THE REPORTER AND THE "GHOSTS OF MISSISSIPPI"

JACKSON, MS, JANUARY 10, 1989 — A specter is haunting Mississippi. Dozens of specters, actually. And on a brisk Friday evening, in a crowded movie theater, three specters come out of the shadows.

The FBI had a code name for its investigation of the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner — “Mississippi Burning.” Now, a quarter century after the killings, the name is a movie. In the audience, a young court reporter sits, legal pad in hand.

Shortly after the opening scene, a voice “deep and resonant,” speaks up. “‘That’s not accurate,’ he said. He leaned over and explained that it was Chaney, not Schwerner, who was the driver that night.” Though only assigned to review “Mississippi Burning,” by the time the credits roll, Jerry Mitchell is a changed man.

Fresh out of journalism school, Mitchell started at the Jackson Clarion-Ledger on the day after his 27th birthday. “Young, enthusiastic, and clueless,” he had covered the courts. But the drama of “Mississippi Burning” and conversations with the old FBI man who sat beside him that night steered Mitchell from current cases to “cold cases.”

These days, some call journalists “the enemy of the people.” Others distrust everything in the MSM (mainstream media). Lies, fake news, corporate propaganda — you know the slurs. But when a dogged reporter begins to dig, journalism fulfills another goal — “to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” And no reporter in our time has dug deeper than Jerry Mitchell.

“Jerry is a one-man justice machine,” said the Southern Poverty Law Center. “He has done what armies of prosecutors over the years either couldn’t or refused to do. He comes across as a regular, good-natured guy, but boy, is he dogged.”

Raised in Texas by Goldwater Republicans who “taught me right about race,” Mitchell was shocked to learn that the men who killed Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney were still at large.

“Martin Luther King Jr. had talked about the arc of the moral universe bending toward justice,” Mitchell wrote in Race Against Time. “But I wondered what he would say after a quarter century. Was there still time for the arc to swing around? I decided to find out.”

Mississippi, native son Willie Morris wrote, “hit the bottom of the barrel with these three murders in 1964.” By 1989, the Magnolia State had come a long way, with more elected black officials than any other state. But as Mitchell soon learned, the “ghosts of Mississippi” terrified everyone.

To re-open the “cold case,” Mitchell needed his editors’s support. Back in 1964, the Clarion-Ledger had led a chorus of denial calling the initial disappearance “a hoax.” But on the 25th anniversary, the Clarion-Ledger editorialized: “Reopening the Philadelphia (MS) murder case is simply the right and moral thing to do. It’s called justice.”

Justice demanded evidence. Told of a 1967 federal trial that charged 19 Klansmen with “civil rights violations,” Mitchell called the courthouse in Meridian. “The trial exhibits were all gone. Even the burned-out station wagon the trio had been driving had been destroyed.“ Was there a trial transcript?

The only transcript was missing. Mitchell soon found another copy, made to defend the studio behind “Mississippi Burning” in a libel suit. As he paged through the testimony, the shocking story came back to life.

The “hit order” on Schwerner. The lynch mob gathering that night. The arrest on a dark road, even the racist blather of the murderers. All could be used in a new trial, Mitchell learned. He also dug up files from the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, a state-run spy agency that had given Schwerner’s license plate to the Klan.

But when, above the byline Jerry Mitchell, the Clarion-Ledger headline read: “State Spied on Schwerner Three Months Before Death,” the ghosts came calling. Mississippi’s Attorney General shut down the official investigation. So Mitchell turned to another ghost named Medgar Evers.

Byron De La Beckwith, who later boasted of gunning down Evers in his driveway, had twice been acquitted. Mitchell uncovered more evidence, again linking the state spy agency to the case. A committed prosecutor went to work and in 1994, Beckwith was convicted of first-degree murder. Jerry Mitchell kept digging.

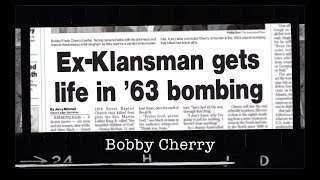

Alabama had convicted two men of the 1963 Birmingham church bombing that killed four little girls. But a third suspect had an alibi. Bobby Cherry swore he had been home watching wrestling on TV when the bomb was planted. Then Mitchell got the TV Guide from that night. There was no wrestling on TV. Cherry was convicted in 2002.

And Mississippi Burning? In 2002, a Jackson high school teacher contacted Mitchell. When three of his students began investigating the state’s most notorious case, the teacher somehown convinced Edgar Ray Killen, long thought to be the mastermind of the murders, to do an interview. Working with Mitchell, the students dug up more evidence, and in 2005, Killen was convicted. In the courtroom to hear the “guilty” verdict were Rita Schwerner, brother Ben Chaney, and Andrew Goodman’s mother. All wept.

“I feel like you have brought Andy back into this house,” Carolyn Goodman told the students.

Jerry Mitchell’s work has inspired more investigations throughout the South. Since 1989, 29 “cold cases” from the Civil Rights Era have been re-opened, resulting in 27 arrests and 22 convictions.

Mitchell worked for the Clarion-Legder until 2018, then founded the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting. Widely acknowledged as “a true hero of contemporary American journalism,“ he has won countless awards, including a MacArthur Genius grant. He shrugs it off with a tribute to journalism itself, penned for his current employer, Mississippi Today.

“Despite criticism, we believe that journalism remains one of the world’s most noble professions. Despite cursing, we believe that this world needs more good journalism, not less. Despite attacks, we believe that journalism continues to make a difference in people’s lives.”