HEMINGWAY'S MAGICAL MEMOIR

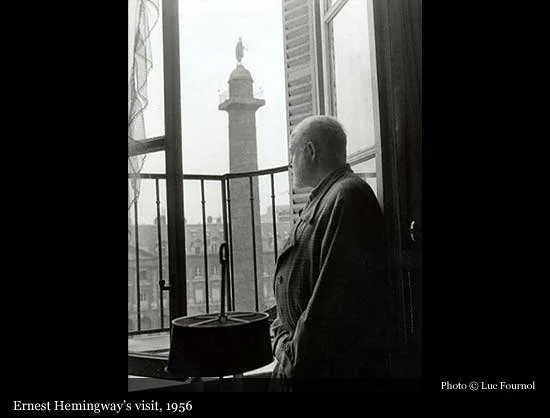

PARIS, NOVEMBER 1956 — Hemingway and a friend were dining at The Ritz. Bottles of wine, oysters no doubt, and views steeped in nostalgia.

Hemingway had not been to the Ritz since that August afternoon in 1944 when he commandeered a Jeep, drove it to the Place Vendome and stormed into the hotel shouting, “Where are the Germans? I’ve come to liberate the Ritz!” He was reminiscing about that day when Charles Ritz approached.

Did Monsieur Hemingway know that his trunk was still in the basement? It had been there since 1928 when he left for Key West. Hemingway remembered the lush Louis Vuitton trunk but did not recall storing it. He hurried to Ritz’s office where the trunk was soon set down. And opened.

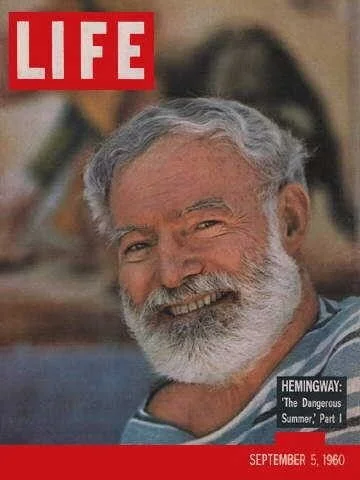

By 1956, Hemingway was America’s most famous writer. Four years earlier, he had bounced back from horrible reviews to write The Old Man and the Sea, then won the Nobel in Literature. The press followed his every move. Countless young men, honing words into bullets, dreamt of being “the next Hemingway.”

Yet fame hid darker secrets. Alcohol, a bruising life, and two plane crashes in Africa left Hemingway on the verge of breakdown. Electro-shock treatments cured his depression but addled his brain. He was not sure he would ever write again. Then he opened the old trunk.

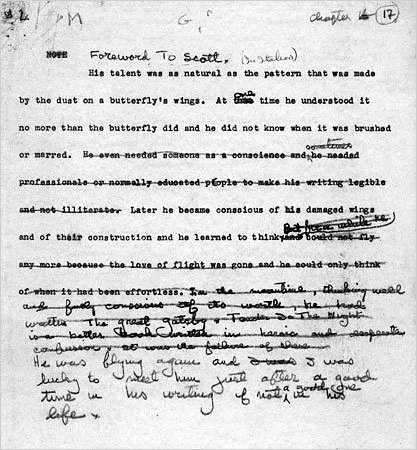

Along with newspaper clippings, receipts, and menus, the trunk contained stacks of notebooks. “The notebooks!” Hemingway shouted. “So that’s where they were! Enfin!”

He disdained memoirs. “It is only when you no longer believe in your own exploits that you can write your own memoirs.” But he was in his late Fifties, filled with that age’s longings and regrets. That winter, with the breezes of Cuba blowing the palms outside his home, he sat again at his typewriter. “Write one true sentence,” he had advised about beginnings. And as he typed, two-finger style, he was in Paris again. . .

Then there was the bad weather. It would come in one day when the fall was over. We would have to shut the windows in the night against the rain and the cold wind would strip the leaves from the trees in the Place Contrescarpe. . .

Every serious reader has an opinion on Hemingway. Macho jerk. Dazzling stylist. Sad old drunk. Critics, Edmund Wilson wrote, contrasted “the early master and the old impostor.” But as he wrote his way back to Paris, Hemingway revealed a softer self few had seen.

But Paris was a very old city and we were young and nothing was simple there, not even poverty, nor sudden money, nor the moonlight, nor right and wrong nor the breathing of someone who lay beside you in the moonlight. . .

He wrote all that winter, then took the work to his Idaho home. And the writing held his demons at bay. Because here was Paris, his youth, his discovery of life and literature and a new way of writing — lean and spare, lovely and brutal.

To have come on all this new world of writing, with time to read in a city like Paris where there was a way of living well and working, no matter how poor you were, was like having a great treasure given to you. . .

Hemingway had tapped the treasure in 1921 when, just married to his beloved Hadley, he took her to Paris where’d been sent as correspondent for the Toronto Star. Paris was in love with itself, as always, but a generation of American exiles — “the lost generation” — was in love with Paris. That generation would crack up, as Fitzgerald lamented. Hemingway would leave Hadley. Depression and war, madness and modernity would come. But for two years at his typewriter, Hemingway recovered the magic.

The memoir is not kind to his friends. Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, and others are revealed at their worst. But along with the author, the book’s protagonist is Paris, and from the Left Bank to Monmartre, the city shimmers as in an Impressionist masterpiece.

If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.

Early in 1960, he finished the book, took a final trip to Paris, then returned and descended into despair. One July morning in 1961, he loaded a shotgun. His wife, Mary, heard the blast. After mourning, then burying him, she went to work on the manuscripts he’d left. Two were novels, since published, mostly panned, but one was A Moveable Feast.

Published in May 1964, the book was a bestseller for the rest of the year. “Many of the sketches,” one critic wrote, “have the hard brilliance of his best fiction.” Edmund WIlson agreed. “That Hemingway could have resolved to risk such a candor of private regret and longing against the grain of his so carefully cultivated reputation, less than a year before his death, is the proof of the strength he could muster.”

A Moveable Feast has since joined its place among Hemingway’s best. Paris in the Twenties is now the stuff of fable. And sometimes fable can heal.

In 2016, when Paris was reeling from terrorist attacks, Paris est une fête became a best-seller throughout France. Guided by Hemingway, Paris fell in love with itself again, and with the American exile, lost in time and place, to whom the city meant so much.

There is never any ending to Paris and the memory of each person who has lived in it differs from that of any other. We always returned to it no matter who we were or how it was changed or with what difficulties, or ease, it could be reached. Paris was always worth it and you received return for whatever you brought to it. But this is how Paris was in the early days when we were very poor and very happy.

SHARE THIS STORY