HEARTS IN GRANITE

CENTRAL ILLINOIS — 1915 — No one called it “flyover country,” but America was already bored with the Plains. Here, if anywhere, people led what Thoreau dismissed as “lives of quiet desperation.”

Little towns in the Land of Lincoln had their granges and their grocery stores, their small schools and small hopes. Up and down Main Street, faces seemed as flat as the land, lives as plain as American Gothic. Until Spoon River.

Where are Elmer, Herman, Bert, Tom and Charley,

The weak of will, the strong of arm, the clown, the boozer, the fighter?

All, all, are sleeping on the hill.

One passed in a fever.

One was burned in a mine

One was killed in a brawl. . .

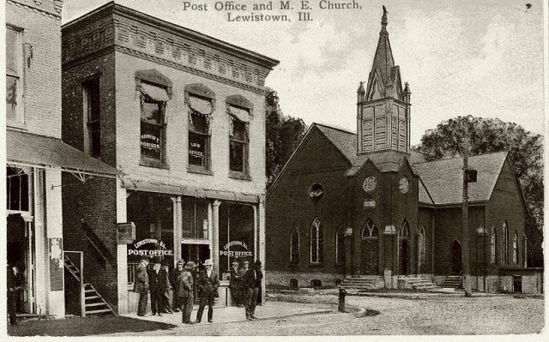

When Edgar Lee Masters was growing up, Lewistown, Illinois had 1,700 people. Lives were entwined, entangled, with secrets spread all over the block. People hid their passions behind closed doors. They carried failures, sins, and sorrows to the grave.

Then in 1906, Masters began roaming Lewistown’s Oak Hill Cemetery, gathering names. He changed a few, turning Henry Phipps into Henry Phelps, Margaret George into Julia Miller. . . Other names he crafted himself. Voltaire Johnson, Hamlet Micure. . . Then Masters let these “characters interlocked by fate” speak for themselves.

AMANDA BARKER

Henry got me with child

Knowing that I could not bring forth life

Without losing my own. . .

WENDELL P. BLOYD

They first charged me with disorderly conduct

There being no statute on blasphemy. . .

Masters, a middle-aged lawyer, had moved to Chicago where he briefly worked with Clarence Darrow. But each evening, he wrote poetry. Published in journals, most of it was ignored. Then an editor gave him an anthology of Greek epigrams. Why not let the dead speak for themselves, Masters thought.

What began as a novel turned into epitaphs. Masters grew obsessed with the lives he was sketching. Often writing until dawn, he interwove a town’s hardscrabble stories into 244 epitaphs. In 1914, the poems were serialized in a small journal. The following year, Spoon River Anthology was published. America had never read anything like it.

“At last, America has discovered a poet.” — Ezra Pound.

“Once in a while a man comes along who writes a book that has his own heart-beats in it. The people whose faces look out from the pages of the book are the people of life itself." — Carl Sandburg

Translated into several languages, Spoon River Anthology became the best-selling poetry book in American history. Seems the lawyer/poet had touched a nerve. In 1915, America was still half rural, but burgeoning cities were filling with small town refugees. Tired of myths touting rural innocence, they welcomed the brutal honesty of Spoon River.

CHASE HENRY

In life, I was the town drunkard

When I died, the priest denied me burial. . .

NELLIE CLARK

I was only eight years old;

And before I grew up and knew what it meant

I had no word for it, except

That I was frightened and told my mother

And my Father got a pistol

And would have killed Charlie, who was a big boy. . .

With nothing left to fear, the dead tell their stories, naming names, settling grudges. Minerva Jones tells how Butch Weldy raped her. She died during an abortion. Doctor Meyers, the abortionist, tells how he died in jail, blaming Minerva. Pages later, Butch Weldy, never mentioning rape, tells how he “got religion and steadied down.”

You don’t read Spoon River Anthology. You fall into it. Each epitaph begins with a confession — LOUISE SMITH — Herbert broke our engagement of eight years/When Annabelle returned to the village. . . And suddenly you are inside the life of an immigrant, a murderer, a long-suffering wife. . .

YEE KEW

They got me into the Sunday-school

In Spoon River

And tried to get me to drop Confucius for Jesus. . .

“Few of the ingredients of human corruption and vulnerability are missing from the depositions of these underground witnesses,“ the poet May Swenson wrote. But along with disillusion, the dead of Spoon River find joy.

FIDDLER JONES

And I never stopped to plow in my life

That someone did not stop in the road

And take me away to a dance or a picnic

I ended up with forty acres;

I ended up with a broken fiddle —

And a broken laugh, and a thousand memories

And not a single regret.

America swooned over Spoon River but Lewistown seethed. The book was banned yet read all over Masters’ hometown. A local historian remembered, “Every family in Lewistown probably had a sheet of paper or a notebook hidden away with their copy of the Anthology, saying who was who in town”

Stunned by success, Masters quit law and moved to Manhattan. Holed up in the Chelsea Hotel, he wrote biographies, novels, and a dozen more poetry collections. None equaled Spoon River, not even its sequel. Yet in speaking for the dead, Masters had ennobled the living. Spoon River Anthology has been made into an opera, several song cycles, a folk tune sung by Steve Goodman, a radio play, a computer game. . .

Edgar Lee Masters died in 1950. He was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, beside the graves of the dead whose lives he had woven. His gravestone is etched with the words of Percival Sharp, thought to be Masters himself.

It is all very well, but for myself I know

I stirred certain vibrations in Spoon River

Which are my true epitaph, more lasting than stone.