THE TYCOONS VS. THE NEWSBOYS

QUEENS, NY — July 18, 1899 — All day the news spreads. On busy street corners, in filthy tenements, the boys who shout “Extra! Extra!” are on a hair trigger. That afternoon, a horsedrawn cart stuffed with newspapers pulls into an empty lot. Boys descend on it like locusts. Papers fly. The cart is lifted, tossed, toppled.

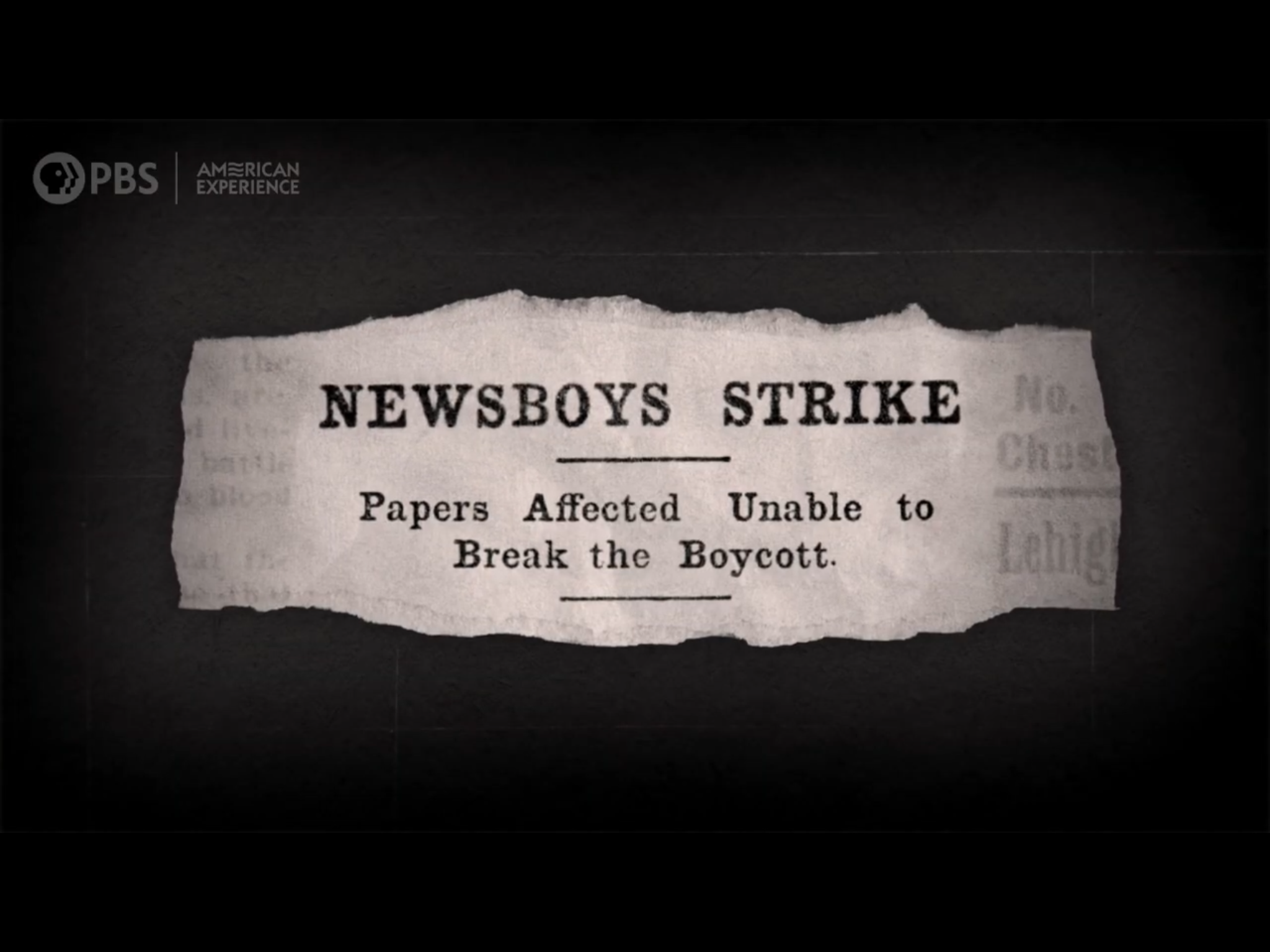

Stop the presses! The newsboys are on strike.

Across an industrializing America, strikes came and went, up to 3,000 per year, but few strikers captured America’s heart like the Newsies.

In 1992, Disney’s “Newsies” featured singing, dancing newsboys. The Broadway musical later won two Tonys. But the truth about the newsboys’ strike, like the truth about child labor, is nothing to sing about.

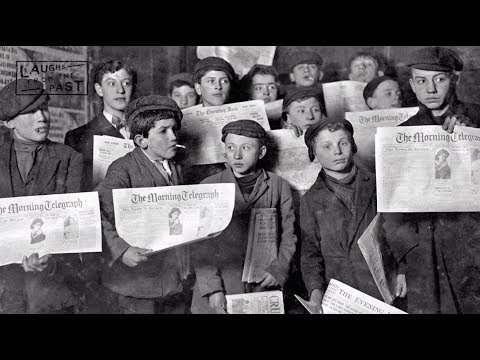

Approaching the 20th century, two million American children toiled in mines and mills. There were few child labor laws, few labor laws at all. (Ah, the good old days!) With child labor yet to be photographed, the Newsies were its poster boys.

Newsies bought papers by the bundle, fifty cents for 100. Selling them at a penny each, a Newsie made about a quarter a day, twice that IF he sold all his papers. Those he didn’t sell, he had to throw away. No reimbursement. Some boys worked until 1 a.m. to make any profit. Then came the war.

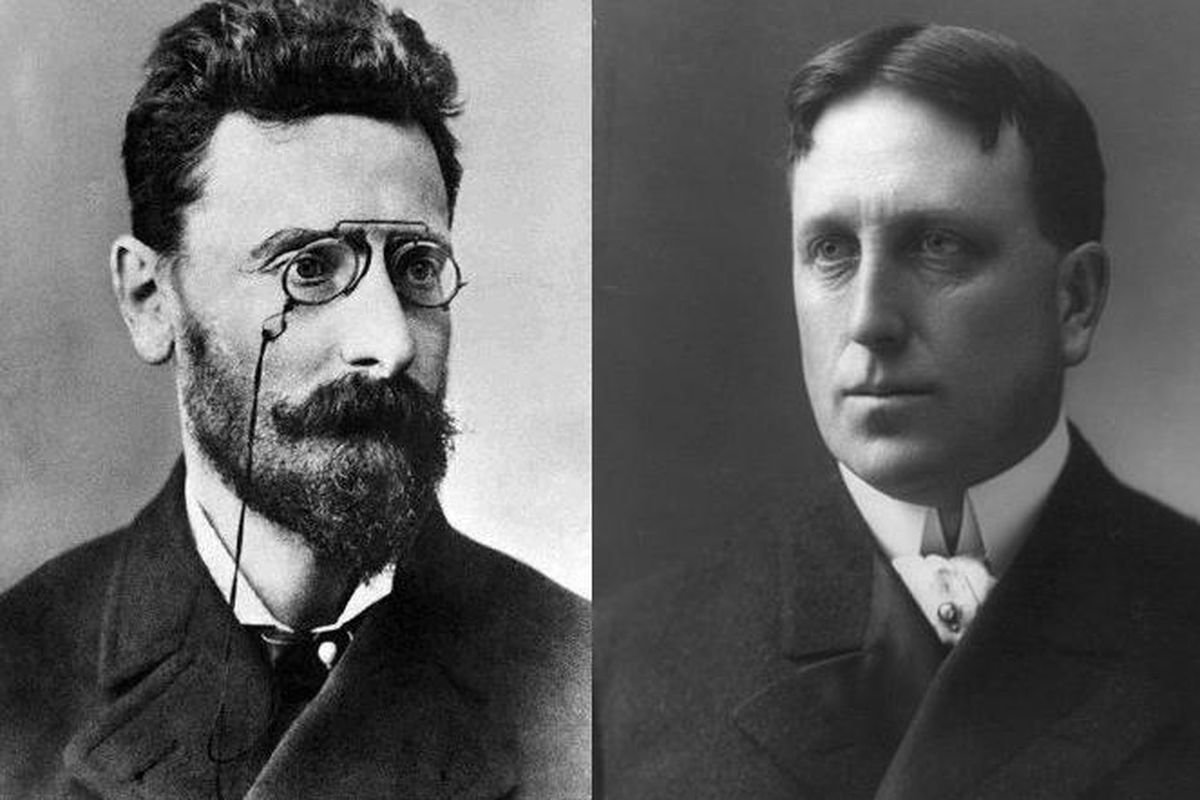

The Spanish-American War sold papers in record numbers. Eager to cash in, publishers upped Newsies’ costs to 60 cents per 100. Strong sales kept newsboys afloat, and when the war ended, publishers lowered the price. All publishers except. . .

Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst were in the thick of war, a newspaper war. New York had fifteen dailies, but Hearst’s Evening Journal and Pulitzer’s Evening World topped circulation. When other papers lowered the cost of a bundle, Hearst and Pulitzer refused.

On July 19, word of the toppled newscart made headline rumors. Five thousand boys marched to Hearst’s offices, shouted, threw rotten fruit, and refused to buy a single paper.

The strike spread like news itself. By July 20, as summer sizzled, newsboys swept along city streets. Spotting a news cart, they swarmed, tore papers out of hands, slashed bundles. Anyone grabbing a loose paper soon lost it. “No true friend of organized labor will read dem papers,” one Newsie said. “We’s got other union papers. Pay a penny and read dem.”

Hearst and Pulitzer hired hulking men to peddle papers, but the Newsies were not deterred. More fights broke out as newsboys attacked “scabs” and sent papers flying.

“You’ll take the bread and butter out of our mouths, you will!” one boy shouted.

New Yorkers chose sides, most siding with the Newsies. Rival papers, happy to challenge Hearst and Pulitzer, gave the strike full publicity. Newsies also told their own story.

Newsboys wore papers pinned to hats and coats. “Please don’t buy the Evening Journal and World because the newsboys has striked.” Newsies reached out to advertisers, asking them to yank their ads. Many did.

Throughout that first week, mayhem continued. Newsies descended on anyone selling the “Woi-ld or the “Choi-nal,” anyone except the few female Newsies. When one man asked why, a boy said, “We’re sorry but we can’t help it. We ain’t fightin’ women.” The man gave the boy a dime.

On July 24, 5,000 boys crammed into Irving Hall for a rally. Local assemblymen backed the boys. “You are only the rising generation,” one said, “and if the older ones can’t support you, they can at least treat you fairly. Now keep up the fight.” But the best speeches came from leaders of the upstart Newsboys Union.

Their names were straight off the street. Young Mush. “Racetrack” Higgins. “Crutchy” Morris. The speaker who won the floral horseshoe for best speech was “Kid” Blink.

“Ten cents in the dollar is as much to us as it is to Mr. Hearst, the millionaire,” Blink shouted. “Am I right? We can do more with ten cents than he can do with twenty five. Is it, boys?”

“It is! It is!”

The strike dragged on. Urged to curtail violence, the Newsies obeyed. Fewer scabs were targeted, fewer papers scattered. Solidarity spread. Soon newsboys from New Jersey to New England were refusing to sell the hated papers. Newsboys in Ohio and Kentucky walked off the job. Even editors were impressed.

“Practically all the boys in New York have quit selling,” a World editor said. “The advertisers have abandoned the papers. It is really remarkable the success these boys have had.”

By August, circulation at the World and Journal was down by two-thirds. Negotiators met with strike leaders, and on August 2, the strike ended. The boys won, sort of.

Hearst and Pulitzer kept their 60 cent price BUT agreed to buy back all unsold papers. A Newsie no longer had to stay out past midnight to break even. Buy 100 papers, sell just 80, sell the rest back, and a Newsie could clear a whopping 32 cents per day. A gold mine.

A decade later, child labor laws, some struck down by the Supreme Court, began to emerge. Yet only the New Deal fixed strong laws in place. Today, with federal inspections curtailed, violations of child labor laws are rising.

“This isn't a 19th century problem, this isn't a 20th century problem," said a Department of Labor official. “This is happening today. We are seeing children across the country working in conditions that they should never ever be employed in the first place."

Sometimes the news is hard to take without the same old song and dance.