BOB AND RAY AND WALLY AND KOMODO DRAGONS

TIMES SQUARE, 1955 — “Wally Ballou is up to some sort of hijinx today. He’s just signaled that he’s ready to go on the air, so come in, please, Wally Ballou.”

“— ly Ballou here, winner of the Gormley Diction Award, standing in New York’s Times Square with a gentleman who. . .”

— ran a hand made paper clip factory that paid workers 14 cents a day;

— lobbied to make pizza America’s traditional Christmas dinner;

— grew cranberries to make cranberry shortcake, and was surprised to learn of other uses;

— ran a four-leaf clover farm. . .

From the heyday of radio to the spread of the Internet, Bob and Ray made the banal seem commonplace and the inane seem endless.

“They feature Americans who are almost always fourth-rate or below,” wrote Kurt Vonnegut, who once submitted sketch ideas to Bob and Ray. “While other comedians show us persons tormented by bad luck and enemies and so on, Bob and Ray’s characters threaten to wreck themselves and their surroundings with their own stupidity. . . Man is not evil, they seem to say. He is simply too hilariously stupid to survive.”

Blithe ignorance being eternal, Bob and Ray continue to amuse us. The DNA of their humor spirals through American comedy from early George Carlin to SNL, from Letterman to “The Daily Show.” Americans may not be as “hilariously stupid” as Bob and Ray suggested — or we just might be.

Because they so often linked their names — the Bob and Ray Weekend Camp, the Bob and Ray Lucky Phone Call — a Bob and Ray biography seems in order.

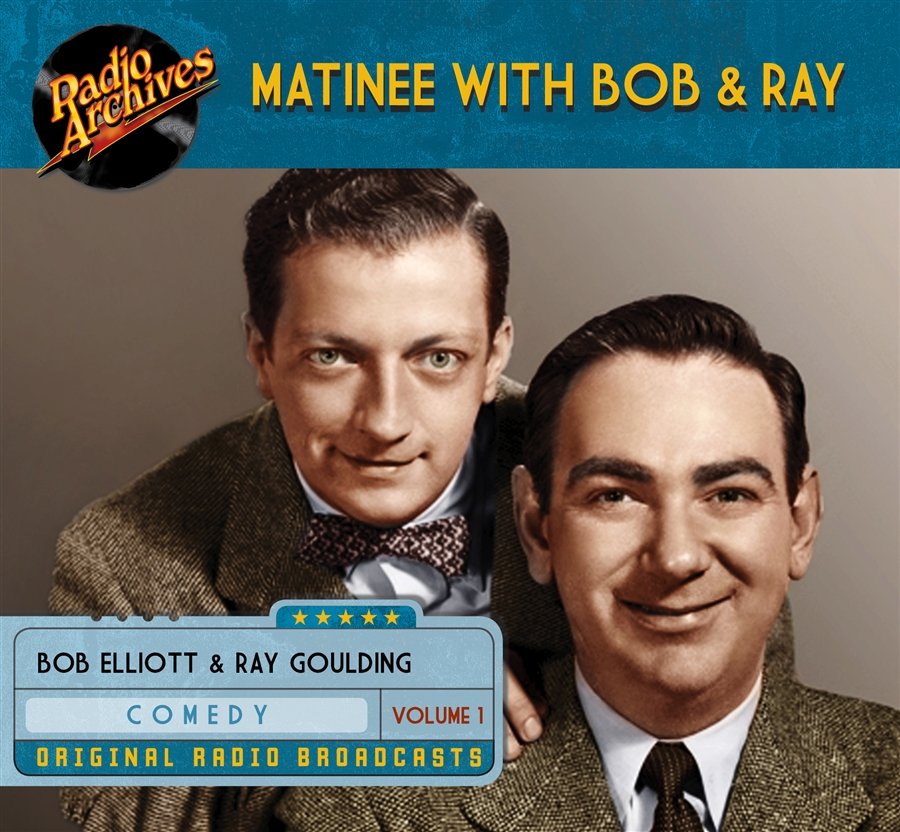

Bob and Ray were born near Boston in 1922/1923. Bob and Ray grew up listening to radio, reading the gentle wit of Robert Benchley, and surviving the Depression with dreams of being announcers. Bob and Ray served quietly in World War II then came back to Boston where they met at station WHDH. Bob (Elliot) was a deejay while Ray (Goulding) was his newsman.

During dead-air, the two began talking, joking, ad-libbing. In 1947, when some ad-libs aired, they got their own show. “Matinee with Bob and Ray” featured gags they would run for 40 years. Wally Ballou interviews, parodies of soap operas (“One Fella's Family"), and sendups of radio shows (“The 64-Cent Question,” "Matt Neffer, Boy Spot-Welding King of the World") had Boston tuning in daily.

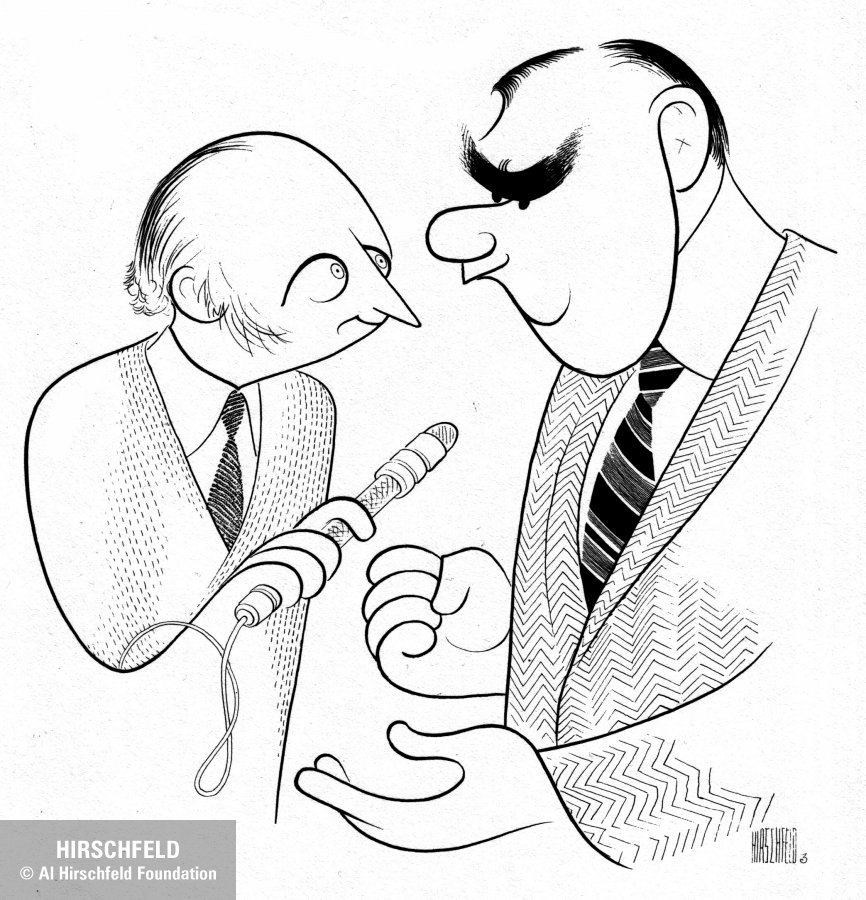

New York soon noticed, as did the so-called Boob Tube. In 1951, Bob and Ray debuted on NBC-TV. They had hair then, but otherwise their droll humor was already firmly fixed. And their timing, on screen and off, was perfect.

TV was taking itself very seriously. Borscht Belt stand-up was still out in the Catskills. Other TV comedians, from Red Skelton to Milton Berle, were clowns. Thoughtful people, those concerned about TV, radio, and their effects on America, had only one on-air outlet — Bob and Ray.

“They work masterfully close to the very things they are gently mocking,” the New York Times wrote, “and this gives their sensible nonsense its special flavor. For one thing it shows just how much arrant nonsense we actually accept in television.”

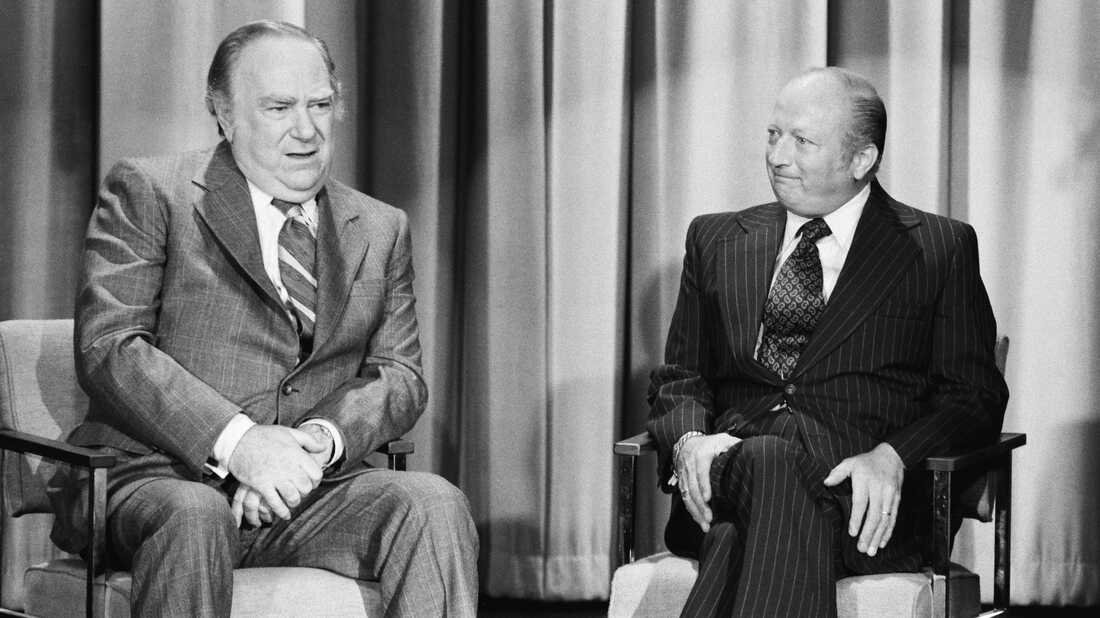

On into the 1970s, Bob and Ray were media fixtures, on their own radio shows, commercial voice-overs, as guests on Carson, SNL, and elsewhere. Their cast of characters, from sportscaster Biff Burns to caricatures Arthur Sturdley, Dr Joyce Dunstable, and Elmer W. Litzinger, spy, kept coming.

“It just keeps happening to us,” Ray said. “I suppose each new generation notices that we are there."

And each new generation laughed along with lampoons that never got old. To wit:

— The Croftweiler Industrial Cartel ("Makers of all sorts of stuff, made out of everything.")

— Cool Canadian Air ("Packed fresh every day in the Hudson Bay and shipped to your door.")

— Kretchford Braid and Tassel ("Next time you think of braid or tassel, rush into your neighborhood store and shout, 'Kretchford'!")

Aging comedians often follow one of two scripts — a softened repetition (Bob Hope, Garrison Keillor) or bitter cynicism (Carlin, Mark Twain.) But Bob and Ray rebooted themselves again and again.

Their final decades saw them re-run classic routines but also craft new ones for new audiences. Gone were the fast-talking ad-libbers. In their place, just as funny, were the old men in chairs deadpanning the latest dumbness.

The droning expert — on whooping cranes or komodo dragons. The clueless collector — of “numbers you get where they give out numbers.” The “Slow Talkers of America,” and. . .

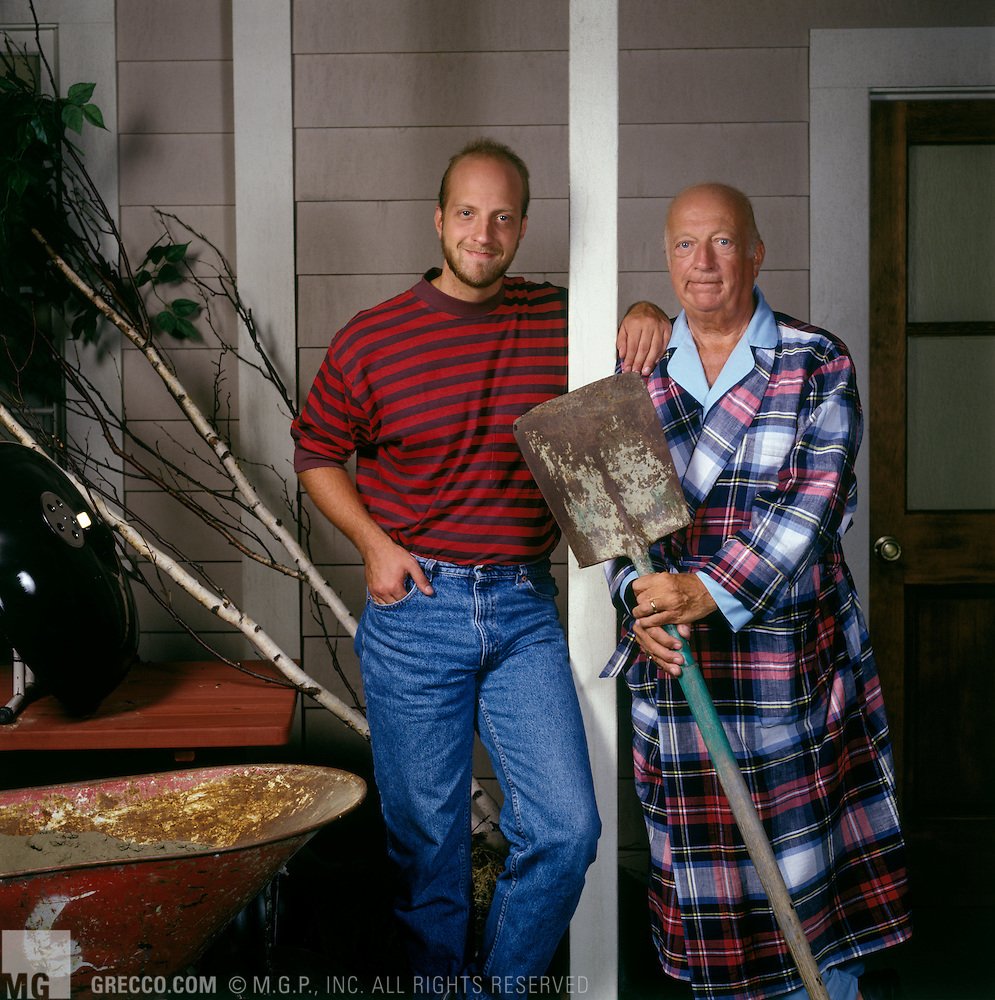

In the 1980s, Bob and Ray did regular bits for NPR and a second stage show, not Broadway as in 1970, but at Carnegie Hall. They might have gone on forever, but kidney disease curtailed Ray’s schedule. When he died in 1990, Bob teamed with his son Chris Elliot in the sitcom “Get a Life,” then made various appearances on TV and radio.

Bob Elliott died in 2016, yet on Youtube, the Internet Archive, and elsewhere online, Bob and Ray seem immortal.

And somewhere out there, in some remote corner of America, —ly Ballou is interviewing another bumbling collector, promoter, or entrepreneur. And when he is finished, you’ll hear the Bob and Ray Signoff.

“This is Ray Goulding, reminding you to write if you get work.”

“And Bob Elliott, reminding you to hang by your thumbs.”