TRUTH'S OWN HISTORIAN -- JILL LEPORE

CAMBRIDGE, MA — APRIL 2020 — As the world locks down, a door opens. Click! Footsteps on a stair. And eerie, Twilight Zone music. A female voice echoes. “There’s a place in the world where the known things go. . .”

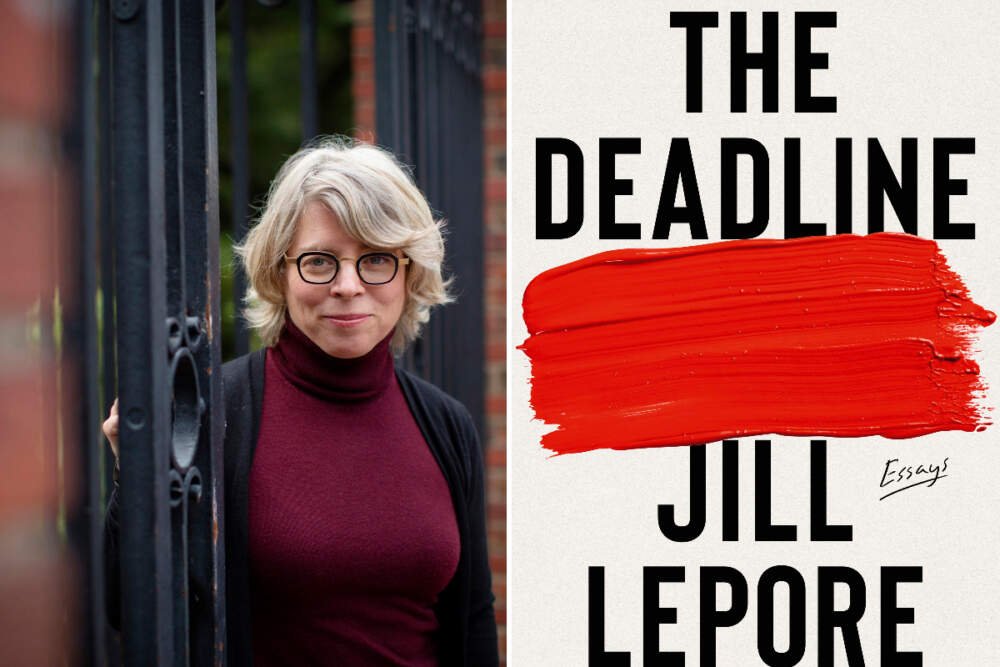

Podcasts are the soundtrack of our time. Chattering hosts and somber pundits struggle to focus our scattershot minds on minutiae. But when Jill Lepore added a podcast to her busy life, as Harvard professor and New Yorker staffer, she did not traffic in the trivial. She went straight for the question haunting our era.

Lepore had spent a lifetime preparing. During a bookish childhood near Worcester, MA, she “just always wanted to be a writer.” College steered her from a math major to English. Two years as a secretary at Harvard Business School taught her the politics of the workplace, and sent her on to grad school in American Studies at Yale.

There she fell in love — with a computer scientist whom she married, but also with the dusty, cluttered archives where history is forged. “The work of the historian is not the work of the critic or of the moralist,” she writes. “It is the work of the sleuth and the storyteller, the philosopher and the scientist, the keeper of tales, the sayer of sooth, the teller of truth.”

She was a quick study and an instant star. Her thesis on King Philip’s War, the first to present the Native-American perspective, won history’s prestigious Bancroft Prize.

Invited to Harvard in 2003, and soon to the New Yorker, Lepore stood out among historians for two reasons. She avoided “personal experience” histories — about childhood, motherhood, me, me, me. . . And she dodged the demand to “publish or perish” in journals written of, by, and for historians. A rare journal article critiqued historians.

“I have tried to write history differently.” Differently as in a) engaging; b) surprising; and c) relevant. Joining the New Yorker staff in 2007, Lepore suddenly had two full-time jobs, plus a third — raising three sons.

“I have a lot of energy,” she understates, but colleagues compare her to the subject of her bestselling The Secret History of Wonder Woman.

This Wonder Woman’s work has since included another dozen books, scores of New Yorker articles, teaching at Harvard, and three sons now in college. In 2018, she found time to write These Truths, the first full-length history of America written by a woman. In an age of bias and blowhards, the book’s even-handedness stood out from the Introduction.

“Some American history books fail to criticize the United States; others do nothing but. This book is neither kind. The truths on which the nation was founded are not mysteries, articles of faith, never to be questioned, as if the founding were an act of God, but neither are they lies, all facts fictions, as if nothing can be known, in a world without truth. Between reverence and worship, on the one side, and irreverence and contempt, on the other, lies an uneasy path.”

Truth. That slippery word again. Lepore’s faith in it made it the obvious topic of her podcast. So “Who Killed Truth?”

“The Last Archive” went beyond the usual suspects — social media and a mendacious president — to explain “how we know what we know and how come, lately, it seems we don’t know anything.” Ten episodes revealed truth’s many enemies. Lepore uncovered a forgotten murder case with flimsy evidence, the development of the lie detector, and the first computers to predict election results. Engaging, surprising, relevant.

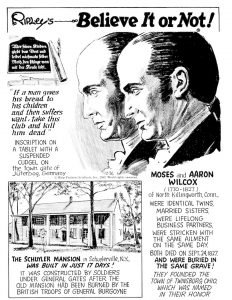

But the podcast’s second season added another adjective often applied to Lepore. Brilliant. Here she found a different archive, “the place in our world where the doubtful things go.” She then took listeners through the long and wacked-out history of alt-facts. Episodes studied the Scopes Monkey Trial, Ripley’s Believe it or Not, the rise of UFOs and reincarnation, Soviet propaganda, early anti-vaxx efforts, and how the Apollo 11 moon landing spawned ludicrous conspiracy theories.

The season ended with “Epiphany,” tracing how alt-facts came from the fringes into the thick of politics, culminating in January 6. It was fascinating, disturbing, and just the kind of sleuthing our “post-truth” society needed.

Today, having won almost every award, given every prestigious lecture, Lepore still feels most at home in archives. “Her gravitation towards dust, towards opening boxes that haven’t seen light for decades, has clearly never faded,” a New Yorker editor said.

Lepore’s latest book, The Deadline, collects 45 of her New Yorker articles under one cover. Of The Deadline, Andrew Solomon wrote, “If more of us could learn to think as she does, we could heal the riffs that threaten the social fabric of our democracy.”

Truth remains embattled, so damaged that some insist on a capital T, others in putting the word in quotes. Lepore disagrees. There is a Truth, historical truth based on evidence, not rumors, proof, not suspicion.

The truth about our past is rarely simple, often painful, and cannot be hidden forever. Sometimes it just takes a Wonder Woman to uncover it. And citizens to defend it.

“A nation founded on universal ideas will never top fighting over the meaning of its past and the direction of its future,” Lepore writes in This America. “That doesn’t mean the past or future is meaningless, or directionless, or that anyone can afford to sit out the fight. The nation, as ever, is the fight.”