HANK WILLIAMS -- SON OF A GUN

OAK GROVE, WV, New Year’s Day, 1953 — Drunk and disheveled, Hank died in the back seat of a sky blue Cadillac bound for his next gig. The heart attack must have been quick and quiet. Driver and passenger thought he was asleep. Two hours and a hundred miles passed before they noticed. He was 29.

This week we celebrate the 100th birthday of one of America’s few human jukeboxes. Our music is replete with songwriters, but only a handful seemed to BE music, to open a tap and let perfect, catchy lyrics and melody flow. Stephen Foster was one. Bluesman Robert Johnson. Leonard Bernstein. Carole King and early James Taylor. And of course, Hank Williams.

Decades after his death it’s hard to believe that all the classics poured from his tap in just five years. Hank had 55 Top Ten songs, including a dozen #1’s. The canon is bound to stick in your head, just from the titles.

“Your Cheatin’ Heart.” “Jambalaya.” “Hey Good Lookin’.” “Cold, Cold Heart.” I Can’t Help it If I’m Still in Love With You.” Many were written in under a half-hour. Most have been covered by singers ranging from Norah Jones to Creedence, from Ray Charles to Elvis to Tony Bennett.

The songs are the unofficial soundtrack of several states. Not just songs, they are lifestyles in verse, with pedal steel backup.

“Almost singlehandedly,” the Country Music Hall of Fame wrote, “Hank Williams set the agenda for contemporary country songcraft. His is the standard by which success is measured in country music on every level, even self-destruction.”

It’s easy to dismiss Hank as a reckless drunk, but the booze and pills came not solely from his demons but also from his birth. Because Hiram Williams was born, in a small Alabama town, with spina bifida, an excruciating rupture of the spinal cord. So it was less his cheatin’ heart than his achin’ back that sent him down that “lost highway.”

Given his first guitar at eight, Hank absorbed the music and tragedy all around him. His mother, Lillie, played the organ in church, with her son by her side. His hard-drinking father, diagnosed with a brain aneurysm, was hospitalized from 1930 on. Hank was sent to live with an aunt and uncle. Reunited with his mother, their house burned down. The Depression descended.

“To sing like a hillbilly,” he later said, “you had to have lived like a hillbilly. You had to have smelt a lot of mule manure.”

Learning chords from a local bluesman, Hank began playing on the streets of Montgomery, Alabama. At 14, he formed the Drifting Cowboys, then dropped out of school and began roaming Alabama playing in honky tonks and clubs. His mother was his manager.

After his cowboys drifted into World War II, Hank re-formed the group in 1946. He failed an audition at the Grand Ol’ Opry but his wife talked a Nashville producer into listening to him. Signed to a contract, he began recording old Tin Pan Alley songs that he made his own.

“Honky Tonkin’.” “Lovesick Blues.” Then in 1947, he recorded his own composition with a rockabilly beat that presaged Elvis — “Move it On Over.”

I come in last night about half past ten

That baby of mine wouldn't let me in

So move it on over, rock it on over

Move over little dog cause the fat dog is movin' in.

Asked to explain the song’s appeal, Hank said, “There ain’t a man livin’ who hasn’t talked to his dog.”

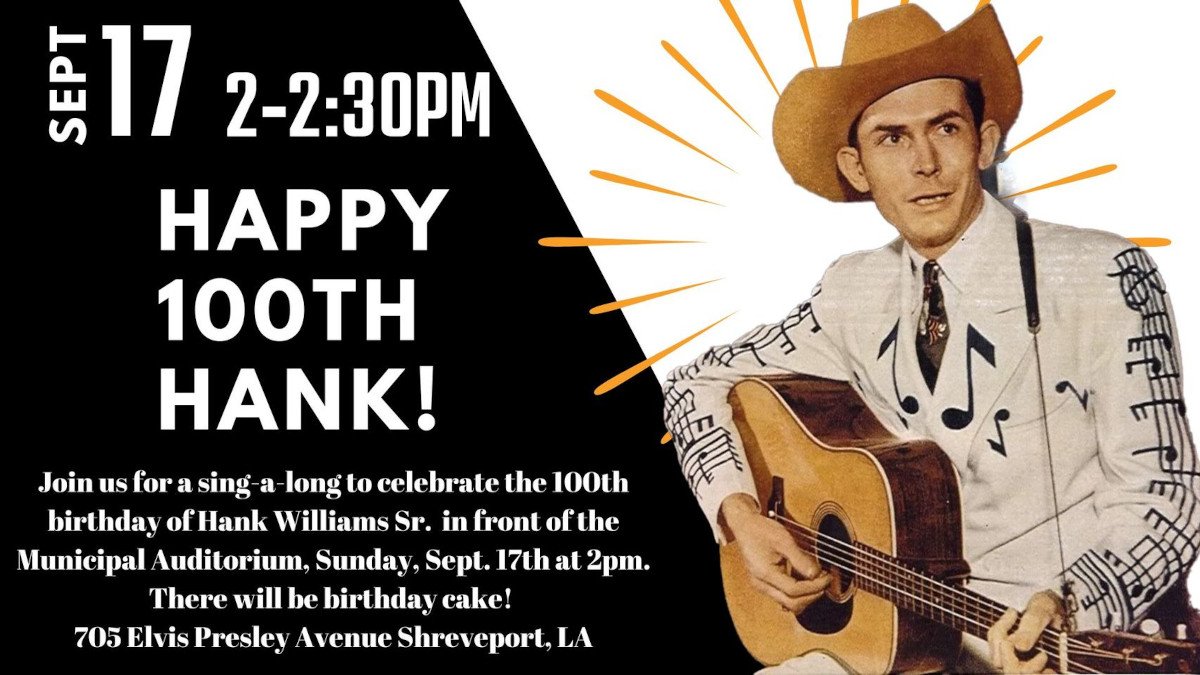

Yodeling and twanging live on KWKH’s “Louisiana Hayride,” Hank’s voice spread across the bayou and into Texas. And the five years began.

In 1949, the Opry gave him a second chance. He got six encores. Tall, skinny, topped by a cowboy hat, Hank Williams was country music. But unlike other Opry stars, he crossed over.

He sang on TV with Perry Como, toured with Bob Hope, sang with Kate Smith. Hit after hit followed, always through a drunken haze. Opry star Roy Acuff warned Williams about booze. “You got a million-dollar voice, son, but a ten-cent brain." Williams could not quit. Foolin’ around aggravated his back pain until he got a spinal fusion. The pain did not quit either.

In the summer of 1952, after he missed gigs because of drinking, the Opry fired Hank. He soon met an Oklahoma ex-con and quack who prescribed amphetamines and morphine. Already suffering chest pains, Hank gobbled them down.

That fall, driving to Louisiana with his new fiancée, Hank told her about his ex-. She had “a cheatin’ heart,” he said. As he drove, he dictated lyrics and crooned a melody.

Your cheatin' heart will make you weep

You'll cry and cry and try to sleep

But sleep won't come the whole night through

Your cheatin' heart will tell on you.

The last months were a nightmare of pain and liquor and pills. Best skip to the encores.

Country music could scarcely believe the news. At twenty-nine? Posthumous hits poured forth and the legend began. There was much to forgive and forget.

“To hear the tributes,” Hank Williams, Jr. said, “one would think that the entire city [Nashville] took turns kissing Daddy while he was still alive. While he was alive, he was despised and envied; after he died, he was some kind of saint.”

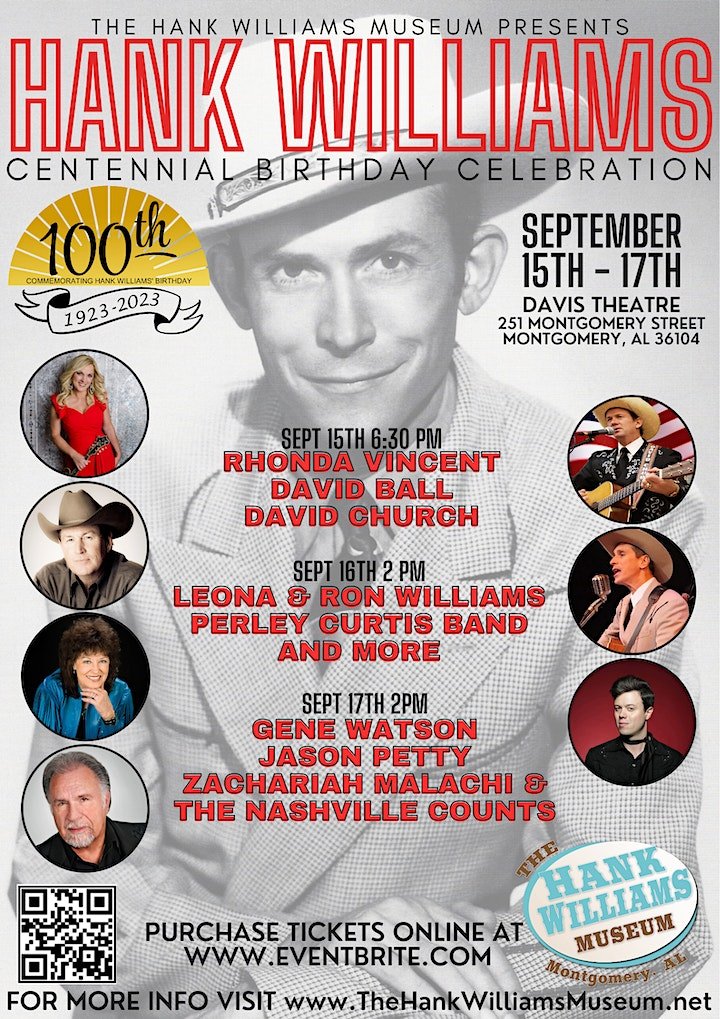

Hank is now in every music hall of fame, every top 100 song list, every heart that bleeds country. In 2010, he even earned a Pulitzer for “craftsmanship as a songwriter who expressed universal feelings with poignant simplicity.”

Ken Burns’ “Country Music” called him the “Hillbilly Shakespeare,” but Hank just called himself “good enough to play and sing.” As for fame, “I've been in the business long enough to know that fame is fickle, but the love for a good song lasts forever.”