THE COLD WAR COMES TO VERMONT

CAVENDISH, VT — FEBRUARY 28, 1977 — Another bitter winter, another annual town meeting. Hearty souls come in from the cold to fill the town hall. Over coffee and donuts, they share gossip, then get down to business.

Budgets. School items. Dog licenses. All in favor? The meeting is almost over when a monkish man with a bald pate and scraggly beard rises to speak. In Russian, with an interpreter.

“аждане Кавендиша! Дорогие соседи!”

“Citizens of Cavendish! Dear neighbors! I have come here today to say hello. . . “

Nestled in the Green Mountains, Cavendish (pop. 1,246) was not on the way to anywhere. The staples of Vermont villages — churches, a general store, maple syrup — were its calling cards. Then without warning, Nobel laureate Alexander Solzhenitsyn moved here seeking “a tranquil refuge, the kind necessary for creativity in this mad, whirling world.”

Solzhenitsyn’s path to Vermont had been hellish. Born in the USSR in 1918, he grew up a loyal Soviet citizen. Inspired by Tolstoy, he tried to write novels in the grand Russian tradition. During “The Great Patriotic War,” he fought on the Eastern Front. But in 1944, his letter to a friend criticized Stalin. The friend told “the authorities,” and Solzhenitsyn was sentenced to eight years in “the gulag.”

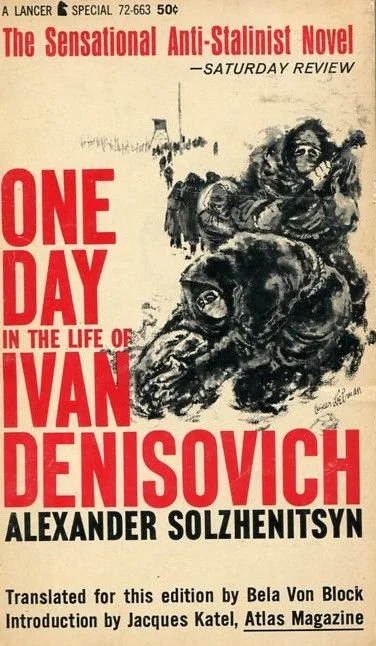

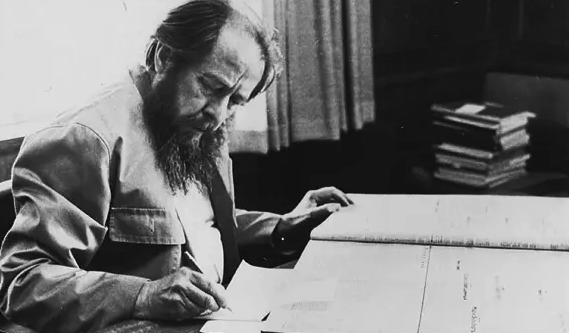

The vast network of prison camps was unknown outside the USSR. Then in 1962, as part of “De-Stalinzation,” Nikita Khrushchev approved the publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch.

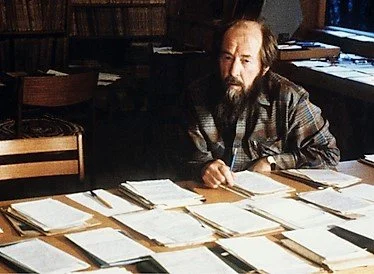

Solzhenitsyn, 44, had grown “convinced I should never see a single line of mine in print in my lifetime.” But his unsparing account of the gulag stunned the world. Suddenly he was famous and, after Kremlin leadership changed, dangerous.

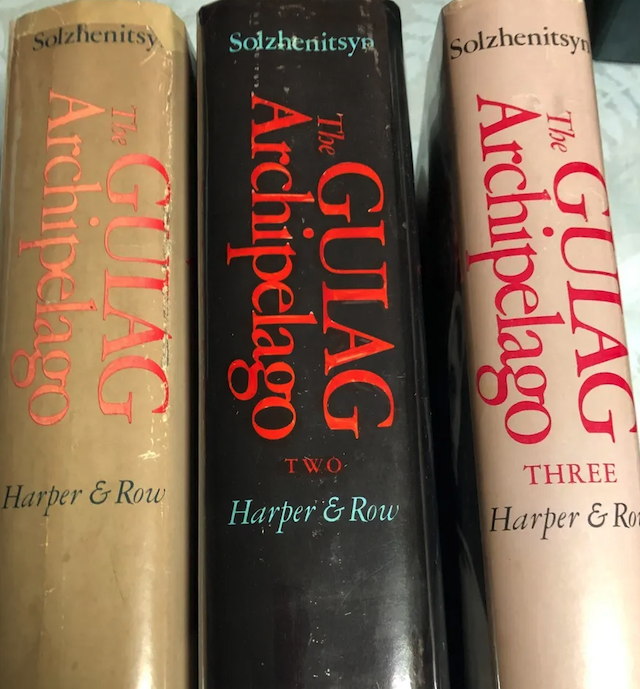

Hounded, stripped of citizenship, his later novels banned, Solzhenitsyn suffered for his belief in an old Russian proveb — “one word of truth outweighs the world.” The KGB poisoned him. The Kremlin accused him of “pathological hatred for the country where he was born.” He refused to renounce his writings, including his massive “Gulag Archipelago.” And once he won the 1970 Nobel in Literature, the whole world was watching.

Finally in 1974, Kremlin leaders decided to banish Solzhenitsyn. And “in a whirlwind of just a few hours” he was deported to West Germany. He moved on to Zurich but was hounded by the press and haunted by the KGB. Where he could he find peace?

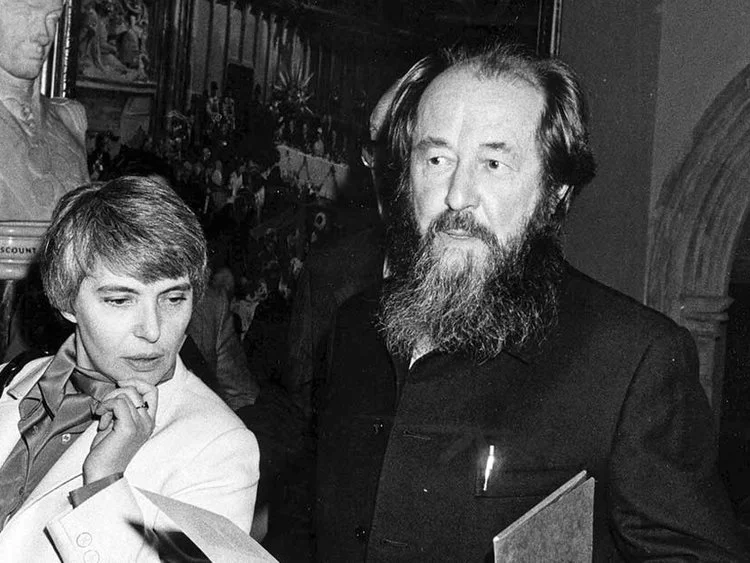

Solzhenitsyn and his wife considered Canada, but despite “proper winters,” it seemed “boring. . . Like a pillow.” Touring New England, they chose Cavendish for remoteness and its proximity to Dartmouth College where Solzhenitsyn might do research.

In September 1976, “happy to have hoodwinked the KGB,” Solzhenitsyn and his family slipped quietly into Cavendish. Within days, a media circus descended. Hundreds of reporters. Cameras. A helicopter flyover. Citizens of Vermont, suddenly drafted into the Cold War, fought with their best weapon — Yankee silence. Solzhenitsyn had asked for nothing more.

Speaking to town meeting, Solzhenitsyn praised Vermont’s “simple way of life, similar to that of our Russian peasants.” Forgive him, he said, for building a fence around his property. Understand, he begged, that “my life consists of work, and this work demands that it not be interrupted.”

Cavendish was impressed. “He'd always been a fairly enigmatic person,” said Town Manager Richard Svec, “and him making a public appearance to the local townspeople, that went a long way with the folks."

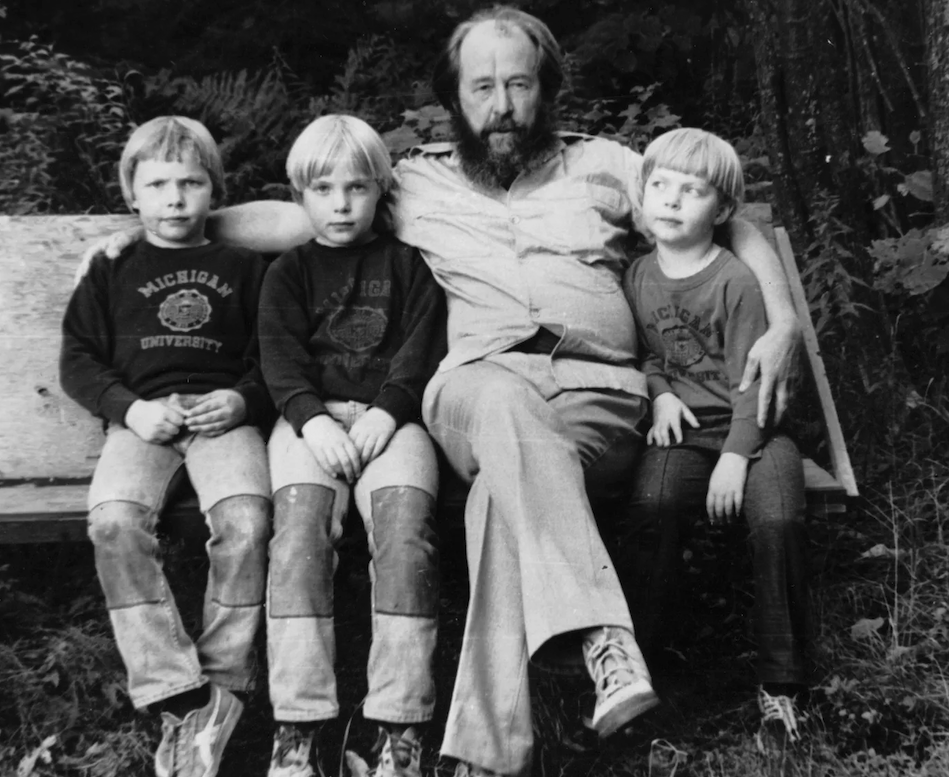

The “dear neighbors” answered Solzhenitsyn’s plea — they left him alone. He settled in to work, writing long into the night.

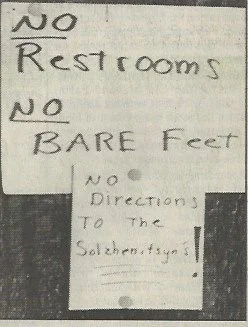

On into the 1980s, Cavendish made Solzhenitsyn a secret all over town. At the general store, a sign read: “No Restrooms, No Bare Feet, No Directions to the Solzhenitsyns.” When asked, kids steered strangers on wayward paths. A neighbor drove Solzhenitsyn’s sons to school. The writer’s wife, Natalya, and her mother became Celtics fans. The local postmaster arranged with Boston authorities to screen his mail for bombs or more poison.

Beyond Cavendish, America besieged Solzhenitsyn with letters, telegrams, requests to speak. In 1978, he made a rare appearance, using hIs commencement address at Harvard to denounce Western culture. “The human soul longs for things higher, warmer, and purer than those offered by today's mass living habits. . . by TV stupor and by intolerable music."

Acerbic and irascible, Solzhenitsyn remained an exile. “Nothing seems the same in a foreign land; nothing seems yours. You feel a constant anguish in those conditions under which everyone else lives normally — and you are seen as a stranger.”

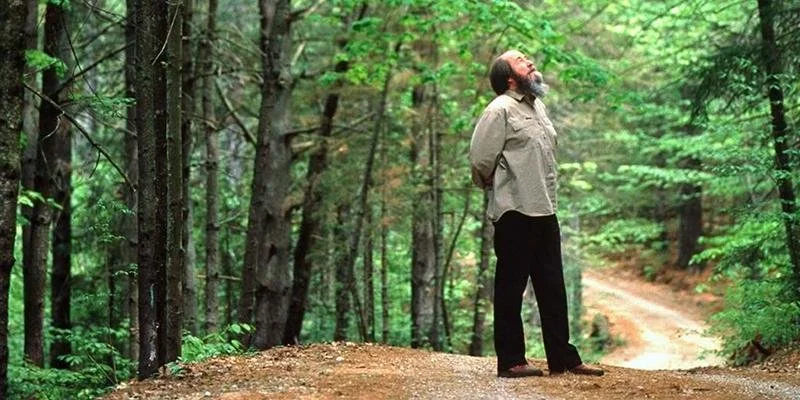

But in Cavendish, he found a home. For 18 years, until the Cold War ended, Solzhenitsyn lived what he considered the best days of his life. Just before his return to Russia, he strolled through Cavendish, enjoying an “enchanting parade.” Again he spoke to town meeting.

“недавно, гуляя по близлежащим дорогам. . .”

“Lately, while walking on the nearby roads, taking in the surroundings with a farewell glance, I have found every meeting with any neighbor to be warm and friendly. And so today, both to those of you who I have met over these years, and to those who I haven’t met, I say: Thank you and farewell. I wish all the best to Cavendish. God bless you all.”

Solzhenitsyn gave signed copies of his books to the local library. Then in February 1994, again flocked by reporters, he left. Two sons, grown up in Cavendish, stayed on to continue their studies.

Russia’s most famous exile returned to live in a dacha outside Moscow. Only in recent years, with the translation of his memoir, Between Two Millstones, did Vermonters read what he had written about them in 1994.

“Farewell, blessed Vermont, so gentle with us! But to stay here, to live out my days here would rob my destiny of its thrust, its spirit. . . I had to get to Russia in time to die there.“

Solzhenitsyn died in 2008. His books are still on display at Cavendish Library.