STORY CATCHER OF THE PLAINS

Running Water Precinct, Sheridan County, Nebraska — 1928 — The old man was dying and his daughter came across the Plains to be at his bedside. All her life she had feared him. Cruel and bitter, he had fought her dream at every turn. “You know,” he wrote her, “I consider writers and artists the maggots of society.” But now the dying man had a final wish — “write my story.”

The border towns of Rock and Cherry counties were shaking off the dullness of winter. Galloping hoofs, the boom of the forty-four, and the measured beat of the spike maul awakened the narrow single streets running between the tents and shacks. . . And out of the East came a lone man in an open wagon, driving hard. . .

The sprawling emptiness of Nebraska has swallowed many a soul. Though Willa Cather made her home state heroic, even romantic, others have rendered it a launch pad for escape. But one Nebraska novelist dared to defy Western lore, to reject hero worship, and to write novels that “evoke one region of America as powerfully as William Faulkner’s portray another.”

Mari Sandoz barely survived a brutal childhood. Her father was a harsh man. Having fled his wealthy family in Zurich, Jules Sandoz crossed the Atlantic in the 1880s and kept moving, farther west, farther still to where, as his daughter wrote, “a man could build a home, hunt and trap in peace, live as he liked.”

Against a bleak, lonely landscape, scorching in summer, sub-zero in winter, Jules Sandoz carved out a bitter life. Irascible and demanding, he burned through four wives and worked six children to the bone. “A pioneer child always works hard,” his eldest daughter wrote. She called herself Marie but he called her Mari — MAH-ree. It took her years to embrace the name.

“Sometimes it seems that a quirk of fate has tied me to this father I feared so much, even into my maturity.”

Washing, cleaning, tending to younger siblings, young Mari somehow found time to “retreat into fantasy.” In idle moments, she stood at the farm’s gatepost where “people went by, the world went by, cowboys, Indians, and the wind and the birds. . .” She spoke only German until age nine, struggled in school, and finally finished eighth grade. She was 17.

Without telling her father, Sandoz rode miles to the nearest town to take a teacher’s exam. She soon found herself in a bad marriage and a raucous classroom. She soon left both to become a writer.

Though living in Lincoln, Nebraska, she called the 1920s her “Greenwich Village Time.” “Every time I’d get fifty dollars in the bank, I’d quit any job I had and write awhile. I was always under the impression that while I used up that fifty dollars, I would certainly sell a short story, but. . .”

A thousand rejection slips, long lonely hours, her father’s scorn — nothing would stop her. Then in 1928, Jules Sandoz asked his daughter to “write my story.” On through the Depression and the Dust Bowl, she plowed through his letters and summoned old stories from “the silent hours of listening behind the stove or in the wood box, when it was assumed that, of course, I was asleep in bed.”

Old Jules was rejected by every major American publisher. Done with dreams, Sandoz threw her stories in a washtub and burned them. But she kept Old Jules, revising it, submitting it. Finally, Atlantic Monthly published an excerpt. And in 1935, Old Jules became a Book-of-the-Month club selection.

Here was Plains life without nostalgia or apology. Here, one critic wrote, was “an amazing portrait. . . given to us as if she had cut it, like a sod, from the live ground.”

Old Jules paints “the unalterable sameness of the hills that spread in rolling swells westward to the hard-land country. . .” This harsh landscape is filled with harsh people — “the old buffalo-hunting Indians, the old traders, trappers, and general frontiersmen who looked with contempt upon the coming of the barbed wire and the walking plow.”

At the center is Jules, mean and unforgiving. “In Jules, as in every man, there lurks something ready to destroy the finest in him as the frosts of the earth destroy her flowers.”

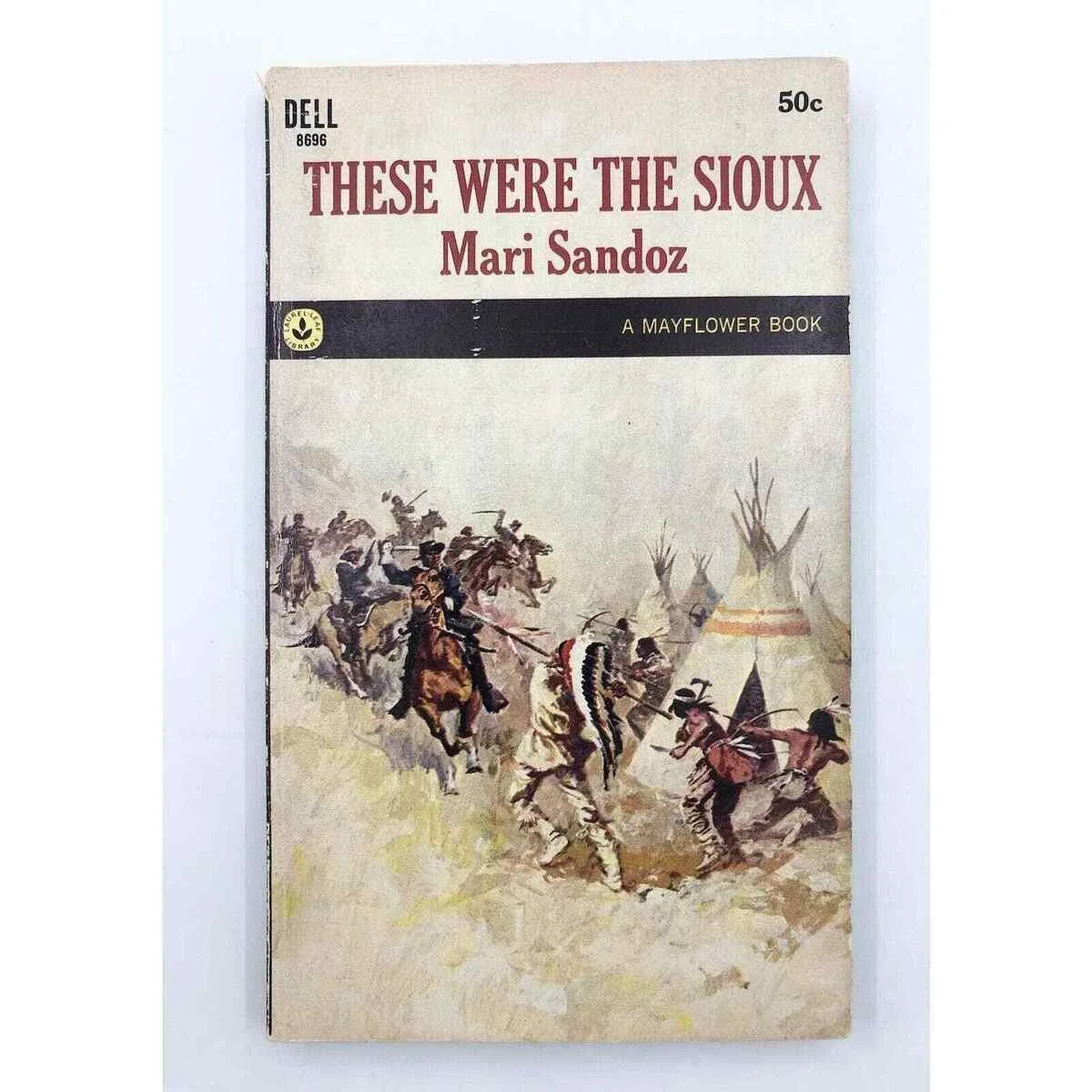

Sandoz wrote six more novels, but she is best remembered for her histories. Long before America regarded “Indians” with anything but romance or contempt, Sandoz roamed the Plains gathering their stories. In 1942, she published Crazy Horse.

Today, when natives write their own stories, most scorn such “Anglo” histories. But Sandoz silenced the skeptics.

“As a callow and ignorant youth,” Vine DeLoria Jr., wrote, “I was a little offended that a non-Sioux had written a biography of one of the legendary personalities of my tribe. Surely, I thought, she could know little of the nuances of meaning that characterize Indian communities.” But re-reading Crazy Horse, DeLoria “began to see that Mari Sandoz had presented a masterful and wholly authentic account in which almost every line rang true. I doubt if anyone else could tell the life of Crazy Horse as well as Sandoz does.”

Sandoz wrote several histories of Plains life. Cheyenne Autumn, The Horse Catcher, The Buffalo Hunters. . . She continued writing until a month before her death, in 1966.

The girl who fled into fantasy had become “the story catcher of the Plains.” “Mari Sandoz literally willed herself to become one of Nebraska’s greatest writers,” one historian noted. So although success had led her to New York, there was no doubt where she would rest.

On a cold and snowy March day, Sandoz’s siblings carried her casket up a hill overlooking the family ranch. Sandoz had asked to be buried atop the hill, but the day was bleak, the land ever unforgiving. “Put her down here,” one sister finally said. “That’s the best we can do.”