CRUISIN' WITH DAVID FOSTER WALLACE

FORT LAUDERDALE, FL — MARCH 1995 — The brochure promises a week-long Caribbean cruise. Once aboard the 12-deck m.v. Zenith, “indulgence becomes easy. . . relaxation becomes second nature. . . stress becomes a faint memory.”

Passengers are a homogenous lot. Most from Florida, others from the Midwest, they wear Spandex, “maroon and purple warm-ups, white loafers without socks.” But among them is a kind of stowaway, a young writer headed for “a supposedly fun thing I’ll never do again.”

In the years since his suicide, David Foster Wallace has become a legend of sorts. Known as DFW, his post-modern novels and labyrinthine essays are studied and put on pedestals by readers, writers, hipsters alike.

But when he boarded the Zenith, which he called the Nadir, Wallace was known only to a readers on the cutting edge. And once on board, he took readers on a wild and witty ride into the “dark heart” of the cruise industry.

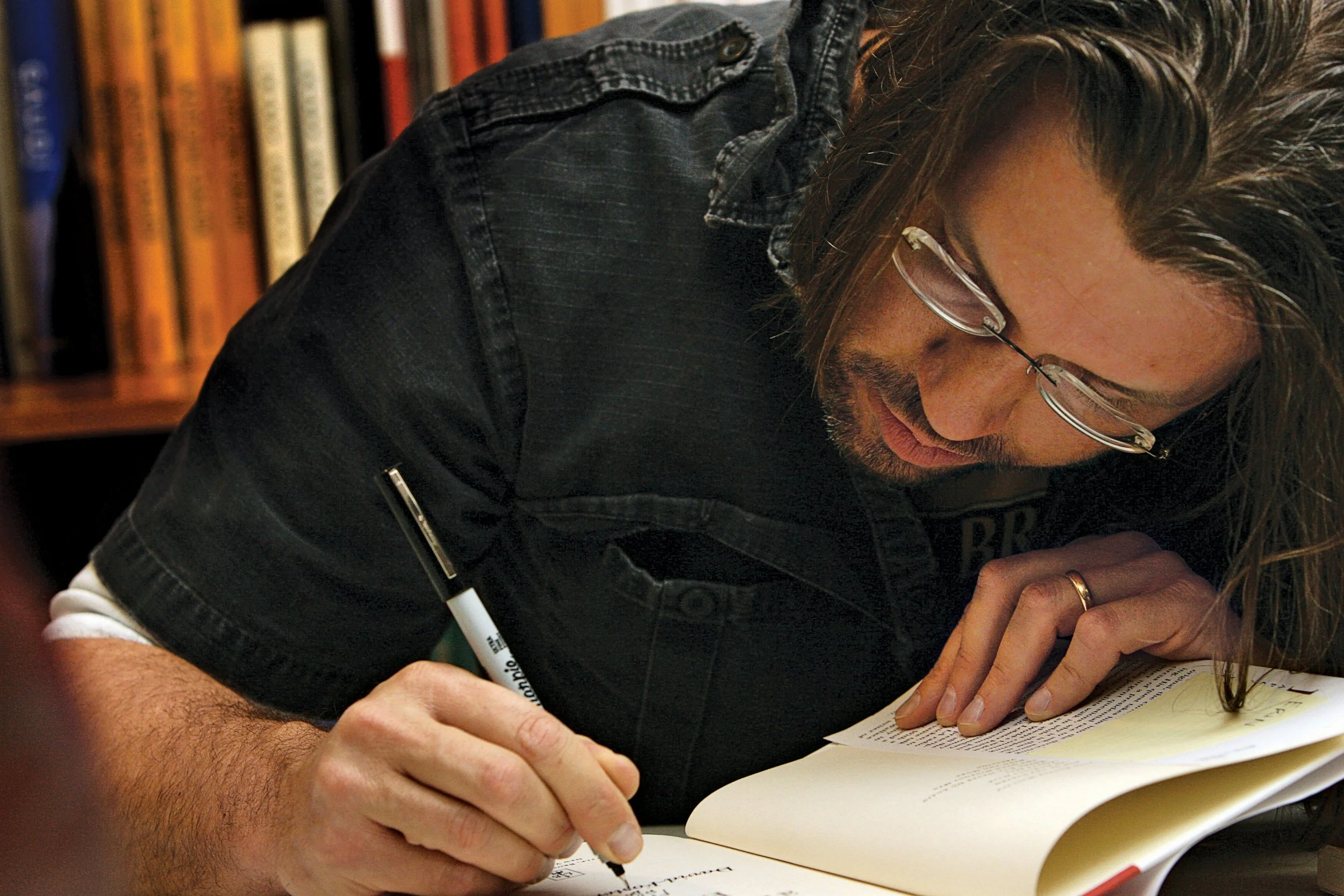

This “tropical plumb assignment” came from a “certain swanky East-Coast magazine.” Having published DFW’s acerbic essay on the Illinois State Fair, Harper’s proposed a cruise article. Wallace, then teaching literature at Illinois State, was not eager to go, at least not alone.

But his friend, novelist Jonathan Franzen, was busy. Others begged off, so during his spring break, Wallace flew alone to Fort Lauderdale. Waiting in line to be taken to the dock, he felt out of place amid all that Spandex. Calling Harper’s, Wallace asked his editor. What, exactly, did he want? “Be yourself,” he was told. “Enjoy. You’ll find the story.”

Before boarding, Wallace wrote to Franzen: “Prospects for an acute and fecund belle-lettristic essay on cruising in ’95 are looking bleak. . . The atmosphere summons images of a floating range of Poconos.” Then the Zenith, aka the Nadir, set sail.

Over the next week, along with “seeing nearly naked a lot of people I would prefer not to have seen nearly naked,” Wallace saw:

“— sucrose beaches and water a very bright blue. . .“

“— fuchsia pantsuits and menstrual-pink sport coats. . .”

“— a woman in silver lame projectile-vomit inside a glass elevator. . .”

The ship’s horn emitted a “shattering flatulence-of-the-gods sound.” The ship itself “was so clean and so white it looked boiled.” The Caribbean’s blue “varied between baby blanket and fluorescent, likewise the sky. Temperatures were uterine. The very sun itself seemed preset for our comfort.”

Wallace, known for binging on Pop Tarts and Diet Dr. Pepper, thought the food “superb.” He developed a crush on Petra, the “Slavanian steward” who could only say “Is no problem” and “You are a funny thing.” He loved his waiter, a squat Hungarian named Tibor, whom Wallace nicknamed “The Tibster.”

Wallace jousted with the Hotel Manager, Mr. Dermatis, nicknamed Mr. Dermatitis, who refused his requests to see behind the scenes. “I wish him ill.” And he recoiled from cruise director Scott Peterson, who “looks like he’s constantly posing for a photograph no one is taking.”

But to a “semi-agoraphobe,” all that pampering was appalling. Each day, Wallace counted “11 gourmet eating ops.” Poolside towels were so thick and lush “you want to propose to them.” His cabin’s vacuum toilet made “your waste seem less removed than hurled from you.”

And then there was the “mysterious invisible room-cleaning.” When he left Cabin 1009 for thirty minutes, the room was cleaned, a fresh mint left on the pillow. Experimenting, Wallace left for 29 minutes, came back. No cleaning. Thirty-one minutes — clean, with mint. How did Petra do that?

Wallace enjoyed dinner conversation with fellow Nadirites, but could scarcely believe what he overheard.

“I have heard upscale adult U.S. citizens ask the Guest Relations Desk whether snorkeling necessitates getting wet, whether the skeet shooting will be held outside, whether the crew sleeps on board, and what time the Midnight Buffet is.”

Wallace said nothing to anyone about his first novel, praised as a “manic, human, flawed extravaganza.” And nothing about Infinite Jest, which after eight years of “daily, fucking war,” was in the final stages of editing.

But you need not plow through that 980-page melange to know that David Foster Wallace dwelled in dire conclusions — about life, literature, even a “supposedly fun thing.”

“There’s something about a mass-market Luxury Cruise that’s unbearably sad,” he wrote early on. And before concluding with a “detailed log of some really representative experiences as together now we go In Search of Managed Fun,” DFW figured it out.

“The dark heart” of any cruise is its promise of ultimate satisfaction. “I want to believe maybe this Ultimate Fantasy Vacation will be enough pampering. . . But the Infantile part of me is insatiable.” From his lifelong battle with depression, he knew that human want persist, demanding another indulgence, another meal, another high. . .

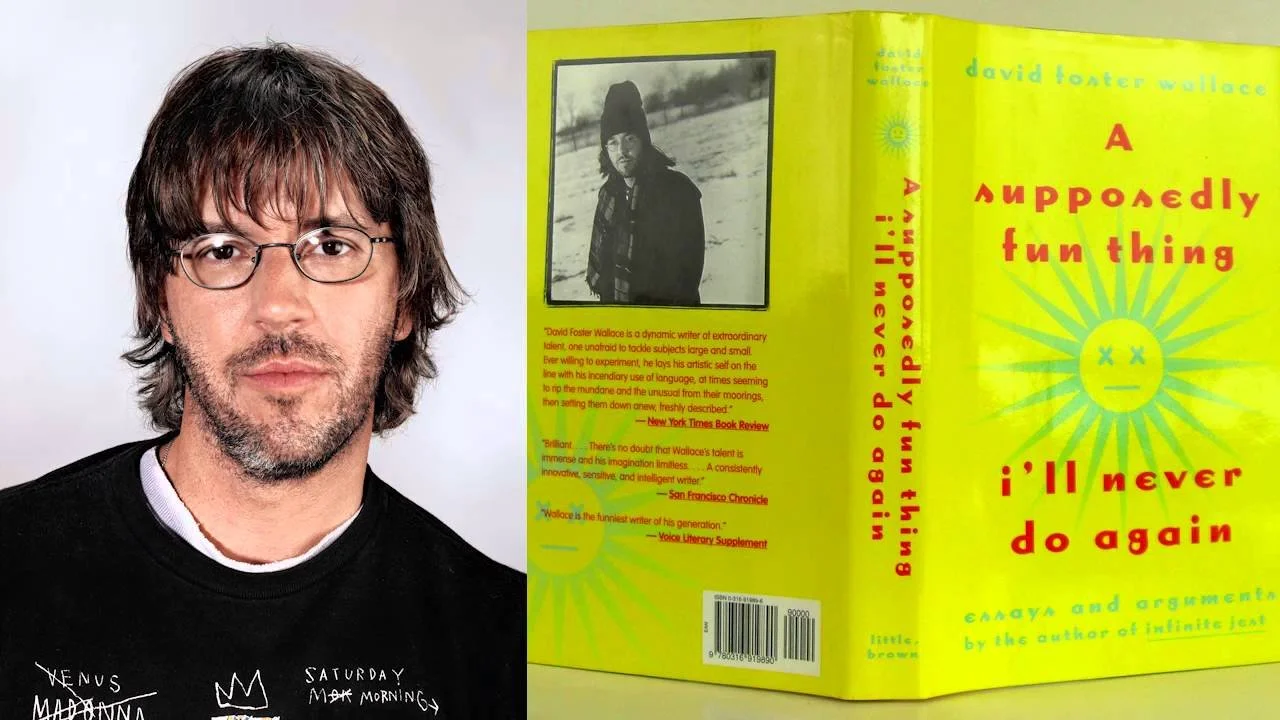

Wallace spent the last two days in his cabin. He began writing his essay while waiting for the plane back to Chicago. Ninety-seven pages, 137 footnotes. By the time Harper’s published “Shipping Out,” Infinite Jest had made DFW “the current ‘It’ boy of contemporary fiction.”

Sold out readings on a nationwide tour. TV and radio. And a fame he never asked for, never wanted. Infinite Jest, hailed as a post-modern classic, remains DFW’s masterpiece. But readers not up for such a slog can sample the style, the razor sharp wit, the manic wordiness in Wallace’s essays.

Wallace’s first essay collection, the New York Times wrote: “reveals Mr. Wallace in ways that his fiction has of yet managed to dodge: as a writer struggling mightily to understand and capture his times, as a critic who cares deeply about ‘serious’ art, and as a mensch.”