THE PINPOINT PRECISION OF LIGHT

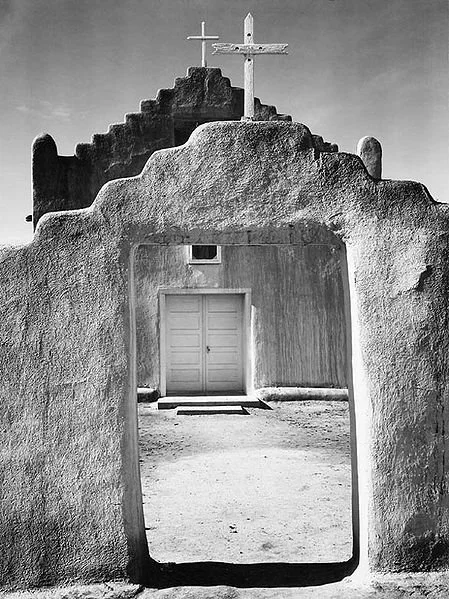

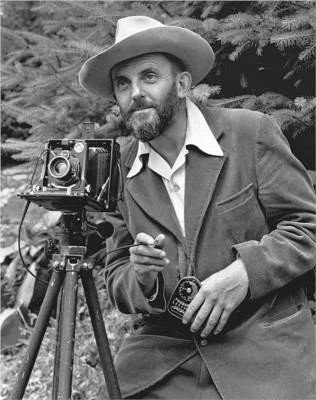

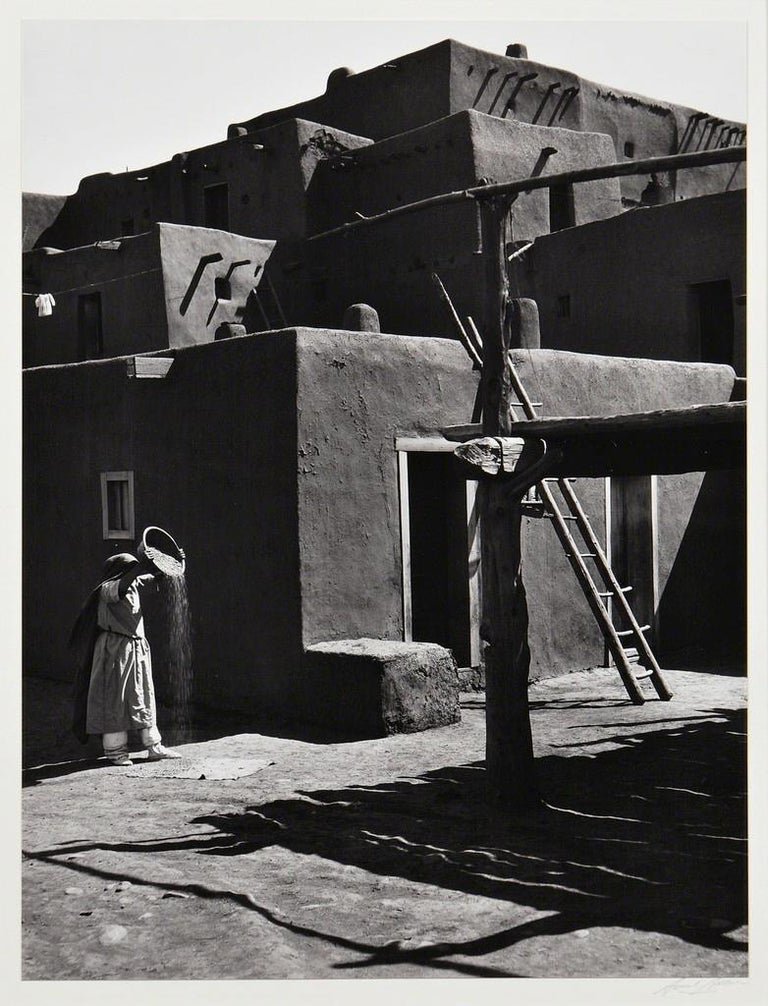

TAOS, NM, FALL 1932 — A blinding stream of high desert light blasts through the plate glass window. After a night of drinking “Taos lightning,” the light seems harsh, painful. Using a sheet of paper to block the beams, Manhattan photographer Paul Strand shows his negatives to a young classical pianist who also dabbles in photography.

“They were glorious negatives,” Ansel Adams recalled. “Full, luminous shadows and strong high values. . . perfect, uncluttered edges and beautifully distributed shapes.” A few days later, Adams went home to San Francisco, “resolved that the camera, not the piano, would shape my destiny.”

Adams’ wife protested — “the camera cannot express the human soul!” “Perhaps,” Adams replied, “but the photographer can.”

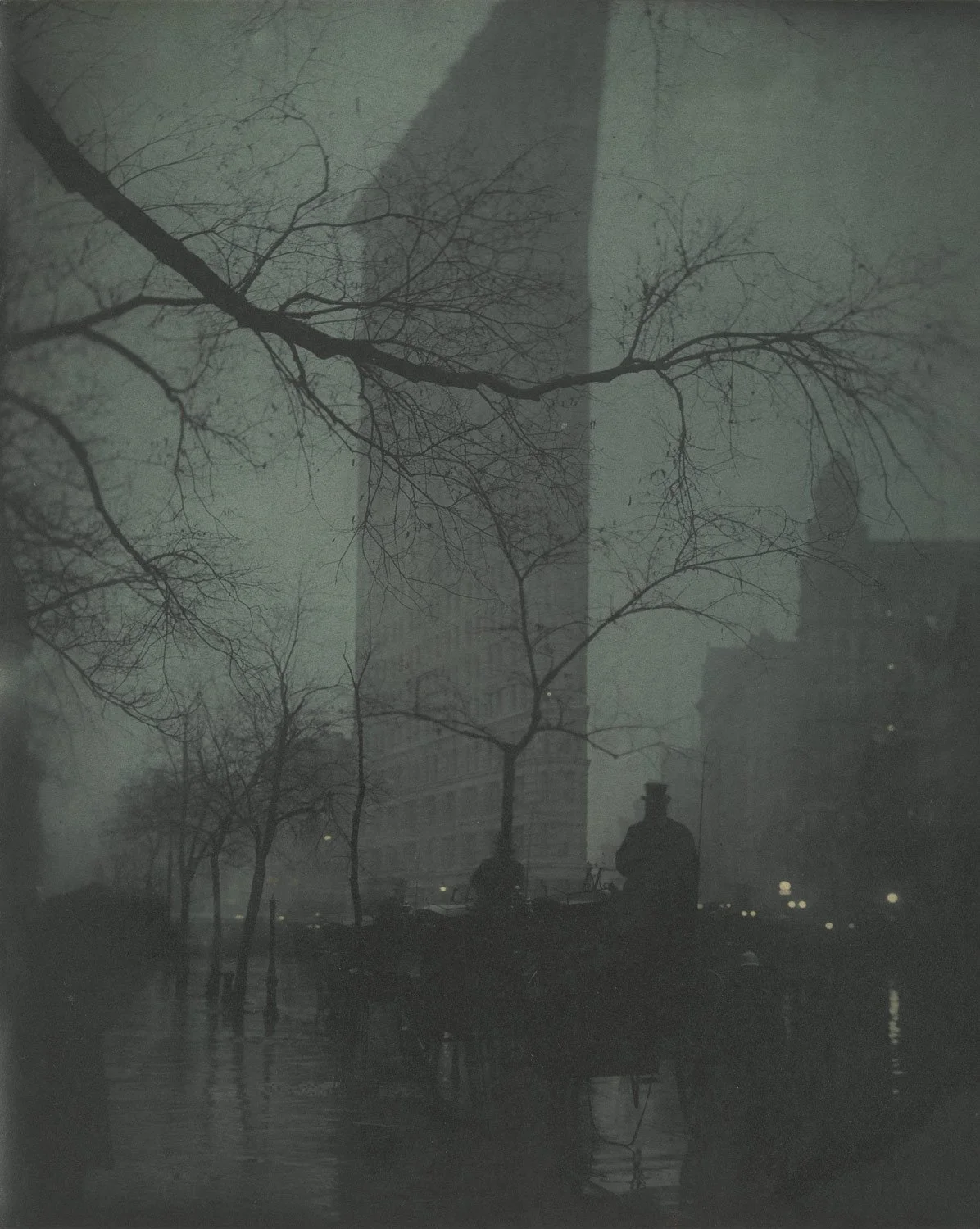

Since 1905, when Alfred Stieglitz founded 291, photography had battled to become Art. Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, and other masters crafted ordinary images into dazzling works of light and shadow, form and beauty. But in the hands of imitators, and amateurs with Brownie cameras, photography was losing its focus. An art historian summed up the scene.

“The decline in the quality of professional work and the deluge of snapshots resulted in a world awash with technically good but aesthetically indifferent photographs." Would anyone stand up for basic black and white?

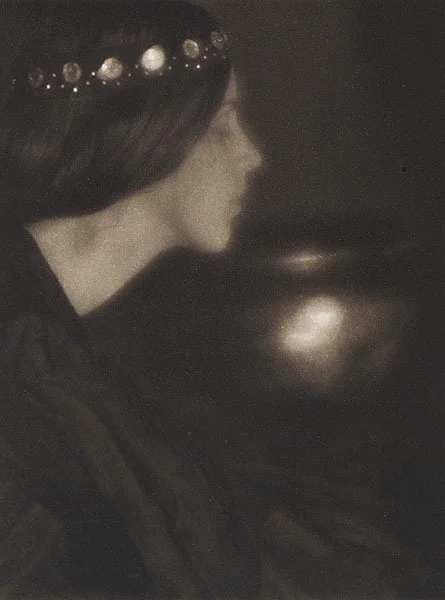

Back in the Bay Area, Ansel Adams met fellow photographers in a barn near Berkeley. Enough of pretty pictures, they declared. Enough of blurred flowers and nudes seen through a lens darkly. Let the Pictorialists make photos that aspired to be paintings. “Pure photography,” should have “no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form.”

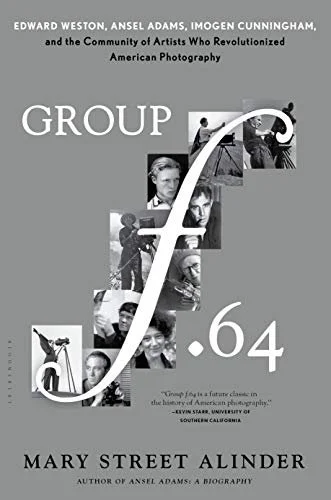

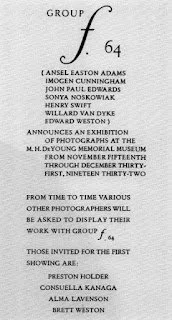

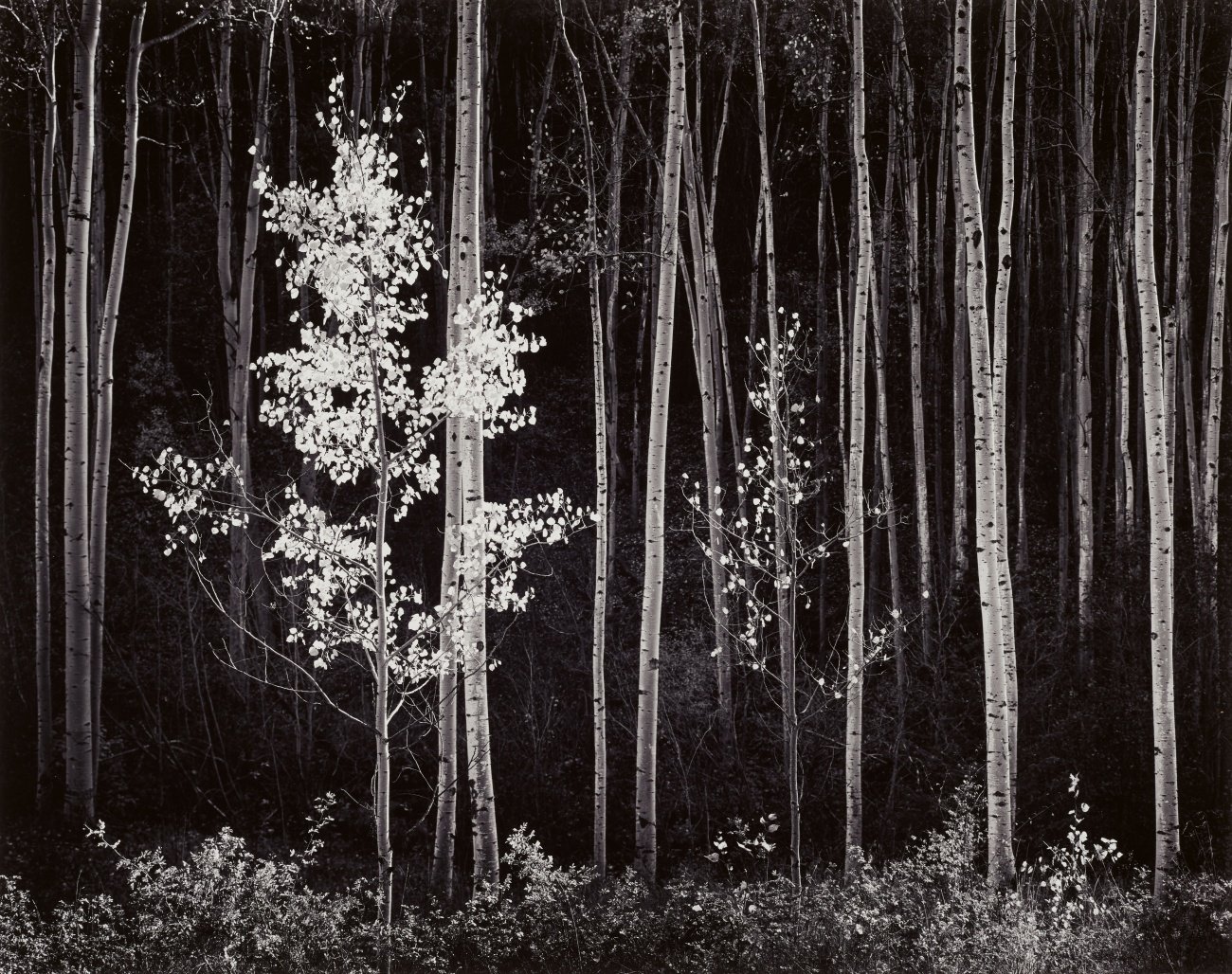

The “pure photographers” chose their name from the camera lens — f/64 — the smallest aperture opening. Seen through that pinpoint, the world was stark, crystalline, and fully focused in a long depth of field. That November, in its debut show at San Francisco’s de Young Museum, Group f/64 began changing how the world and photographs were seen.

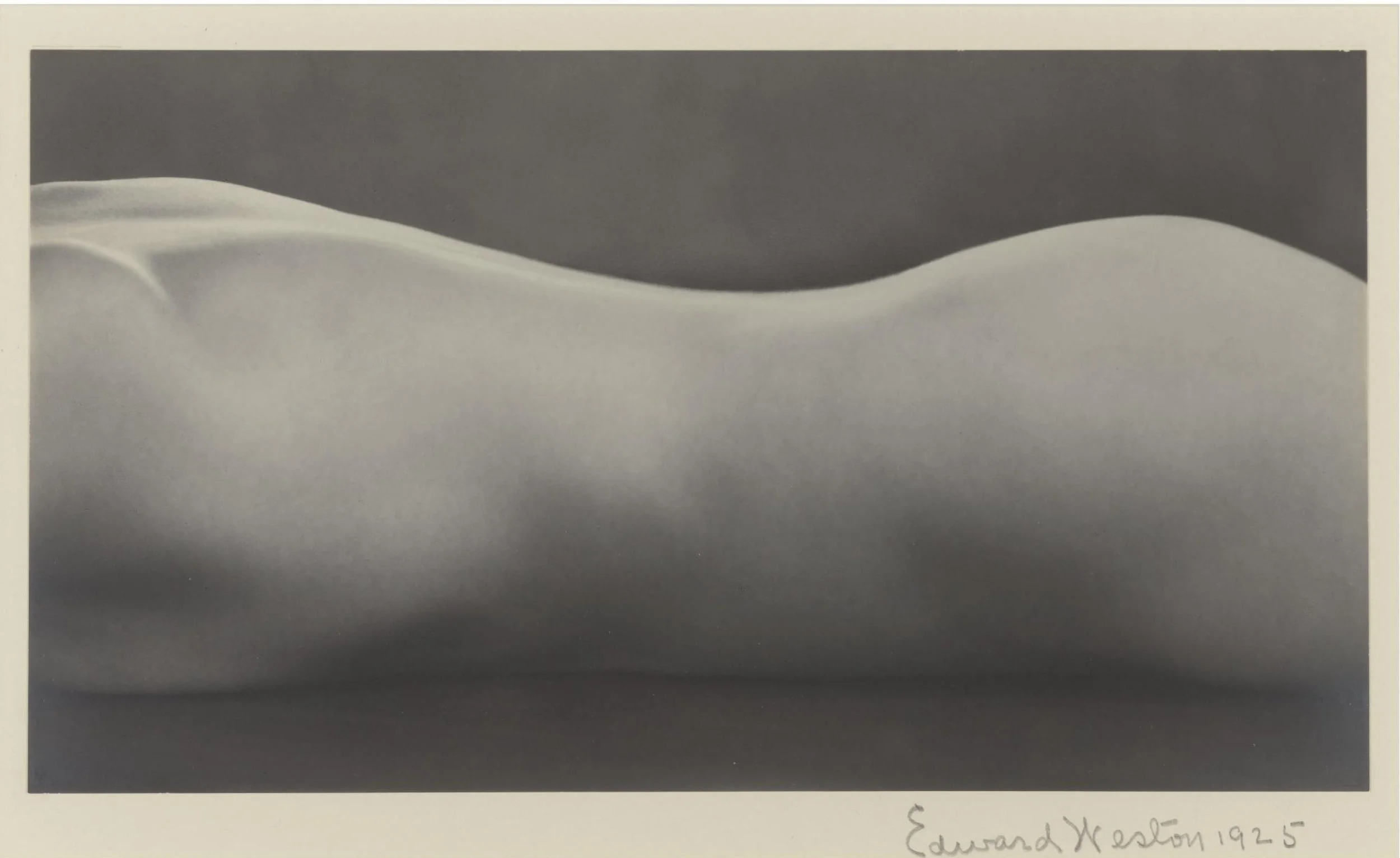

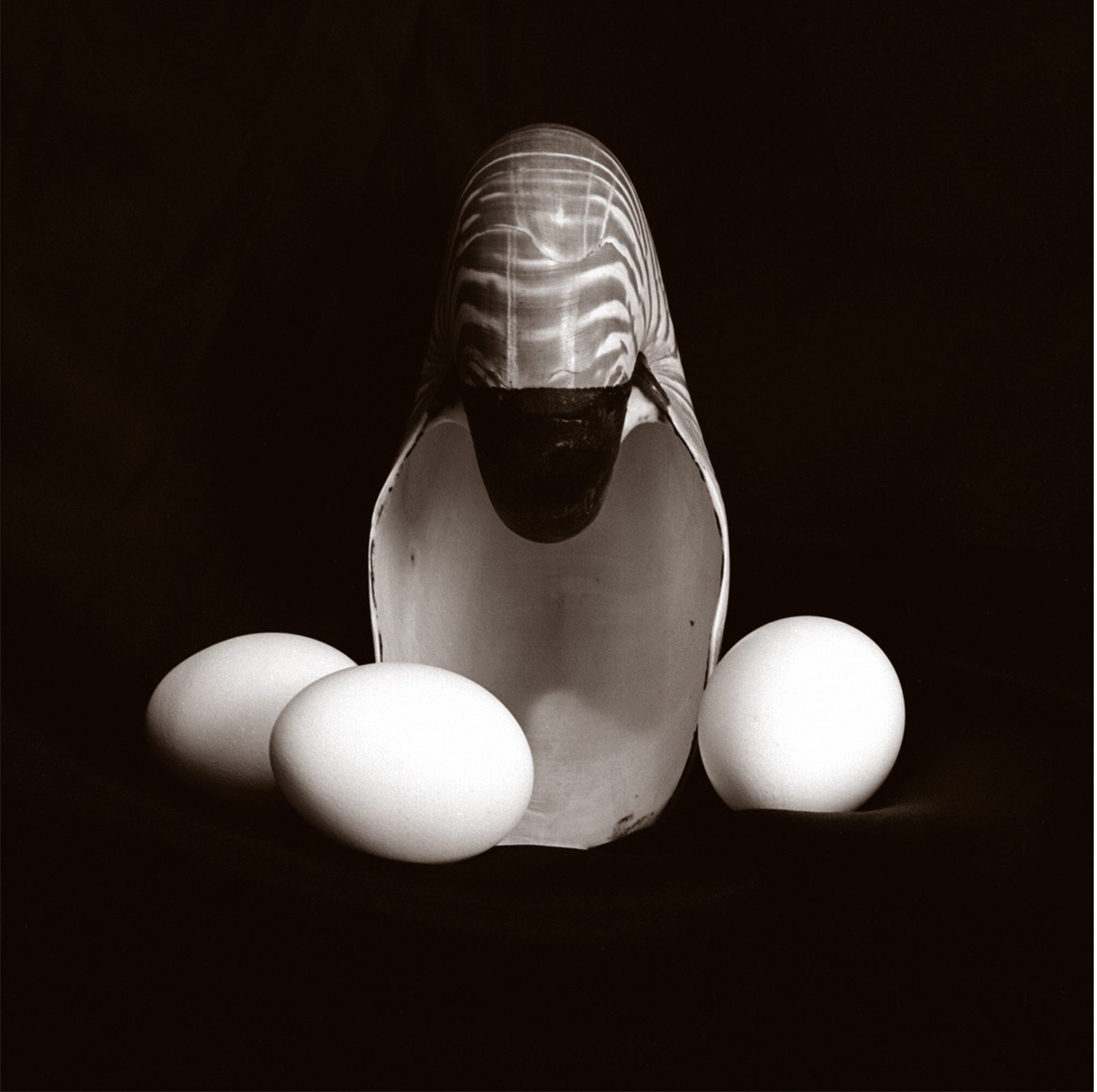

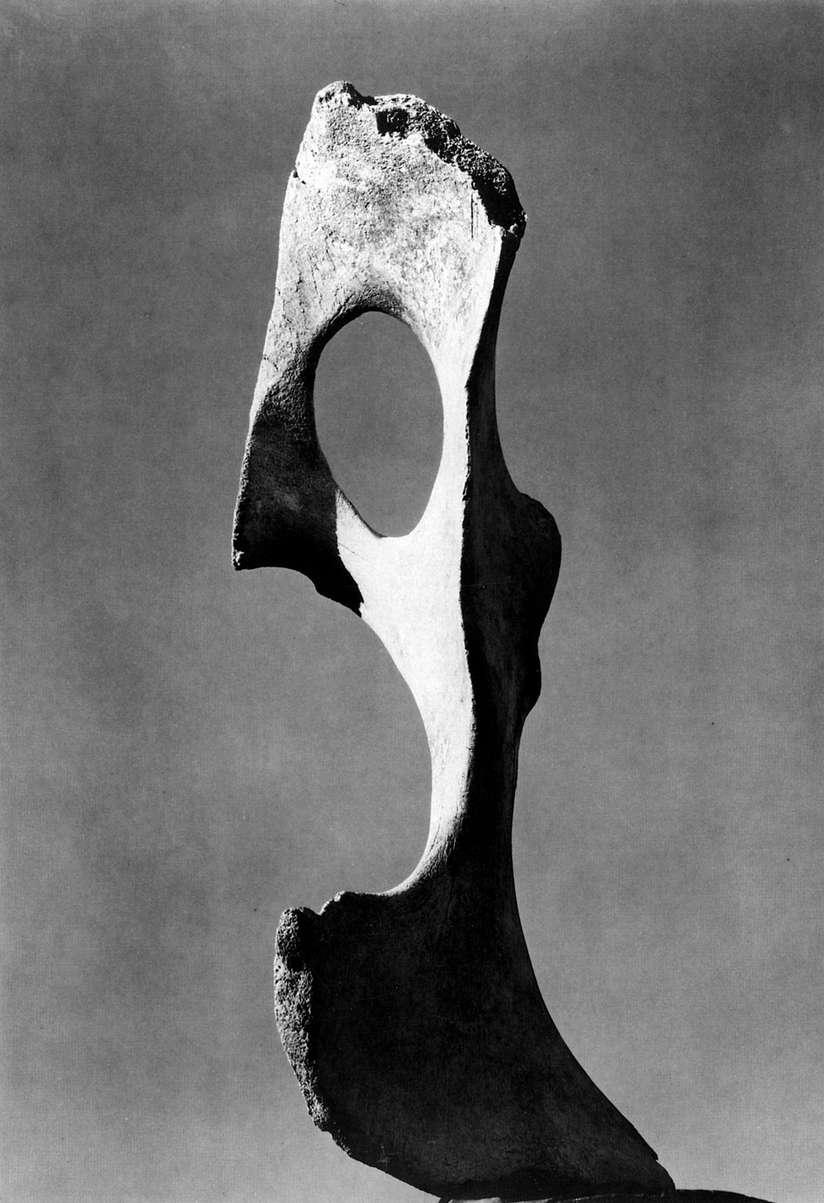

“The camera should be used for a recording of life,” Edward Weston said, “for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh.”

Along with lens and light, the timing was precise. With America flat on its back, eyes were turning West. “Eastward I go only by force,” Thoreau had written, “ but westward I go free.” And throughout the Depression, the West kept the American Dream from going under.

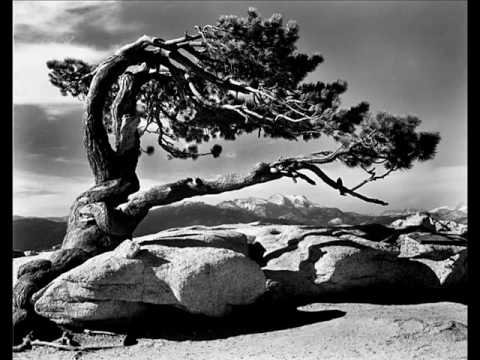

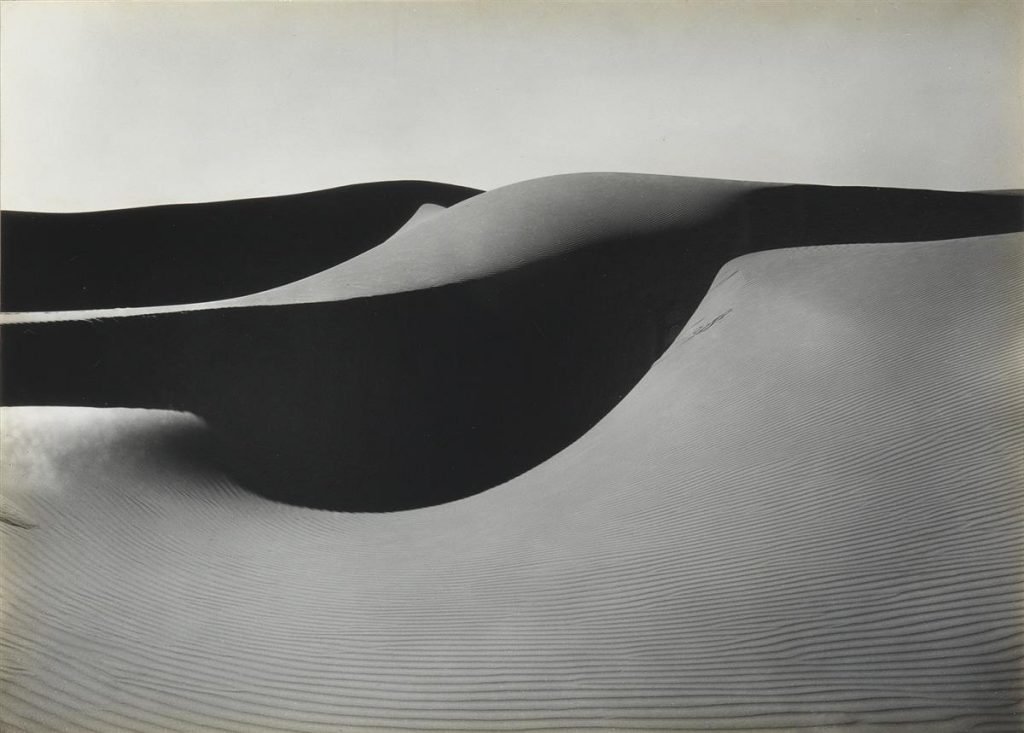

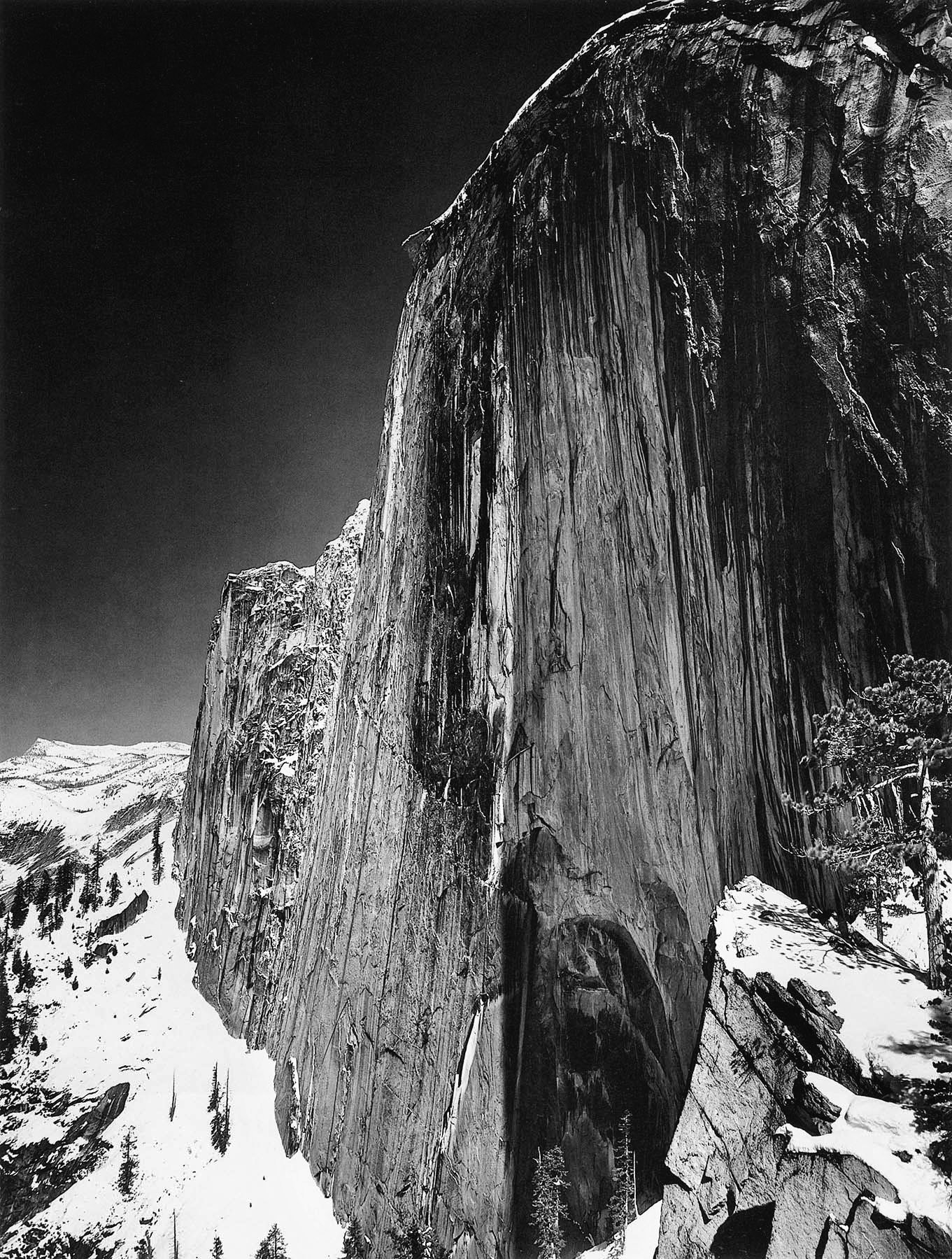

“Okies” piled their lives into old jalopies and fled the Dust Bowl for California. Hoover Dam and the Golden Gate Bridge showed what a downtrodden America could still build. The frontier was closed, the cowboy was gone, but a new West beckoned. Group f/64 traveled into that West — to Yosemite and Yellowstone, across sand dunes and salt flats, and brought back the pictures.

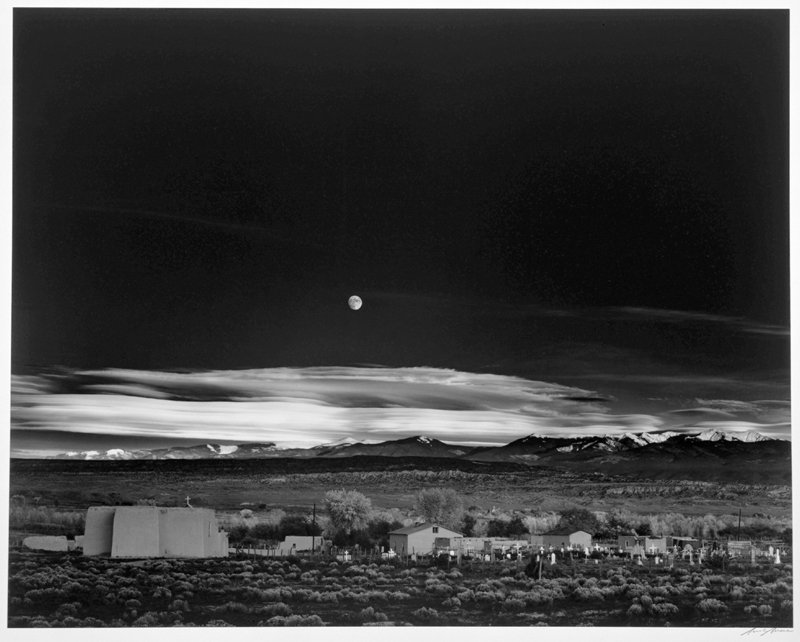

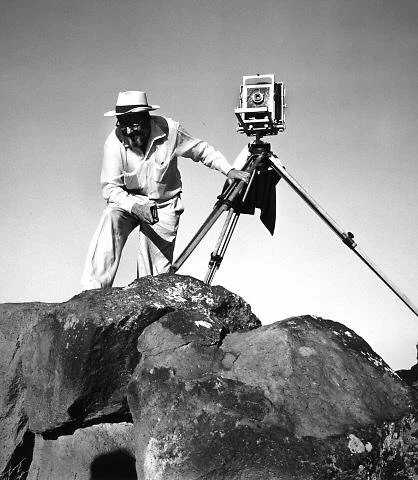

Astonishing pictures. Jaw dropping pictures with Nature as a studio, the moon as a backlight, and shadows stalking every landscape. To achieve their signature brilliance, Group f/64 used huge, bulky cameras. They printed not with enlarging lenses but with contact prints — negatives pressed directly onto paper. And that paper was glossy instead of muddled by matte finishes.

Older photographers scoffed. This was not photography, not art, just shutters clicking. But Group f/64 brought photography into the harsh light of modernity.

Despite sharing a manifesto — “The Group will show no work at any time that does not conform to its standards of pure photography“ — each f/64 member had a unique vision.

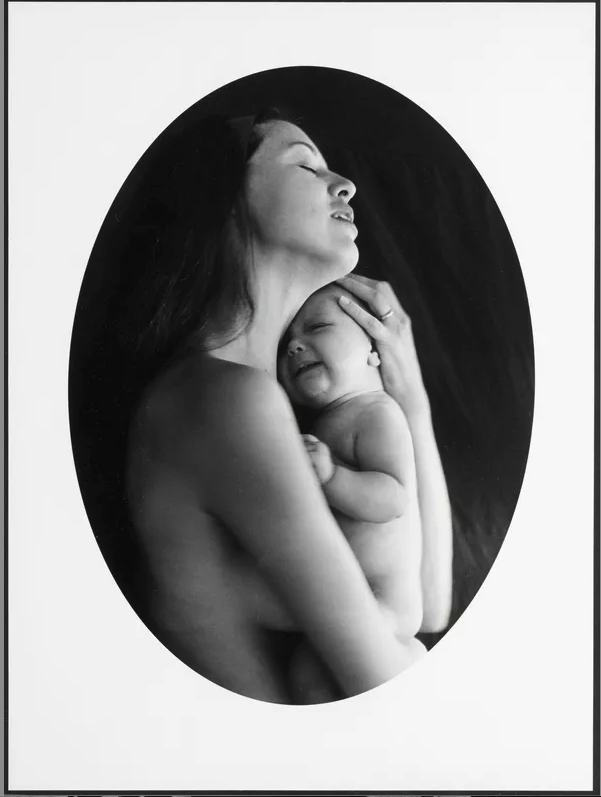

Imogen Cunningham captured the intricacy of plants and the poetry of the human form. Edward Weston saw the world in sand dunes and sea shells. Willard van Dyke captured the “hard brilliance” of bone and sky. Ruth Bernhard let her lens trace the sensual curves of mother and child.

And of course, there was Ansel Adams. Raised in a home overlooking the Golden Gate, given his first camera at 12 during a family trip to Yosemite, Adams used an elaborate zone system and an array of filters to craft light into pure magic.

War and politics soon darkened the world, opening eyes to the socially conscious photos of Dorothea Lange and the battlefield works of Robert Capa. Group f/64 members went their own ways. Adams and Weston were rediscovered in the 1960s when the Sierra Club made their images into calendars and notebooks. The rest of the group had to settle for occasional museum retrospectives.

But even now, in a world awash in photos, where everyone carries a “camera,” the aesthetic of Group f/64 lives on.

“I believe in beauty,” Ansel Adams wrote. “I believe in stones and water, air and soil, people and their future and their fate.”