THE ARTIST AND THE REDNECK

CHATTANOOGA, TN, SUMMER 1950 — Two brothers, one tall, lean, and mean, the other short, squat, pasty-faced, board a crowded bus. It’s hot and they have to stand. The older brother — Tommy — holds onto a strap while the younger — Barry — clings to Tommy. Then Barry spots a seat at the back of the bus. He bolts from Tommy and sits between two black women, beneath the sign reading: “THIS PART OF THE CAR FOR THE COLORED RACE.”

In a deeply divided America, we seem to agree on only one truth — that we are deeply divided. Though our battles rarely end in fist-fights, as this one did, we remain in separate camps, silenced by scars of the last time we tried to reach out.

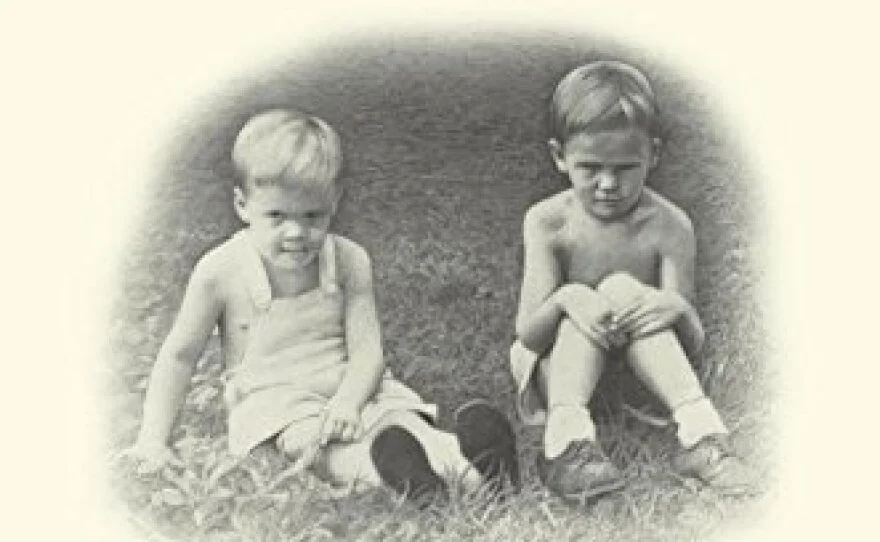

Growing up in the 1940s and 50s, Barry and Tommy Moser shared an idyllic childhood. Roy Rogers and the Lone Ranger. Kind parents, goin’ fishin’, playing Cowboys and Indians. But theirs was also a Southern childhood. Jim Crow segregation. White supremacy. The n-word flying freely. “I don’t think I heard the word ‘Negro’ pronounced properly until I was in high school,” Barry recalled.

“Without opportunity to be otherwise,” Moser writes in We Were Brothers, “Tommy and I were racists, born into the byzantine machinations of the Jim Crow South.”

The brothers took different paths. Tommy, blind in one eye and “hypersensitive to failures, humiliations, slights, and hurts,” dropped out of military school, worked odd jobs, then worked his way from bank clerk to branch manager. He stayed in the South and stayed a Southerner in the tradition of “good ol’ boys.”

But Barry had a different take on race. Both brothers grew up with a black friend, and both loved their mother’s best friend, Verneta, whose family lived just down the street. But Tommy had been out driving his red MG the night Verneta came over in tears, terrified by the Klan’s resurgence in Chattanooga. And while Barry was at college, “examining my family’s teachings about race. . . Tommy, on the other hand, stayed faithful in the racist tack that both of us had been harnessed with.”

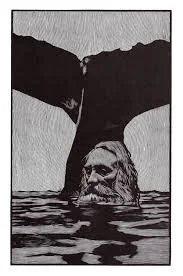

In 1967, Barry fled the South “to escape the racism all around me.” He moved to New England, settled down, raised a family and became, one critic said, “probably the most important book illustrator working in America today.” In illustrations of classics from Alice in Wonderland to the Bible, from Dante to Moby Dick, “the passion, craft and imagination of Moser’s work have an impact that leaves the viewer speechless.”

For thirty years, living “a thousand miles apart, both geographically and emotionally,” Barry and Tommy rarely spoke. When they did, Tommy’s bullying erupted in rage, resentment, and always, the n-word flying freely. More years of silence followed, years in which Barry watched “films in which brothers are close and go places together and have adventures,” and wept.

In December 1997, Barry was working on his masterpiece, his massive Pennyroyal Bible, when Tommy called to tell him about the death of a cousin. But lament gave way to another argument, more insults, the n-word again. Barry slammed down the phone, then fired off a letter calling Tommy “an embarrassment to me. . . You shouldn’t call me until you can act like something other than an ignorant fucking redneck.”

A week later, Barry received “the fat letter.” Seven pages, eloquent, impassioned, without a single n-word. Tommy apologized for his bullying but stuck by his guns — he owned many. “I don’t hate blacks but I do hate affirmative action, racial preference and equal opportunities,” he wrote. He went on to cite being bullied himself, by a neighbor and by cadets at military school. But did Barry know how proud Tommy was of him? “I have framed the articles that were in People Magazine and Newsweek and American Artist. I do love you.

Just, Tom.

PS — Don’t grade this letter.”

In reply, Barry gave Tommy “a solid A” for his writing, then concluded: “I would like, before one of us dies to have a conversation with you about ideas and ideals. About the things we hold dear. Sacred things.” The letters led to phone calls. Once or twice a month, one brother called the other. They did not discuss politics.

“We told jokes,” Barry recalled. “Lots of them. We swapped tales, both tall and real. We bitched and griped about getting old. . . We commiserated about the death of our dogs and about our own health and mortality — his cancer, my diabetes. Yet our conversations were never morbid or morose, and they rarely ended without laughter and each saying to the other, ‘I love you.’”

Barry and Tommy met again in October 2002, near Tommy’s home in Nashville. They went to dinner, then Sunday brunch. When they said goodbye, “Tommy and I embraced, and as we did I kissed him on the cheek and said, ‘I love you.’ He hugged me even tighter and said, ‘I love you, too, my brother.’” Barry suspected this would be the last time he saw his brother. It was.

Tommy died of cancer in 2005. Barry, thankful that “Tommy and I enjoyed eight years of brotherhood before he left, a brotherhood that was without anger, or recrimination,” poured out his story in his “achingly honest, and troubling memoir.” (Jackson Clarion-Ledger).

But the story of Barry and Tommy Moser goes beyond one troubled pair of brothers. In a deeply divided America, we seem to agree on only one truth. . . Yet despite our different lives, different beliefs, there remains a different path forward. There is so much more to us than our politics. There is family in all of us. Isn’t it about time for the letters and phone calls?

SHARE THIS STORY!