WHEN DEMOCRACY SPOKE. . . AND LISTENED

AMERICA’S LIVING ROOMS — MAY 30, 1935 — Dust coats the streets and marble monuments of Washington, DC, dust blown all the way from the Midwest. Nearly 100,000 Americans proudly call themselves communists or fascists. Unemployment tops 20 percent. Democracy is on the ropes.

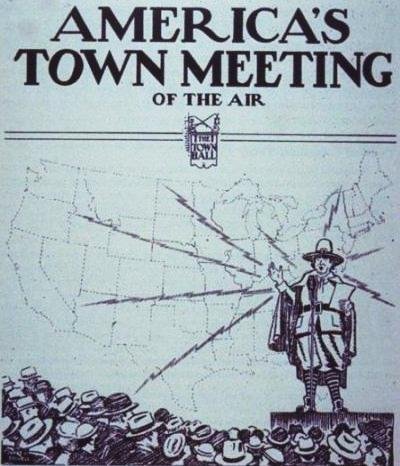

Static,. . . t urn the dial, more static. The scratchy strains of an orchestra. Kate Smith belting out a song. And then . . . A clanging bell and the call of a town crier. “Oyez, oyez, Town Meeting tonight! Bring your questions to the old town hall! Tonight: ‘Which Way America — Communism, Fascism, Socialism, or Democracy?’”

A band breaks into “The Stars and Stripes Forever,” then fades into the call of “Good evening, neighbors! Welcome to ‘America’s Town Meeting of the Air.’”

Democracy, wrote E.B. White, “is an idea which hasn’t been disproved yet, a song the words of which have not gone bad.” The core of the idea, the chorus of the song, is conversation. And at democracy’s lowpoint, radio brought that conversation into American homes.

George Denny was a part-time actor and full-time small ‘d’ democrat. Alarmed one day when his Scarsdale neighbor refused to listen to FDR’s “Fireside Chat” “because he disagreed with him,” Denny had an idea. Radio had other panel shows — “American Forum of the Air,” “People’s Platform,” and “The University of Chicago Roundtable.” But all were dull and dry, lectures not conversations.

Why not a town meeting, where panelists spoke but then turned democracy over to the audience? Why not “unrehearsed, spontaneous discussion?”

NBC agreed to a six-week trial. Little was expected of the show, but with the country flat on its back, Americans were eager to talk, even listen. On its debut show, an audience of nearly 2,000 filled Town Hall in Mid-town Manhattan. To Denny’s delight, they cheered, booed, and hissed. The following week, Denny received 1,000 letters from all over America. Town Meeting was in session.

By 1937, “Town Meeting of the Air” was on 225 stations coast-to-coast. More than a thousand “listener clubs” met to listen together, then argue on into the night. Transcripts of each show, available for a dime, were published, sold to the public, and sent to civics teachers. America was talking, listening, asking.

Listen! Each “town meeting” now sounds like a rusty timepiece — the pompous opening, the stilted announcer, speakers going on for 10-15 minutes. But the topics are straight out of today, still unresolved, still worth talking about IF we could talk to each other.

— “Do We Have a Free Press?”

— “Are Parents or Society Responsible for Juvenile Crime?”

— “Is America Losing its Morals?”

Panelists included journalists and politicians, authors and actors. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins explained the new Social Security. Langston Hughes spoke on “Let’s Face the Race Question.” Novelists Pearl Buck, H.G. Wells, and Richard Wright weighed in. But the real stars of democracy were the people themselves.

The last half-hour featured short questions from the audience. No insults were allowed, no personal attacks, but audience members freely challenged ideas. “The speakers heckle each other and the audience heckles everybody,” TIME wrote.

Despite what one critic denounced as “a scattered but recurrent percentage of irresponsibles, drunks, and crackpots,” Denny welcomed all voices, especially those with “fire and color.” As he took the show on the road, spending six months a year hosting from venues throughout America, all that mattered to him, to the audience, was keeping the conversation going.

Denny often held a ball up before the audience, half black, half white, with one side concealed. He’d ask what color the ball was. People shouted the obvious answer. Then Denny turned the ball over. Seems there were two sides. . .

“‘Town Meeting,’ one critic noted, “made it essential for a man to listen to all sides of an argument in order to hear his own.” And on radio, the town meeting, an old New England institution, “lengthened its shadow until it stretched to the Pacific Coast.”

During World War II, Denny found it harder to control an edgier audience. After the war, politics gave way to existential debate. “Are You Worried about the Atomic Bomb?” “Does Modern Art Make Sense?”

When TV began babbling, the network tried simulcasts, but “Town Meeting” made bad television. The show struggled, Denny left, and “Town Meeting of the Air” was finally canceled in 1956, 21 years after its six-week trial.

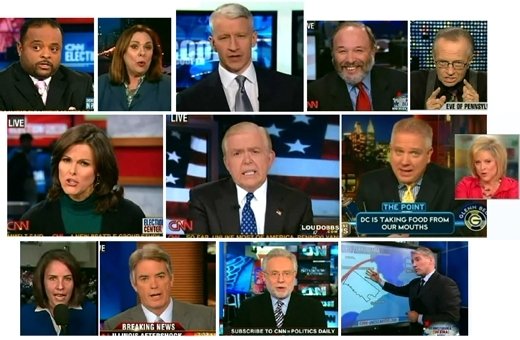

Today, in our cabled, online, social media spewing world, there is plenty of opinion and no shortage of shouting. But listening? Why no “Town Meeting of the Internet?”

Back in 1935, NBC and other networks were under FCC orders to provide substantial “public service” shows to fill the “public’s airwaves.” In 1949, the FCC added a “Fairness Doctrine” requiring stations to provide programs “not for the private interest, whims or caprices [of licensees], but in a manner which will serve the community generally.”

But by the 1960s, public service shows, once on prime-time, were crammed into Sunday mornings. And in 1987, arguing that the proliferation of cable allowed for plenty of viewpoints, Ronald Reagan vetoed the Fairness Doctrine. The conversation became a cacophony. And democracy?

Listen! The bell is ringing again. But is it the bell of the town crier calling citizens to a fresh and frank conversation? Or, barely heard beneath the shouting, is it the bell that tolls for democracy? Oyez, oyez.