THE EINSTEIN OF GREEN LIVING

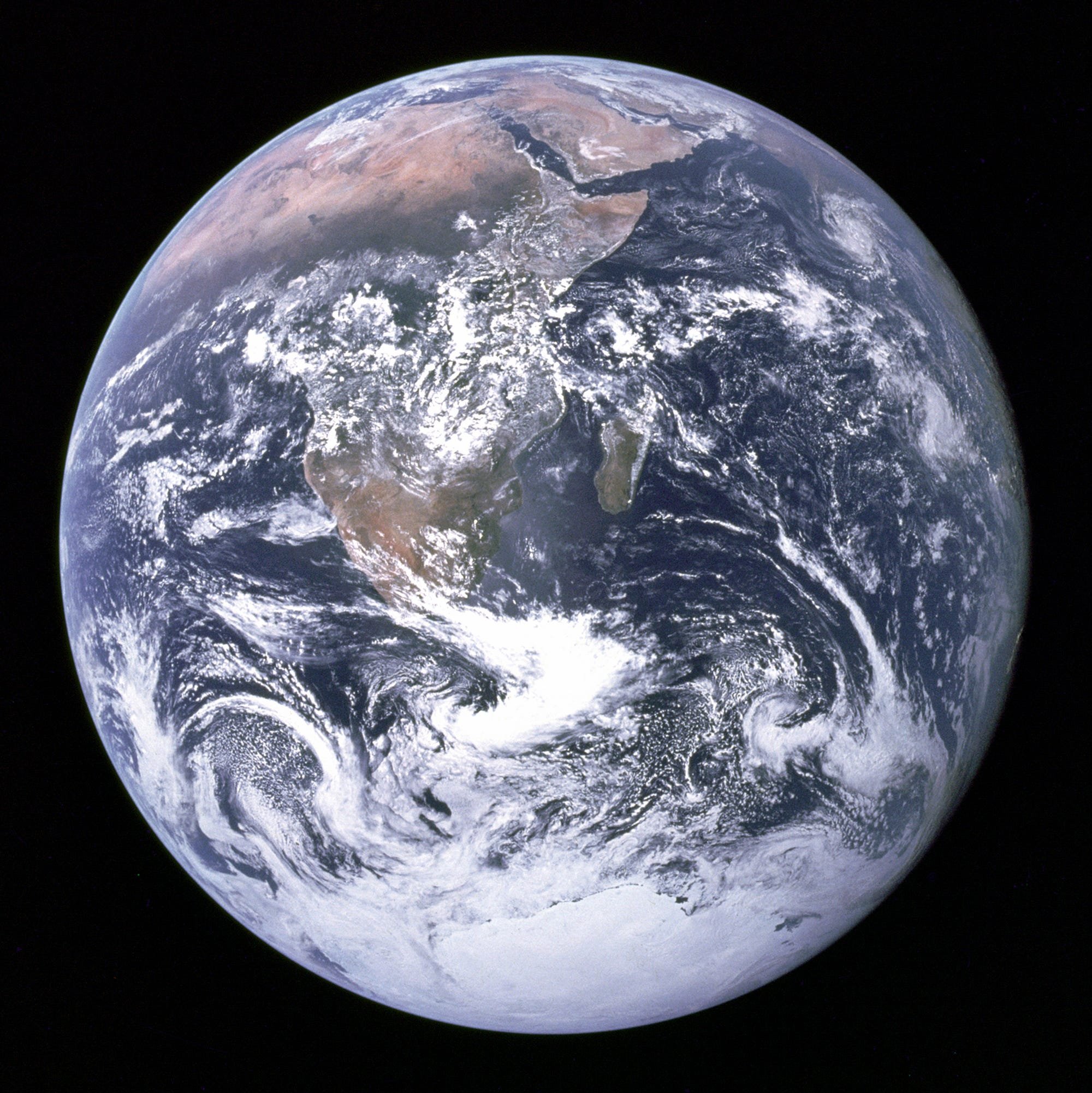

EARTH — 1976 — Energy production has tripled in the last quarter century. Oil companies, still reeling from gas station lines, are pumping out crude. The US uses a third of all energy and nine times more gasoline per capita than the world average. But then. . .

A small man writes a small article in Foreign Affairs. “Energy Strategy: The Road Not Taken” suggests two roads ahead, the “hard path” and “the soft path.”

The hard path is paved with oil, gas, and coal. The soft path uses solar, wind, and hope. Oh, and by the way, our “long-term coal economy. . . makes the doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration early in the next century virtually unavoidable.” This will cause “irreversible changes in global climate. Only the exact date of such changes is in question.”

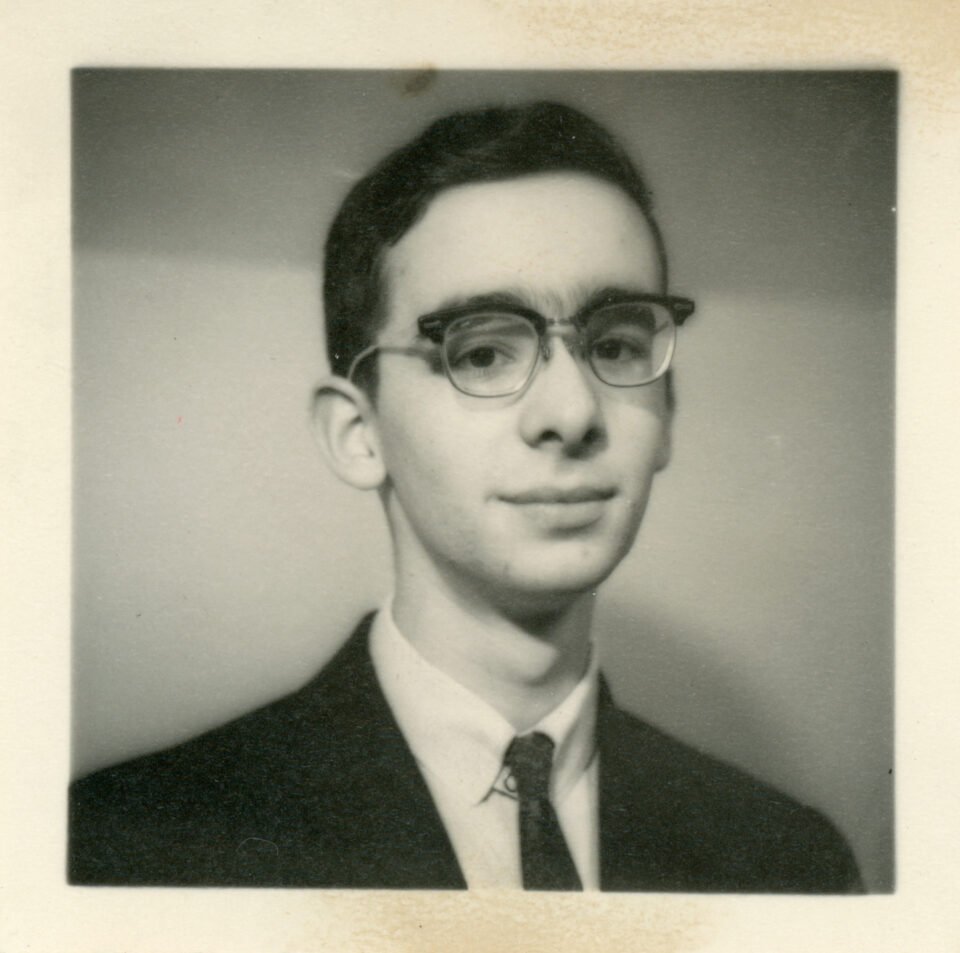

For most of his 77 years, Amory Lovins was a green voice crying in a blackened wilderness. His philosophy — “do less to use less” — was considered naive. “Amory doesn’t understand some of the practical realities of how the world works,” one critic said.

But Lovins has outlasted his critics and alas, been proven right. And today, his Rocky Mountain Institute has grown from a few earnest “treehuggers” into a multi-million dollar consulting firm with 600+ employees teaching entire cities and states, Fortune 500 companies, even the Pentagon to be smart about energy.

“In a room of ten people talking about why it can’t be done,” noted a Wal-Mart executive, “Amory is the one working on the five ways to get there.” Lovins, as economical with words as with energy says, “I don’t do problems. I do solutions.”

Often called “the Einstein of energy efficiency,” Lovins grew up tinkering. Entering Harvard in 1964, he focused on physics, but also studied law and linguistics. When Harvard insisted he choose a major, he left for Oxford.

By the early 1970s, Lovins was in London working for Friends of the Earth. He had written the first of his 31 books and narrowed his interests to one — saving the planet.

“It gradually occurred to me that the problems I was working on, whether they were tertiary structure of proteins or straight physics, were interesting but not very important. . . Because it didn’t much matter how well we understood these other matters if we weren’t here.”

Lovins’ “soft path” article landed DOA in DC. In 1981, the year President Reagan TOOK DOWN THE SOLAR PANELS that Jimmy Carter had proudly put on the White House roof, Amory and his wife Hunter settled in Colorado.

The following year, as Reagan’s Interior Secretary James Watt boasted, “We will mine more, drill more, cut more timber,” the Lovins co-founded the Rocky Mountain Institute in their home on the Western slope.

Led by an Einstein, RMI began calculating energy costs using hi-tech terms. Microgeneration. Data-center design, and worse. But working with Hunter, Amory also coined terms even a CEO can understand.

In 1985, Lovins noticed a typo in a Colorado Public Utilities report. Megawatt written “negawatt.” Lovins made the mistake his own, using “negawatt” to measure energy saved.

Replace a 100-watt incandescent with a 20-watt LED and you’ve created 80 “negawatts.” Lovins envisioned a “negawatt market” based on saving energy rather than guzzling it like pigs at a trough. DC wasn’t interested but by the mid-1990s, a dozen utility exchanges and two states were auctioning negawatts. Energy companies and Energy Star appliances also use negawatts, rewarding thrift with rebates, rate reductions, and lower prices for lower energy use.

Then in 1994, the year after Lovins won a MacArthur Genius grant, RMI introduced the HyperCar. Hybrids were still a decade away, but the Hypercar opened their “soft path.”

With fewer parts, lighter parts, and a hybrid electric/hydrogen engine, the Hypercar promised 300 miles to the gallon. Lovins rejected any patents and put the car’s design in the public domain. Auto makers weren’t interested — yet.

But in 2014, the all-carbon, all-electric BMW i3 became the first Hypercar on the market. Volkswagen’s XL1 followed.

While dreaming up solutions, Lovins gathered up clients. Some green groups only preach to the choir, but RMI, with offices in in Boulder and elsewhere, works with the biggest corporations (and biggest guzzlers). Consulting for Wal-mart, Coca-Cola, Texas Instruments, etc., Lovins angered purists. He scoffed.

“A molecule of oil burned or carbon dioxide released has the same consequences no matter who used it,” he said. None of us wants energy for its own sake. We want warm showers, cold beer, comfortable houses. If we can get those for less, we will.

Yet Lovins knows how many seem immune to hope. After every talk, “someone will get up and give a long riff about all the bad things happening and all the suffering in the universe, which is basically true.” His answer? “Let the person run down after a while and then ask as gently as I can whether feeling that way makes them more effective.”

As critics note, Lovins tends to err on the side of optimism. His high targets for renewable energy often fall short. And then there’s the Jevons Paradox, a gloomy theory that when people pay less for energy, they just use more. Again Lovins scoffs.

“You don’t rewash your clean clothes in the cheaper-to-run washing machine, because your clothes are already clean. At some point, I think you get jaded by continuous trips to Bali.”

So the fight for the planet, pitting cynics against idealists, guzzlers against eco-warriors, rages on. Caught in the crossfire, Amory Lovins argues only for sound engineering, efficiency, and hope.

“You cannot depress people into action,” he says. But “starting with hope and acting out of hope can cultivate a different kind of world."