THE NIGHT THE STARS FELL

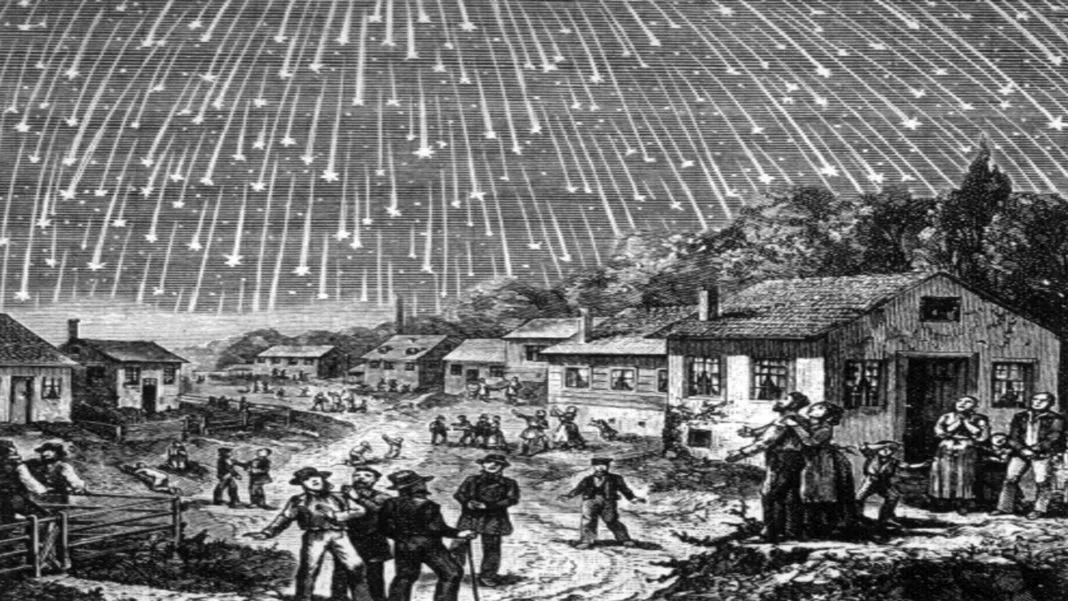

MANHATTAN, NOV. 13, 1833 — Eager to hit the road, a merchant rises at 5 a.m. on this balmy autumn night. Seeing light through his window sash, he thinks dawn has come. He opens the sash. The sky is on fire.

“I called to my wife to behold and while robing, she exclaimed, ‘See how the stars fall!’”

Meteor showers can be disappointing. Those who stay up late to see the Perseids in August or the Leonids in November usually see just a few bright streaks in one corner of the sky. But on “The Night the Stars Fell,” “shower” hardly described the fireworks of the firmament.

From 1:00 a.m. until dawn, some 75,000 “shooting stars” per hour blazed in skies across America. Streaks of yellow, huge orange fireballs, falling candles, scorching trails astonished and terrified the nation.

— “Like large flakes of falling snow.”

— Sparks “such as one sees when molten iron is running into or from the ladle.”

— “The most sublime and awful scene ever presented to mortal view.”

Sublime or awful? Reactions depended on one’s view of the heavens, or of heaven itself. And in 1833, those views were starkly divided.

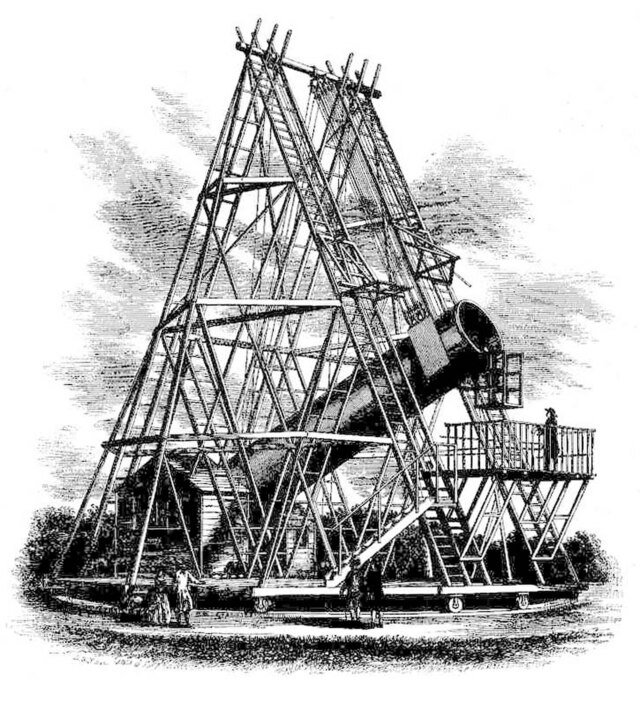

Astronomy had come far since Galileo. Telescopes had discovered one new planet, bringing the known number to seven. Comets were understood to orbit the sun, returning with clockwork predictability. Yet everyone knew space was filled with a substance called “ether,” and for all but a few, the heavens were God’s realm.

Since the 1790s, the Second Great Awakening had spread tent revivals from Maine to Mississippi. Evangelicals, Methodists, and Baptists alike believed their days on earth to be numbered. Preachers pounded pulpits, warning of a God wielding “fire and brimstone.” And then one November night, fire and brimstone fell. . .

In Manhattan, the early-rising merchant and his wife “felt in our hearts that it was the sign of the Last Days.” In Georgia, one newspaper reported, “people were frightened to their knees, dust-covered Bibles were opened and dice and cards were thrown into flames.”

In North Carolina, the faithful “filled the air with their shrieks while many muttered over their prayers with a fervor and devotion which denoted apprehension of some fearful calamity.” In Alabama, one freed slave later recalled, “the white folks started callin’ all the slaves together, and for no reason, they started tellin’ some of the slaves who their mothers and fathers was, and who they’d been sold to and where. You see, they thought it was Judgment Day.”

“Well, this one thing I do know,” said a farmer. “Escape or not, live long or die soon I will never touch another drop of liquor.”

Hour after hour, as the “train of fire” flared, those who knew their Bible recalled Revelations 6:13: “The stars in the sky fell to the earth like unripe figs shaken loose from the tree in a strong wind.”

But others scoffed at apocalypse. “Shooting stars, falling stars, meteors, eclipses, and other phenomena of the heavenly bodies occurred in ancient times as they do now,” the New York Star wrote. Rather than fear omens, we should be “guided by the lights of science. . . What lately occurred in the heavens has before occurred and yet the world was not destroyed.”

At Yale, one “natural philosopher” agreed. Denison Olmstead saw “The Night the Stars Fell” as a chance to conduct “citizen science.” Olmsted quickly sent out a call for observations.

Yet that “awful” night had sown its terror. “We pronounce the Raining Fire which we saw on Wednesday morning last an awful TYPE,” one newspaper proclaimed, “a sure Forerunner, a merciful sign of that great and dreadful day which the inhabitants of the Earth will witness when the Sixth Seal shall be opened.“

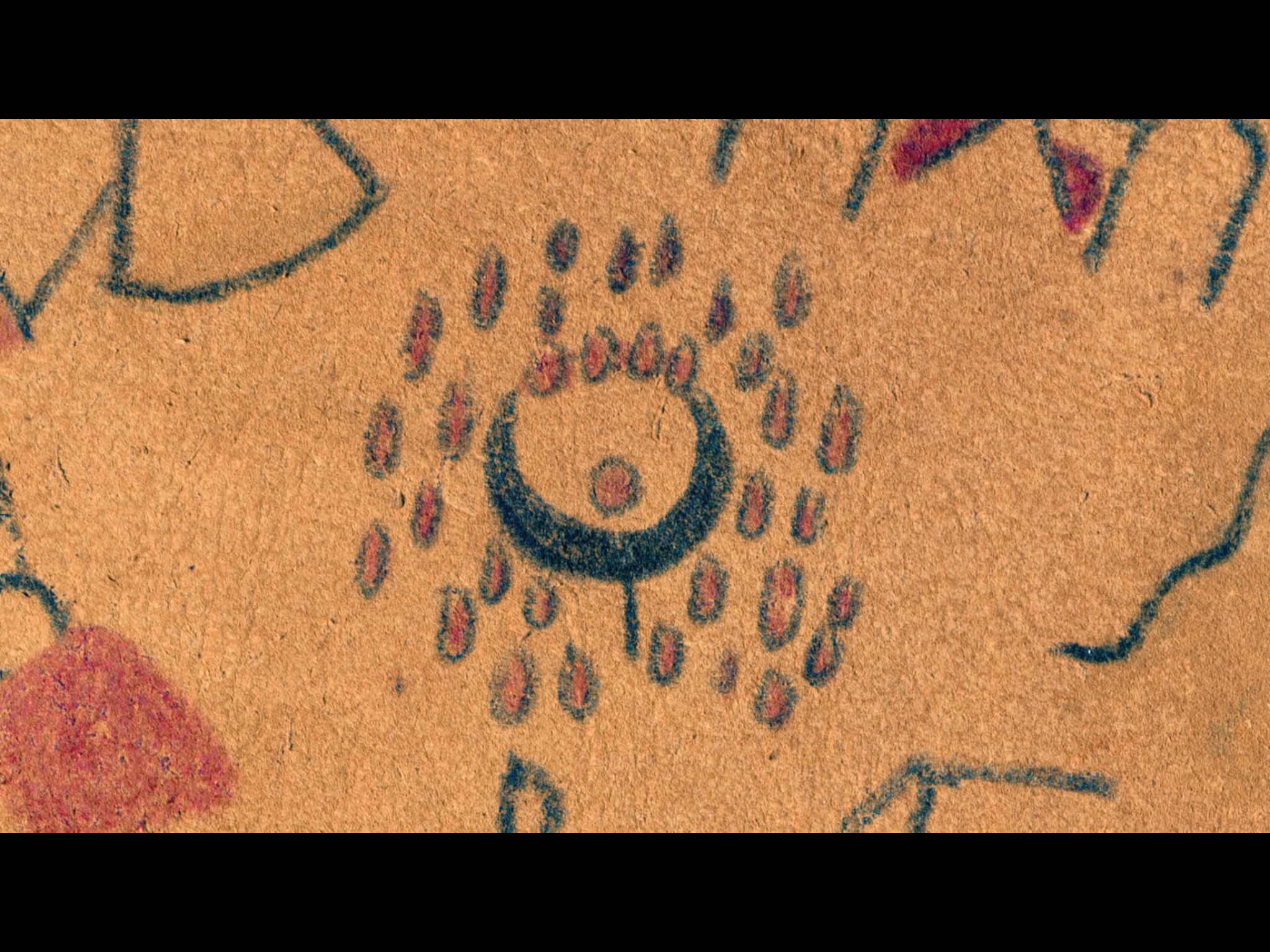

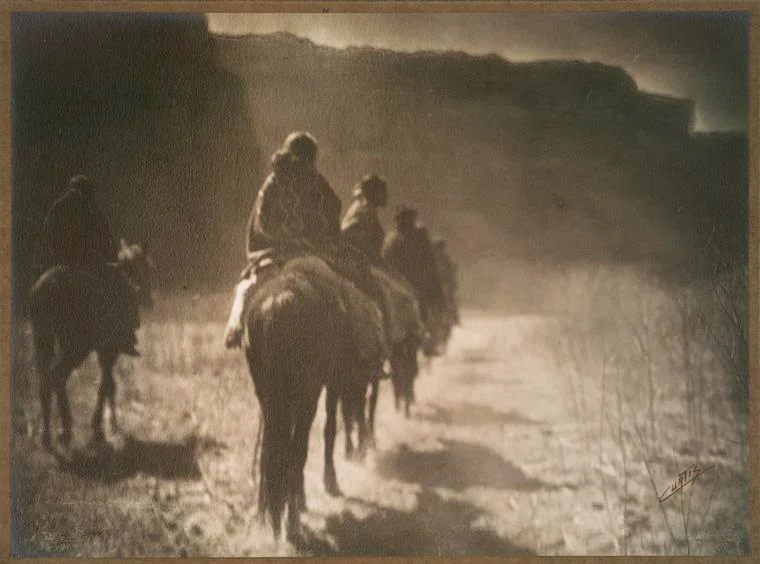

Native-Americans were also frightened. “The Kiowas were camped in the Wichita Mountains,” novelist M. Scott Momaday recounted. “They were awakened by the light of flashing stars. They ran out into the false day and were terrified. They thought of the year and the event as an omen. Bad things came after that.”

Plenty of “bad things” came after that. War, disease, upheaval. But the following April, Yale’s Professor Olmstead shone “the lights of science” into the ominous darkness. No stars had fallen. God had not rained fire and brimstone. A comet was to blame.

“The meteors consisted of the extreme parts of a nebulous body or comet which revolves around the sun in an orbit interior to that of the earth,” Olmstead wrote. When the professor’s “Observations on the Meteors of November 13, 1833” was excerpted in newspapers, those who could read or reason learned a thing or two about the heavens. The rest remained in fear.

“We are all afraid,” Jacob Bronowski wrote in The Ascent of Man, “for our confidence, for our future, for the world. That is the nature of the human imagination.” Even today, when astronomers have charted and photographed the cosmos in all its astonishing beauty, some seek omens to predict the coming year, or chart the looming apocalypse.

Faced with events beyond explanation, some fall to their knees, shriek or mutter. But “The Night the Stars Fell” offers a call to courage. “What lately occurred” in our own world “has before occurred and yet the world was not destroyed.” So. . .

Shall the rest of this new year, this long night, be “sublime or awful?” Draw your own conclusions.