THE DUNE SHACKS OF PROVINCETOWN

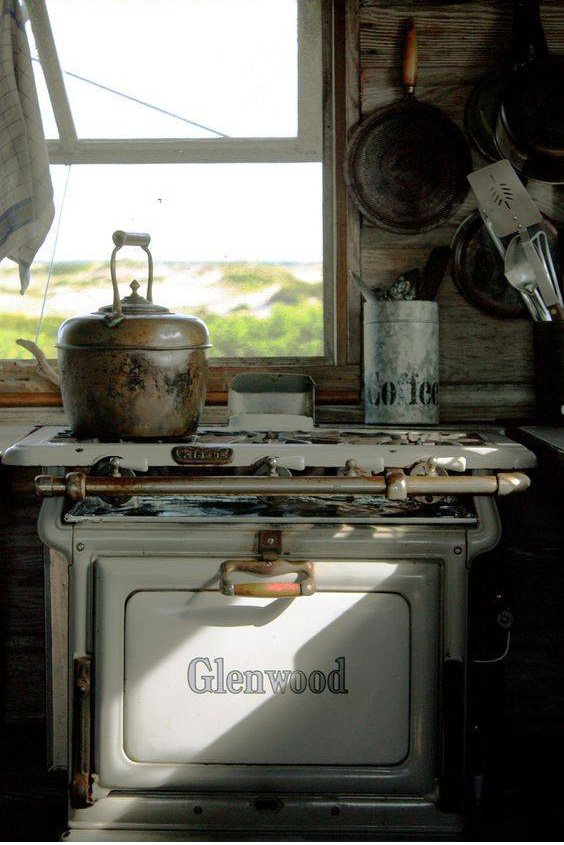

CAPE COD, 1984 — Perched on the edge of America, Dune Charlie lived in a one-room shack on shifting sands. His only companion was his dog, Beauregard. His ramshackle home had no electricity, no running water. Reaching so-called “civilization” took a two-mile trudge across the dunes.

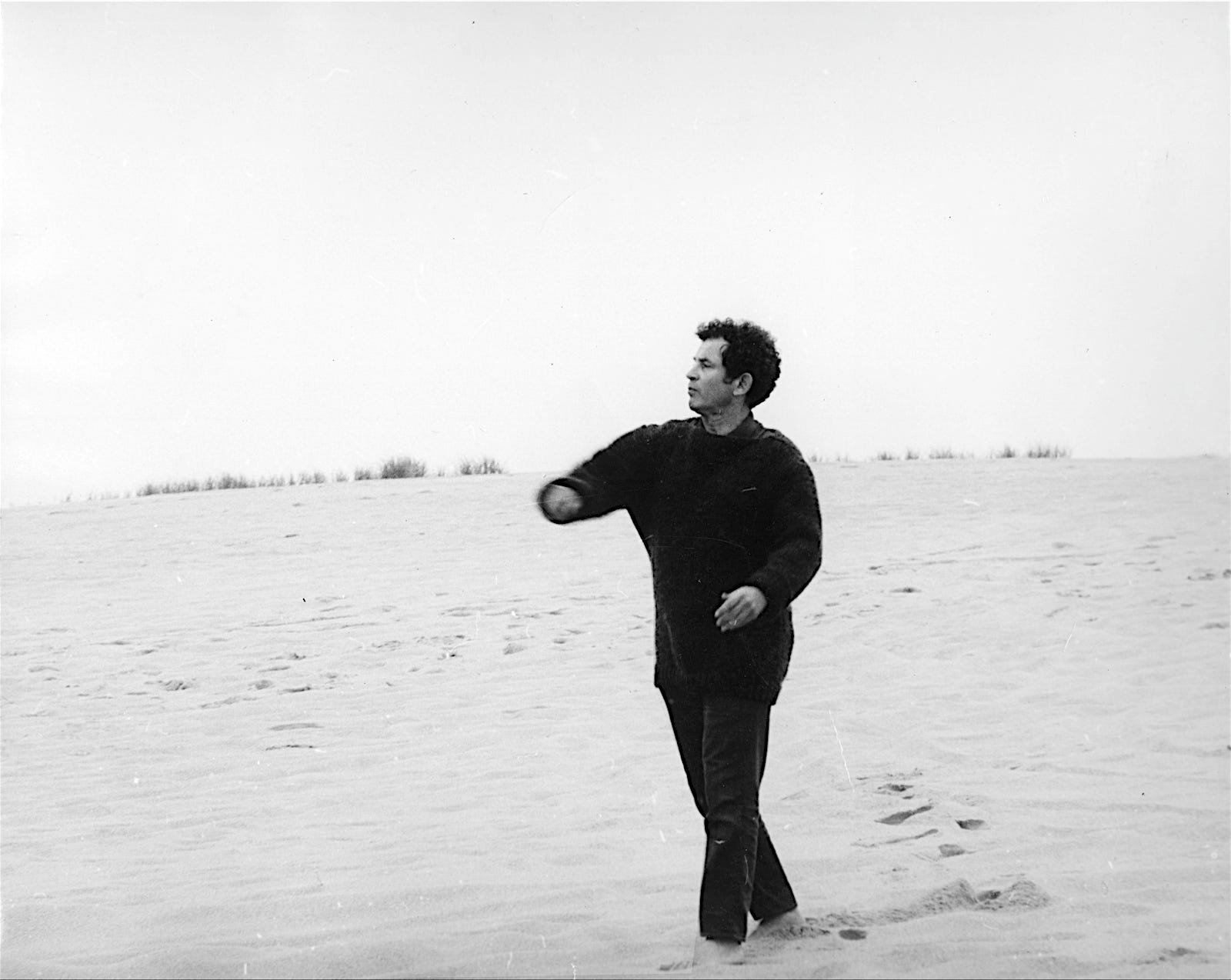

Summers were pleasant but winters tested soul and spirit. Still, Charlie knew the raging sea, the roiling sky, and the sublime sense of escape that Thoreau described in Cape Cod — “A man may stand here and put all of America behind him.”

Then in 1984, after decades on the dunes, Charlie Schmid died. A few days later, the National Park Service bulldozed his shack. Locals in nearby shacks saw their fate. Better get “everything lawyerized.”

Five million tourists come to Cape Cod each summer, but the dune shacks are not on any tourist map. “The shacks lie just two miles from downtown Provincetown,” the New York Times wrote, “yet are so isolated from its crowds, they might as well be on the moon.”

Scattered across the dunes, nineteen shacks, some just 8 x 12 foot hovels, others multi-room with porches propped on pillars, stand like citadels against the onslaught of modernity. A dozen have regular summer occupants. The remaining seven host two- or three-week residencies granted by lottery or short-term rental. Over the years, all have become, one resident said, “like old people you admire.”

Since the Pilgrims made landfall here in 1620, this outer reach of Cape Cod has preserved what they found here — “a wild and savage hue.” In 1882, when the Coast Guard built the first shacks to house rescue teams, one rescuer wrote, “A more bleak or dangerous stretch of coast can hardly be found in the United States.”

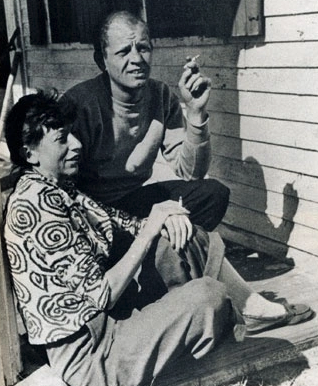

But bleak and dangerous stretches have always called to artists, poets, and writers. Provincetown, with its end-of-the-earth ethos, already hosted such Bohemians. In the 1920s, led by playwright Eugene O’Neill, a coterie of the cultured crossed the dunes to buy or build new shacks.

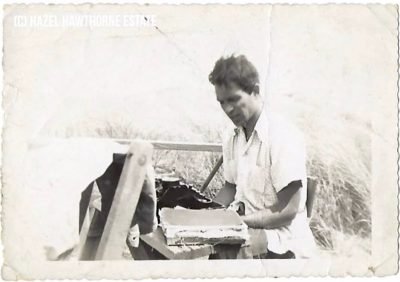

O’Neill found “a grand place to be alone and undisturbed.” Others agreed. Jack Kerouac wrote part of On the Road here. Norman Mailer, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, e.e. cummings and others also sought their muse on these sands.

Bohemians came and went, but as the modernizing world took its toll, a “dune shack society” formed. Starting with “Workweek” each May, some 250 regulars, plus families and friends, repaired winter damage and settled in to savor the isolation Henry Beston described in The Outermost House: “On its solitary dune, my house faced the four walls of the world.”

Most shacks were named for residents but some had nicknames. C-Scape, Euphoria, Frenchie’s, The Grail. Some dwellers kept to themselves, but a hardscrabble life of wood stoves, kerosene lamps, and composting toilets wove a tight-knit community.

“Whether it’s working on your place in a 45-mile-an-hour wind that’s pulling the shingles out of your hand, or just putting the boards up because there’s a gale that has come up all of a sudden. . . that’s part of the neighbors’ deal, what makes them so essential to this whole way of living out there.”

America, however, does not like backs turned away. In 1961, President Kennedy created the Cape Cod National Seashore. The move put all but one shack — the only one with a deed to the property — under government control. Residents were allowed to stay, but park officials saw the shacks as a nuisance. Once Dune Charlie’s shack was razed, could the rest stand for long?

In 1986, shack dwellers formed the Peaked Hill Trust to defend their cherished abodes. Long-time residents collected stories — of O’Neill, Kerouac, and others — to portray the dune shacks as not just quaint but historic. A meeting in Provincetown drew 200 people. Most had never been to the shacks but “just liked that they were there.”

Responding to pressure, the National Park Service divided the shacks into public and private, letting a dozen stay “in the family,” opening the rest to public use. In 2012, the shacks were added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Today, not just artists but architects, designers, scientists, dancers, environmentalists, and others can apply for residencies. Those who don’t win a lottery can rent a shack for a week or more. Prices range from $450 when the winds whip to $750 in summer.

The dune shacks have survived erosion, howling Nor’easters, and government bureaucracy. But this year a new threat emerged when the National Park Service opened ten shacks to long-term leases.

“To treat this intoxicating place like real estate,” said 95-year-old painter Salvatore Del Deo, “I can’t stand the idea.” So far, no leases have been granted, but after a sit-in to defend his shack, Del Deo was evicted. His shack was boarded up. “I imagine that is what it feels like when they nail your tomb shut,” he said.

The dune shacks of Provincetown now face another winter, plus leasing to all comers. “This is a living piece of American history,” a 2004 NPS study wrote, “and that’s lost when you just put random people out there.”

With their fate left to the winds, nineteen shacks still stand. “By any natural law,” one resident said, they “should have fallen into the sea long before.” Knowing they are there, with all of America behind them, suggests they always will be, yet the sands, wild and savage, keep shifting.