GENTLE ON THE RIVER

HOLLYWOOD, CA, SUMMER 1968 — Lights go up. The audience bursts into applause. From their midst, a lean banjo player stands and begins to pick. Behind him, Glen Campbell rises and sings. . .

It’s knowin’ that your door is always open and your path is free to walk. . .

America knows the tune well, is perhaps sick of it. “Gentle on My Mind” was not just a hit, it was cultural wallpaper, quickly recorded by 50 singers from Dean Martin to Aretha Franklin.

But by the time the song became the second most played in radio history, the songwriter, that lean banjo player, had gone home. There John Hartford grew into “a living archive of music lore and the music of the Mississippi.”

Raised in St. Louis, Hartford fell for the Mississippi in fourth grade when his teacher shared her love of riverboats and river pilots. “So instead of studying, I became a dreamer,” he later sang.

A doctor’s son, Hartford accompanied his parents to square dances where fiddlers came out of the Missouri woods to play all night. Old-time fiddle was “the first music I heard that really set me on fire,” and he was soon playing along.

Adding banjo to his toolkit, Hartford went to Nashville, wrote “Gentle on my Mind” in a half hour, and recorded it on his second album.

He considered the song a “word movie.” Glen Campbell considered it “an essay from life.” The Smothers Brothers considered Hartford a fresh voice and invited him to Hollywood to write for Campbell’s summer show. When the show topped TV ratings, Hartford recalled, “all of a sudden it was limousine time.”

Hartford’s laconic drawl and lean good looks won him an offer to star in a detective series. He wanted none of it. “That was a dangerous time,” he recalled, “because you get to thinking not only are you bullet proof but that it’ll go on forever, neither of which is true.” In 1970, he turned his back on fame and went home.

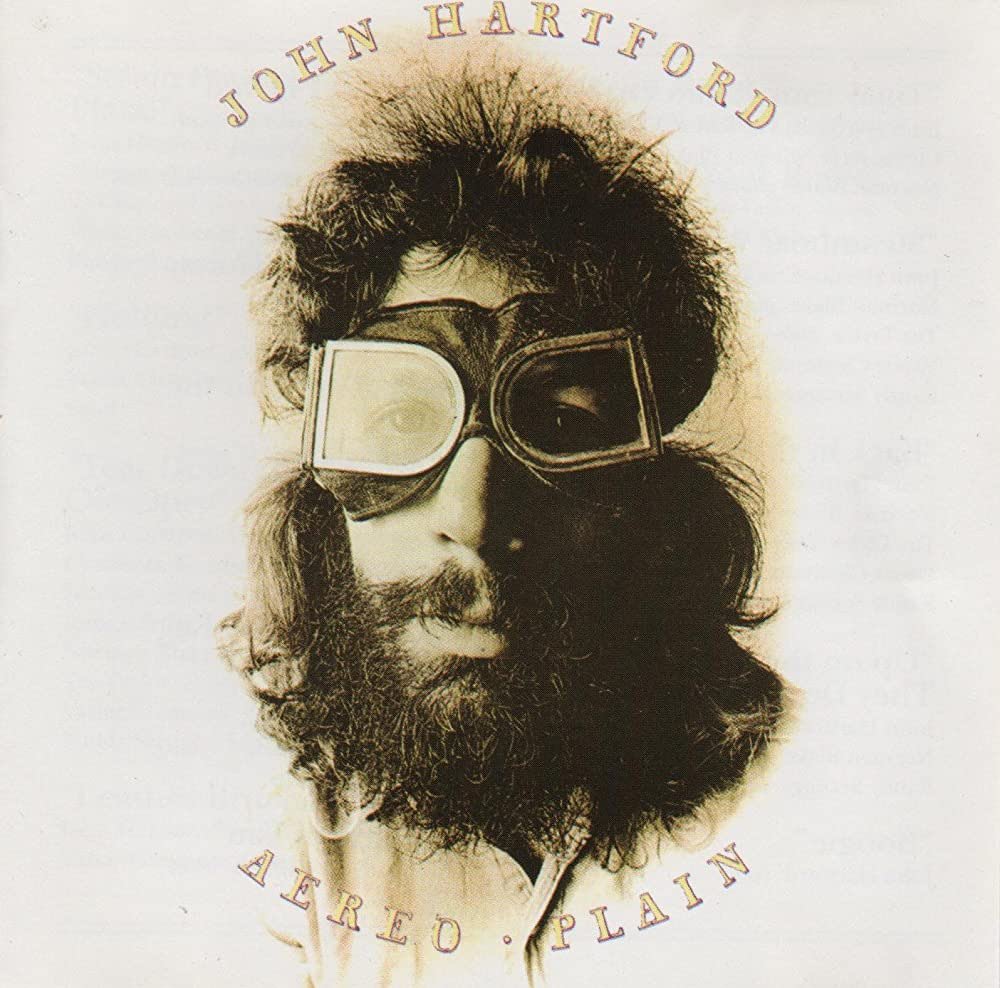

Back in Nashville, Hartford set out to blend his beloved bluegrass with West Coast counterculture. No more “word movies.” Goodbye to the balladeer Hollywood tried to make him. The change was as plain as his next album cover.

“Aereo-Plain” offered a fresh take on old-time music — Newgrass. Backed by Nashville’s top musicians, including the jazzy fiddler Vassar Clements, “Aereo-Plain” captured the fun of an all-night pickin’ session. But John Hartford’s heart was still on the river.

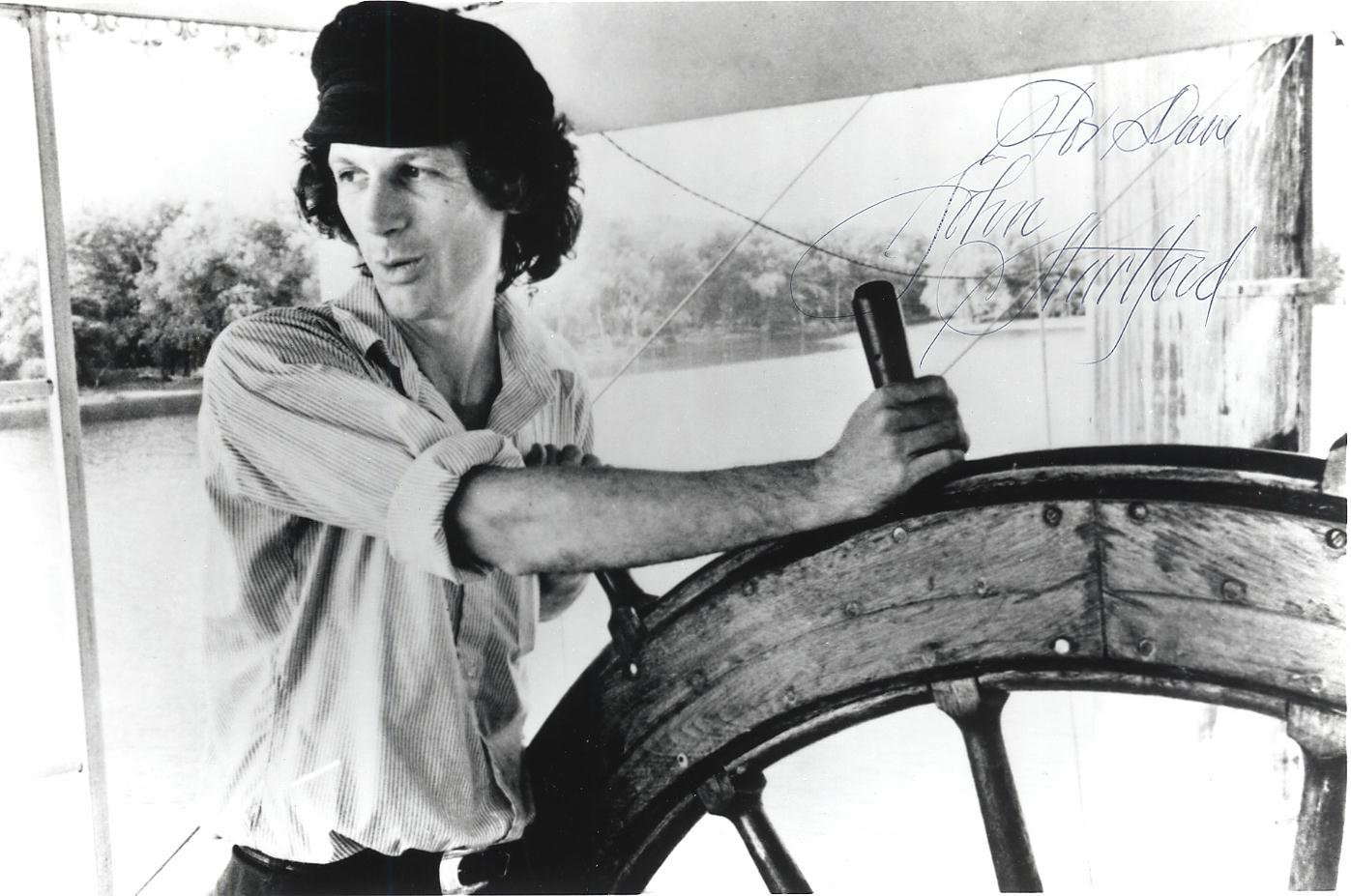

Hartford bought a home overlooking the Cumberland River and added an upper deck resembling a steamboat’s pilot house. Then he went to back to the “Father of Waters” and became a licensed steamboat pilot. Working on towboats and piloting the Julia Belle Swain, Hartford began soaking up river lore. It soon seeped into his songs.

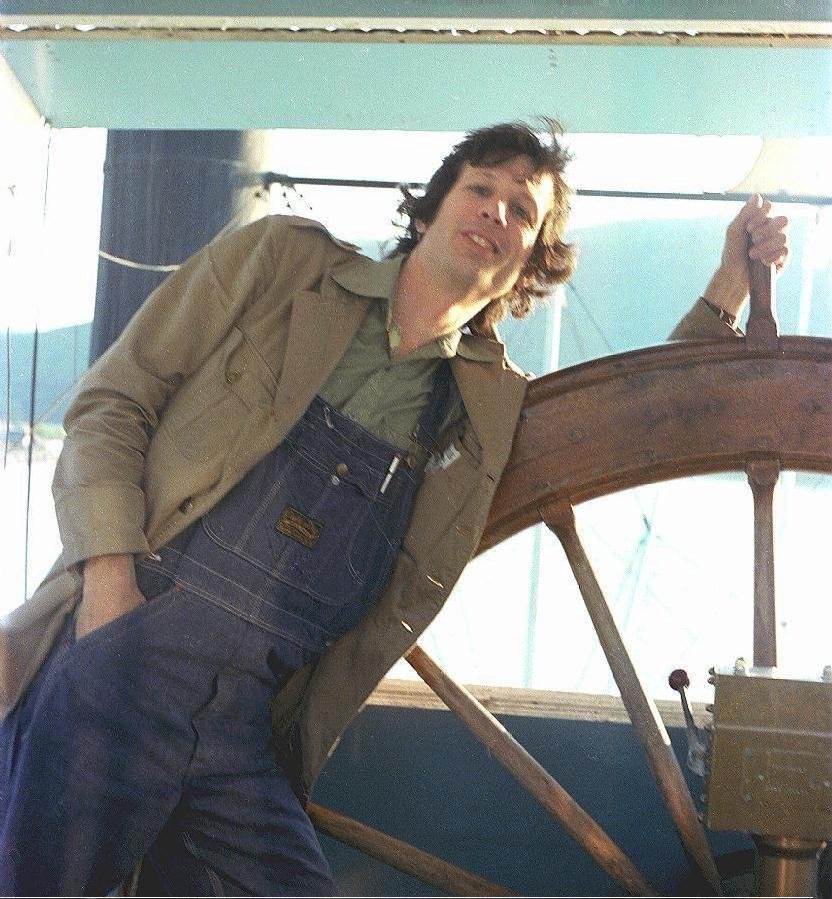

His 1976 album “Mark Twang” drew no limos, no hit parades, but a river ran through it. One day, slowly turning a pilot wheel, Hartford explained: “My life in music has been a steady thing of trying to teach my hands and my feet and my mouth to reproduce the sounds that I hear in my head.”

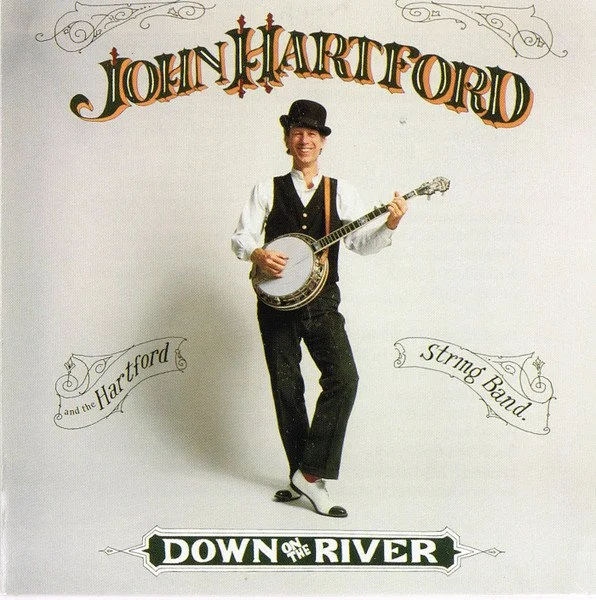

Master of fiddle, banjo, and guitar, Hartford also played his face, slapping cheeks to make melodies. Soon he took his banjo, whose high, lonesome twang was never suited to solo work, and tuned it down seven frets, making a guttural back-up. Finally he taught himself to tap dance while he fiddled. Throw in assorted grunts, whoops, and doodle-dos, and Hartford had a unique American sound. Watch:

Over the next two decades, Hartford was a one-man band. In bowler and black vest, he charmed audiences with sweet fiddlin’, down home banjo, and colorful lyrics.

Hey babe,wanna boogie, boogie woogie woogie with me...

We can boogie over here, we can boogie over there

Come on babe, we can boogie everywhere...

Hartford wrote a children’s book about steamboats and did voiceover in Ken Burns’ “Civil War,” his deep drawl reading Confederate soldiers’ letters. But every chance he got, he went back to the river. There, when not behind the wheel, he played on pilot decks for small groups.

“Working as a pilot is a labor of love. After a while, it becomes a metaphor for a whole lot of things, and I find for some mysterious reason that if I stay in touch with it, things seem to work out all right."

But the music also flowed on. Hartford’s legendary holiday pickin’ parties brought Nashville’s best to play all night. For every tune there was a story, a memory, a word movie.

“John connected not just words to music,” a friend remembered, “but the old days of Nashville to its present, tradition to innovation, newgrass to bluegrass to old-time, television to radio, river to shore, aging musicians to hippies. Goethe may have been the last person to know everything worth knowing, but John Hartford tried.”

Alas, unlike the river, the music could not keep rollin’. In 2001, word spread that Hartford was battling Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. “During the last couple of weeks,” a friend said, “there's been virtually a who's who of musicians who have dropped by to pay their last respects to John. He was probably the most respected musician in Nashville."

A bend in the Cumberland is now called Hartford’s Bend. An annual festival in Indiana remembers him. “Gentle on My Mind” has been recorded by 500+ artists, but Hartford wrote his own epitaph in a song.

Where does an old time river man go

After he's passed away?

Does his soul still keep a watch on the deep

For the rest of his river days. . .