ROGER MILLER -- COUNTRY'S WACKY WORDSMITH

NASHVILLE 1950s — Country music was in a dark hollow — “where the sun don’t never shine.” The Opry was still Grand but getting Old. Every lanky guy with a git-tar wanted to be Hank and every gal with a perm and pressed blouse wanted to be Patsy. But sittin’ ‘round drinkin’ with the rest of the guys were the outlaws. Willie and Waylon, and a witty Oklahoman named Roger.

Roger Miller did not write songs, he exuded them. “Everything he said was a potential song,” a colleague remembered. “He spoke in songs.”

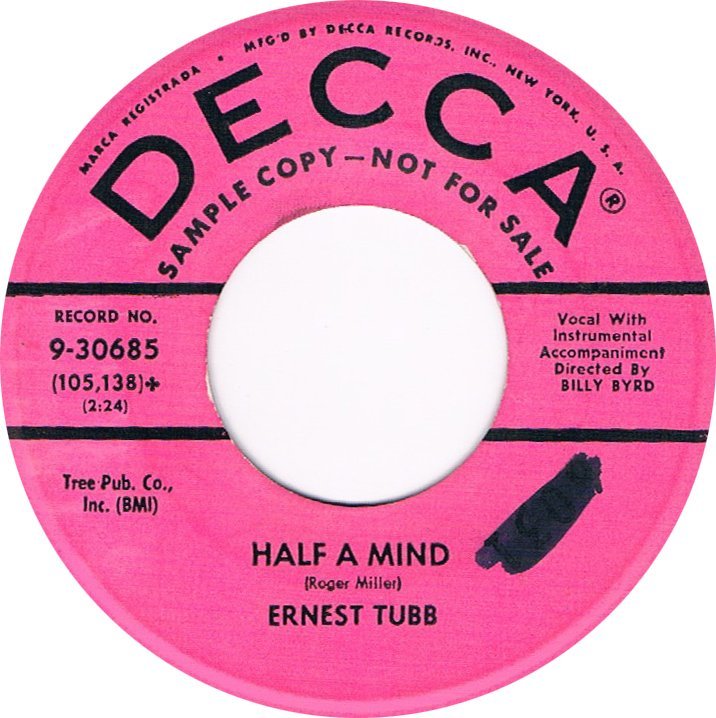

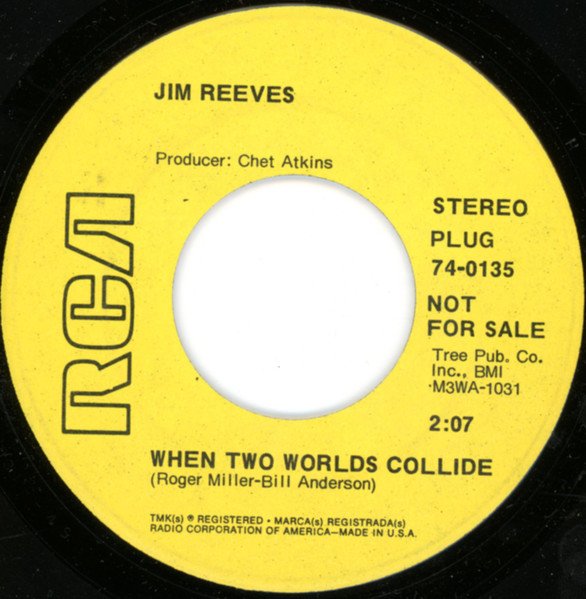

The songs were ballads for crooners like Ernest Tubb and Jim Reeves. “A songwriter will write a lot of things and get a few recorded,” Miller said, “But there’s some overflow. The overflow is what they would never let me record. They said, ‘It’s too far out.’” Then after a decade adrift, Miller’s overflow lifted Nashville out of its dark hollow.

Roger Miller was “a genius,” “a wild child,” “the most spontaneously creative human being I’ve ever met.” His songs remain country classics. But behind the wordsmith was a sad man struggling with addiction, hoping for one more high, one more hit.

“Good ain’t forever and bad ain’t for good”

“The things I tried to do like somebody else always came out different," Miller said. "It was frustrating—until I learned I'm the only one that knows what I'm thinking."

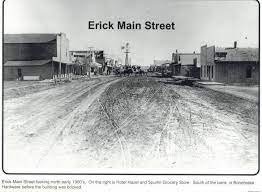

Miller’s sadness grew from a lonely childhood. Just a year old when his father died, he was sent to live with an uncle in Erick, Oklahoma, a Dust Bowl town “so poor you’d have to spell poor with five O’s.”

Plowing and picking cotton, Miller left school in eighth grade. Bought a $12 guitar and dreamt of being the next Hank. Played gigs until the night he got drunk and stole a guitar. Given the choice of jail or the army, “my education was Korea, clash of ‘52.” Stationed back in Atlanta, he played fiddle in bands and soon headed for Nashville.

Miller spent the 1950s “caught between big-band music and rock-and-roll." A few of his songs were minor hits — for others — but five record companies signed him and cut him.

“Roger was the most talented, and least disciplined person that you could imagine,” one singer said. Strewing half-finished songs and one-liners, Miller ended up in Hollywood where the tiny label Smash Records took a chance, paying him $100 a song. In January 1964, he recorded sixteen songs in two days. The first was his breakthrough.

“There’s so many bends before the break finally happens.”

From its opening riff to its wondrous wordplay, “Dang Me” was like nothing Nashville, or America, had heard. Others sang of trucks and trains, but Roger Miller made words “my toys.”

Just sittin’ round drinkin’ with the rest of the guys

Six round they bought and I bought five

Spent the groceries and half the rent

I lack fourteen dollars of havin’ twenty-seven cents, so Dang Me…

He could even rhyme the unrhymable:

They say roses are red and violets are purple

Sugar’s sweet, and so is maple surple

“Dang Me” was followed by an homage to teenage drinking, “Chug-a-Lug.”

Juke box and sawdust floor

Somethin’ like I ain’t never seen,

Hell I’m just goin’ on fifteen

But with the help of my finaglin’ uncle. . .

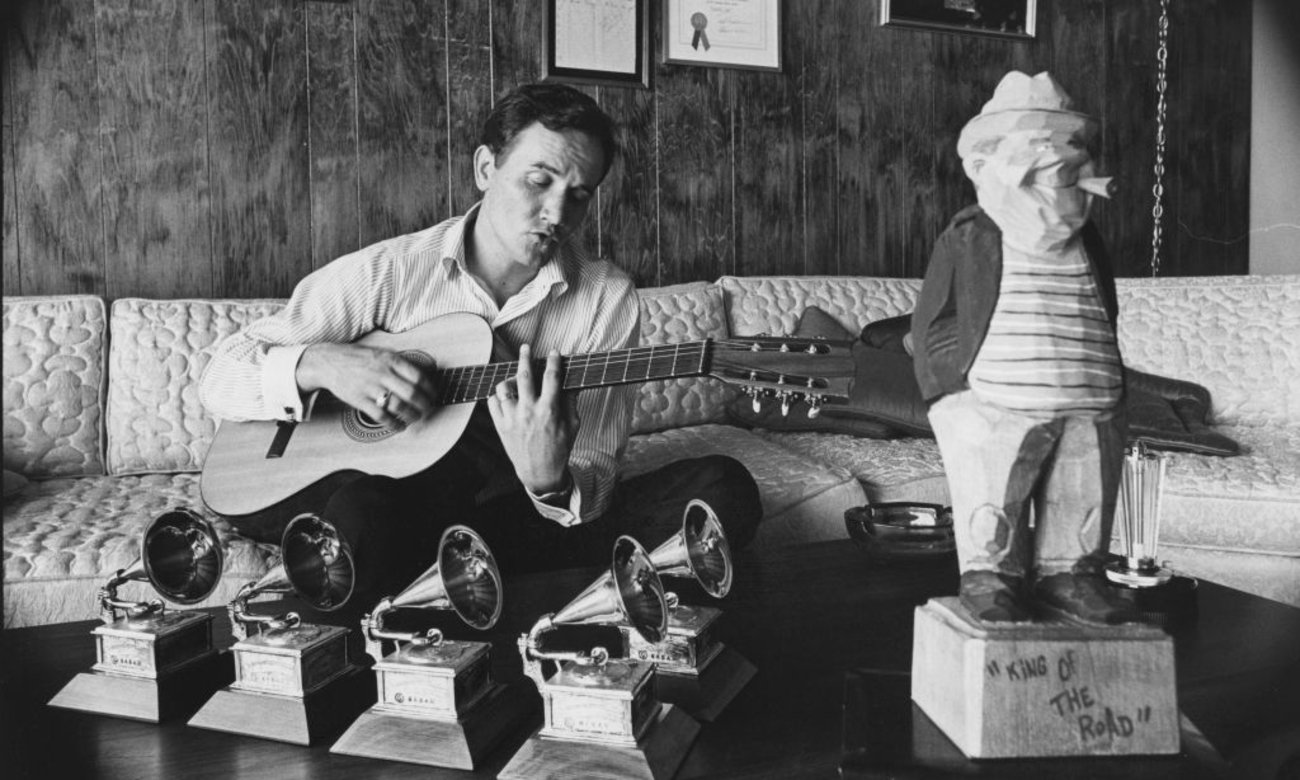

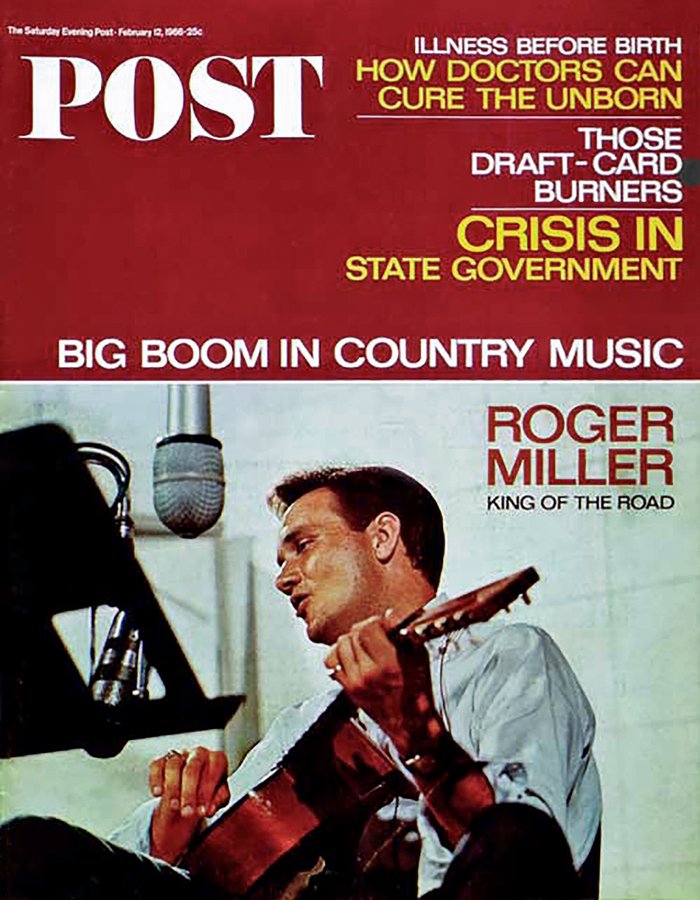

Suddenly, the poooor boy from Oklahoma was the hottest star in Nashville. In two years, he won eleven Grammys, had his own TV show, flew in a Lear Jet. Then one morning outside Chicago, he spotted yellow letters on a red barn reading “Trailers for sale or rent.” By summer, “King of the Road” topped both country and pop charts.

‘’Roger was responsible for making country music cool to the pop music world,” Kris Kristofferson remembered.

But “cool” often comes with a cost. Because to pump out clever titles — “The Last Word in Lonesome is Me,” “Some Hearts Get all the Breaks” — Miller carried a briefcase of pills. Amphetamines were “a snake pit I fell into.”

Striving to be taken seriously, Miller tried heartfelt songs. “Husbands and Wives” and “Little Green Apples” were hits but they were the last. Songs kept pouring out but were rarely finished, never recorded. “I don’t remember the Seventies,” he said.

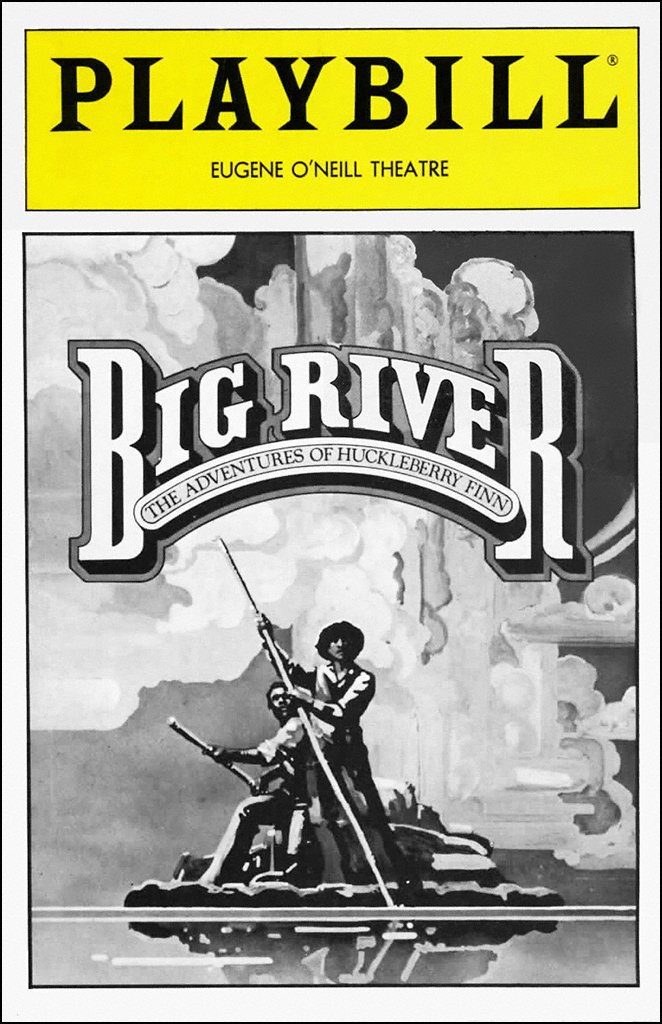

Then in 1982, playing a small club in Manhattan, Miller was approached by a Yale drama professor who “thought he was an absolute genius.” Rocco Landesmann had an idea for a musical based on Huckleberry Finn. Miller had never read the novel, but when he picked it up, “it was all there. I was amazed to find that it was written in the same everyday conversation that I grew up talking." Soon “I was writing from every corner of my heart.”

In April 1985, “Big River”opened on Broadway. The show won seven Tonys, including Best Musical Score for Roger Miller.

Redemption led to more records, but his revival was short-lived. A lifelong chain smoker, Miller died of lung cancer in 1992. He was 56. Three years later, he was inducted into the Country Hall of Fame. His songs, from the wacky to the poetic, continue to be recorded in Nashville and beyond.

Once asked how he wanted to be remembered, Miller said, “I just don’t want to be forgotten.” He hasn’t been. Roger Miller, Kristofferson said, “is right up there with Mark Twain and Steven Foster, real America originals.”

They tell me you’re runnin’ free

Your days are never blue,

I wish I had your happiness

And you had a doo-wacka-doo.

CLICK HERE TO HEAR SIX BY ROGER MILLER