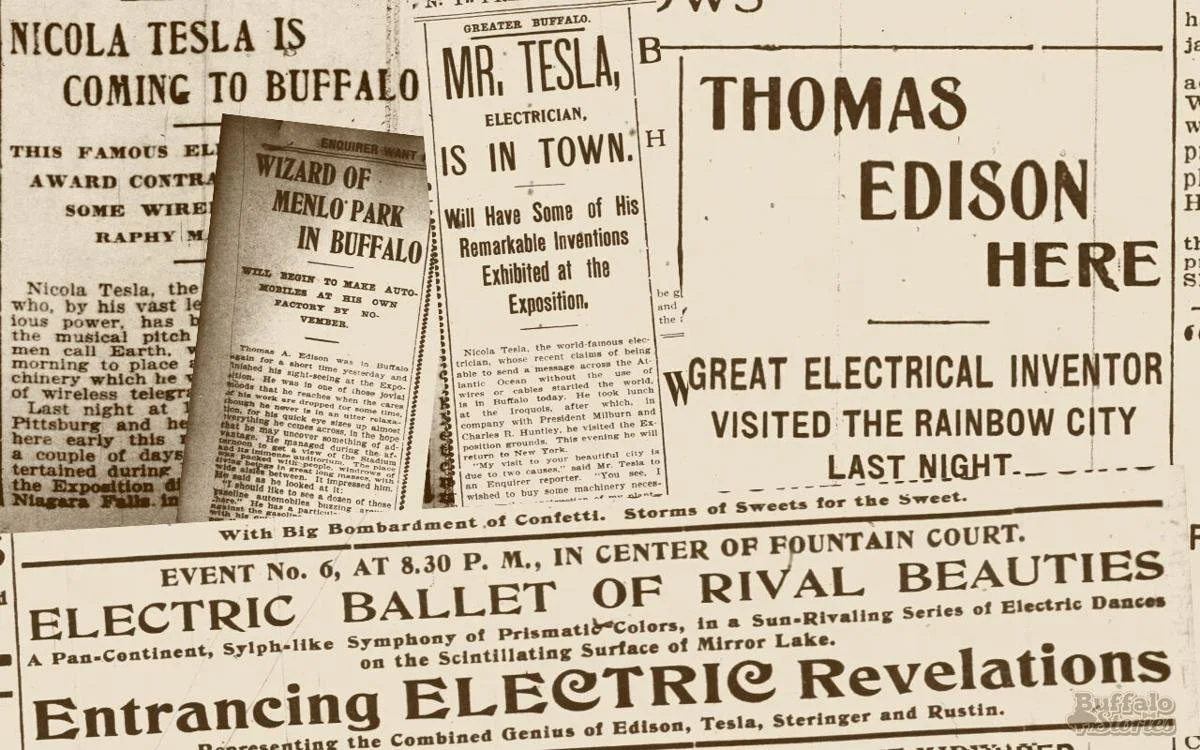

At 32, Thomas Edison was already famous. His 250 patents were mostly for telegraphs and hulking batteries, scarcely household items in the Gilded Age. But his phonograph — a machine that talked — had astonished the world. What wonder would “the Napoleon of invention” provide next?

Throughout the decade-long struggle for an electric light, Edison sat on the sidelines. His few experiments made short-lived lights, just single bulbs. Every other inventor was thinking small, seeking systems to light individual homes. But Edison knew that no money would be made in electric lighting unless it could illuminate a city, and that seemed impossible. Until. . .

In the fall of 1878, Edison toured a small factory in Connecticut. There he saw several bulbs lit by a single source. Edison, wrote one of the reporters who charted his every move, “ran from the instruments to the lights, and from the lights back to the instruments. He sprawled over a table and with the simplicity of a child, and made all kinds of calculations.”

Before departing, Edison told the factory owner, “I believe I can beat you making the electric light. I do not believe you are working in the right direction.” Then he headed home to Menlo Park where his greatest invention — the first research and development lab — awaited.

“It was all before me,” he recalled. “I saw the thing had not gone so far but that I had a chance.”

Within a week, teamed with the engineers he called his “muckers,” Edison had a working bulb with a platinum filament burning brightly. Reporters swooned.

EDISON’S NEWEST MARVEL

SENDING CHEAP LIGHT, HEAT,

AND POWER BY ELECTRICITY

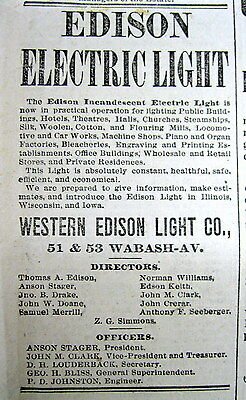

Edison said he would soon “light the entire lower part of New York City, using a 500 horsepower engine.” The Edison Electric Light Company sold its first stock, most to Edison himself.

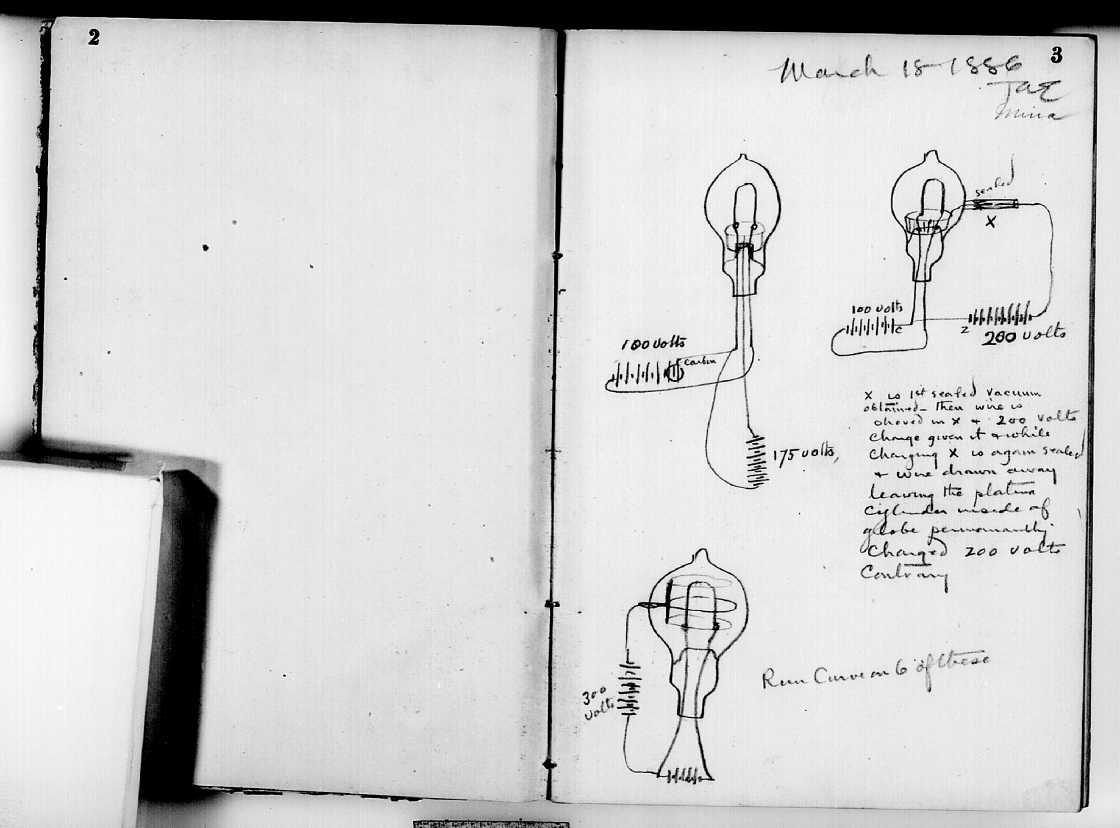

But the Wizard did not tell investors that his platinum light lasted only an hour. A better filament was needed. On into 1879, the search continued, centering on carbonized, i.e. charred, materials.

Cotton and linen thread. Wood splints. “Papers coiled in various ways, also lamp black, plumbago, and carbon in various forms, mixed with tar and rolled out into wires of various lengths and diameters. . ." Edison even charred hair from the beards of two machinists, his engineers betting which would burn out first. Neither hair lasted long.

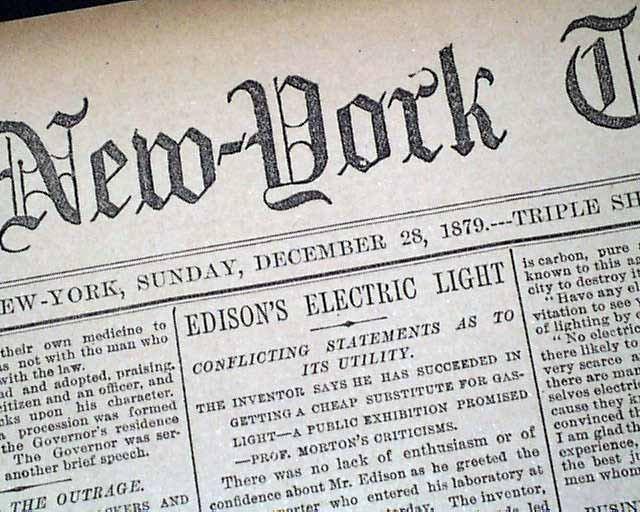

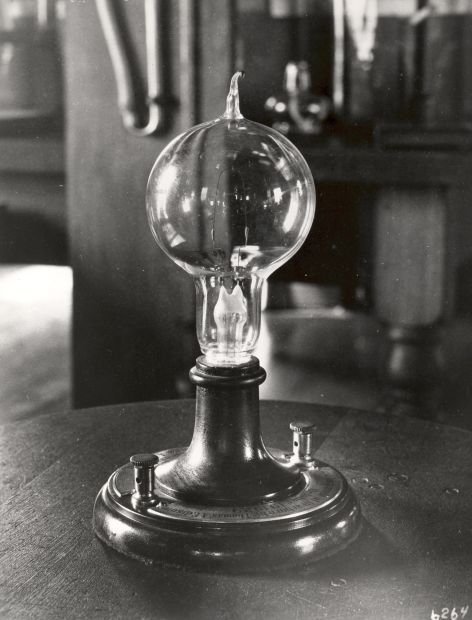

Then in October 1879, Edison broke through. A single strand of carbonized cotton thread burned through the night and into the next afternoon. Within days, Edison filed a patent for “Improvement on Electric Lamps.” Now to show the public.

But why electric light? Gas lamps already burned in every American home, and on the streets of major American cities. Darkness had been conquered. Still, gas had to be lit lamp by lamp. Gas flickered, smoked, blew out with a breeze. And gas ignited whatever it touched. The most recent of many “great fires” had destroyed Chicago.

Electric light, Edison knew, was more than illumination. Along with the fortune to be made, electric light, like a bulb above a thinker’s head, embodied genius. Electric light was the future.

By early December, Edison’s compound in Menlo Park was fully lit by electricity. Stray visitors began coming to bear witness to the miracle. Then just before Christmas, the New York Sun announced Edison’s plans for New Year’s Eve.

“Edison’s electric light, incredible as it may appear, is produced from a tiny strip of paper that a breath would blow away. Through this little strip of paper passes an electric current, and the result is a bright, beautiful light, like the mellow sunset of an Italian autumn.”

On December 31, crowds began arriving at dusk. Following the glow, some 3,000 visitors, many in top hats and gowns, stepped into the future. Twenty brilliant bulbs lined the walkway. Inside the lab, another two dozen glowed on tabletops. And there in the center of the glow was the Wizard himself, talking to investors, flipping lights on and off, basking in the acclaim.

Reporters competed to describe this first public display of electric light. Each bulb was “the flash of a thousand diamond facets,” “a veritable Aladdin’s lamp,” “a little globe of sunshine.”

Walking back into the night, people marveled at the magic. And when the New Year came, 1880 saw Edison and his muckers test thousands more filaments, finally settling on carbonized bamboo that burned for hundreds of hours.

That April, the streets of Menlo Park were dug up to lay wires. By November, the little town was the first in the world with electric streetlights. The wizard had entered late, but outwitting mere engineers, he won the race.

Why, many asked, hadn’t anyone else dreamed up the innovations that made mass lighting possible? Because, one scientist noted, “no one else is Edison.”