DEMOCRACY -- THE NEXT GENERATION

SINCE THIS ARTICLE RAN IN NOVEMBER, EASTHAMPTON HIGH’S “WE THE PEOPLE” TEAM TOOK THEIR EIGHTH STRAIGHT MASSACHUSETTS STATE TITLE. THEY COMPETE FOR THE NATIONAL TITLE ON APRIL 8 IN WASHINGTON, DC.

NOV. 19, 2024 — EASTHAMPTON, MA — Slightly sleepy, sporting hoodies and jeans and “was’up’s” for their friends, nineteen juniors shuffle into Room 204 at Easthampton High. The time is 7:45 a.m but the classroom clock is covered by a sign reading “Time to Learn.”

And before the students can slouch or even settle, the future of democracy stands at the board to introduce today’s topic. “I want to start with points of confusion. What do you want me to clarify about the 14th amendment? And remember, this is your time to fail. You don’t need to know it all now.”

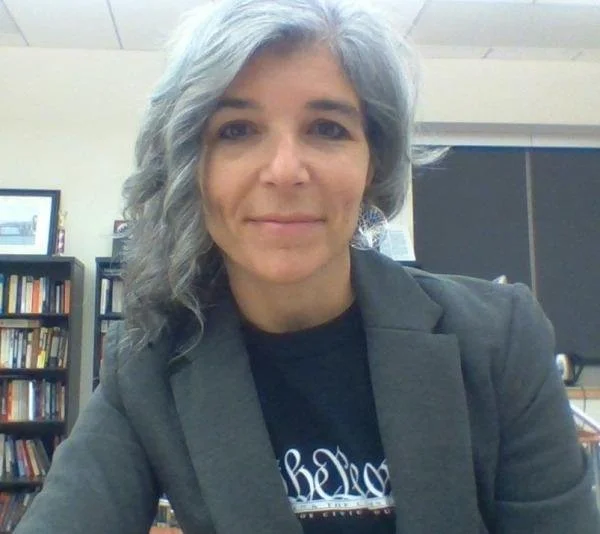

Kelley Brown is the teacher everyone should have for any topic, any time. Yes, she has the creds — D.A.R. National American History Teacher of the Year (2022), Massachusetts History Teacher of the Year (2010), etc. But beyond awards, just watching “Ms. Brown” own her classroom and share her enthusiasm is a lesson in hope.

“Okay, what is a fundamental right?” Sporting an American flag embroidered on her sweater, she strides among students, calling on a few, taking a phone from another, giving a handkerchief to one who sneezes.

“Something so fundamental that. . .”

“So fundamental,” a student says, “that it can’t be taken away.”

“Right.”

This will be on the test, the test of democracy. And Americans don’t exactly ace that test. Last year, when the U.S. Chamber of Commerce surveyed 2,000 adults, 70+ percent failed a basic civics quiz. Just half knew the branch of government where bills become laws. (Congress, duh.)

A third could not name all three branches of government. More than half thought the First Amendment means that Facebook must permit any and all speech. But Kelley Brown just told her students that the First’s “Congress shall make no law. . . restricting freedom of speech” says nothing about private companies.

So, America, where do we go from here? Back to class.

Ms. Brown is at the board again. Knowing that students are usually more talked at than listened to, she sets a clock. Fifteen minutes, that’s all she’ll take. Go! She draws an umbrella and labels it “The Due Process Clause.” Under it are shielded three kinds of rights protected by — you guessed it — the 14th amendment.

Around the classroom, there are a few dull stares. Hey, it’s 8 a.m. and these are teenagers. Many would rather be doing something other than discussing the State Action Doctrine of 1883. But Ms. Brown, finishing her fifteen minutes, lets them do the next best thing to sleeping — talking to each other.

Working in groups of four, students follow Brown’s request to “explain, explain, explain.” Some get help from student mentors, seniors who took this class last year, when Brown’s team again won the state civics competition (seventh win in a row) and made the finals of “We, the People.” The national competition tests understanding of American civics. Brown’s teams often place in the top 15 and were national champs in 2020. Last year they finished tenth among 50 schools.

In one corner, mentor Devin O’Brien is explaining the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling on abortion. “Do you know what trigger laws are?” O’Brien asks the group. When she explains, then refers to the 1960s Griswold case on birth control, a girl objects.

“Do you think just because women should have access to birth control, they should have access to abortion?”

The conversation continues.

At the back of the class, Samuel Barr tells me why he returns to Brown’s class as a Student Mentor. Barr plans to study engineering but “there’s something different about how this class is taught. It’s like we’re all a bunch of mini-coaches.” And while a passion for “how a bill becomes a law” can get you labeled “a nerd,” Barr admits, “when you finish tenth in the nation, you can back yourself up.”

As the class goes on, Ms. Brown is all over the room. She sits with one group, listening, then shares suggestions with another. By 9:15, I am exhausted just watching her, but she concludes with reminders of upcoming topics and next week’s oral exams.

“We, the People, The Citizen and The Constitution” is an elective, Brown tells me. But principal Bill Evans goes deeper, assuring me that Brown has made civics one of the most popular electives at Easthampton High. Most schools have a few such gifted teachers, but most schools do not have year-long classes in civics.

Just nine states and D.C. require a year of high school civics. Thirty-one states require just a semester, and ten states have no civics requirement at all. The upshot? While two-thirds of Americans remember studying civics in high school, only 25 percent are “very confident” they could explain how our government works. Kelley Brown aims to change that.

She considered becoming a lawyer, she tells me, but “I just absolutely love teaching.” Still. . . civics? I seem to remember my own class, and cries of “borr-rinng!” Brown disagrees. “I tell my students that once you come to know something, you come to love it.”

And this test? This test of democracy? Is America going to pass it? Brown is neither “optimistic nor pessimistic.” But her immersion in the Constitution and the pillars of democracy gives her confidence. “We have enduring institutions that from time to time get tested,” she admits. “But I have confidence in American democracy. The founding generation thought hard about how to check human nature, and those checks and balances, plus a virtuous citizenry create the most ideal situation for our system to endure.”

Time for another class. Heading back to Room 204, like a good lawyer or teacher, Kelley Brown saves her strongest argument for last. “These kids make me hopeful,” she says. “I really love them and I love what we do. I think we’ll figure it out. I put my hope in them.”