MY RENDEZVOUS WITH SUN AND MOON

L.A. — SATURDAY, FEB. 24, 1979 — Broke, bored, bartending at a pizza joint, I did not ask the universe for much.

Six months after hitching from Scotland to Greece, here’s what I had to my name: a rusted out Datsun with 150,000 miles, a cheap guitar, and $600 -- half what I needed for my next trip -- anywhere.

That afternoon at a wedding reception, a friend told me about a total solar eclipse — Monday, 8:16 a.m. Goldendale, Washington, 1,000 miles north. The last American eclipse until 2017. Tuned out as I was, that was news to me, but I found a pay phone and called Shakey's. “Tell the boss,” I told some teen, “that I won't be in on Sunday night. Or ever again. Sorry for the short notice. I'm headed for the sun.”

We cleared L.A. by dusk and headed north into the night. With Mike’s gold VW humming and the radio blaring the Doobie Brothers' "What a Fool Believes," we churned over the Grapevine, then down into California's Central Valley where lights flickered across flat farms.

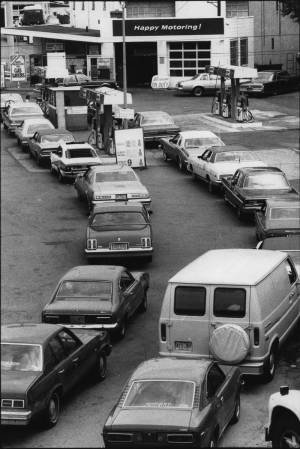

Stopping for gas in Kern Lake, we calculated. We would spend the night in Mike’s Berkeley apartment, get what sleep we could, then head out by nine. But if any trouble occurred, we might not make it. Corn Nuts and Cokes in hand, we got back in the car, me driving now, just beginning to understand why we, as much as sun and moon, needed this rendezvous.

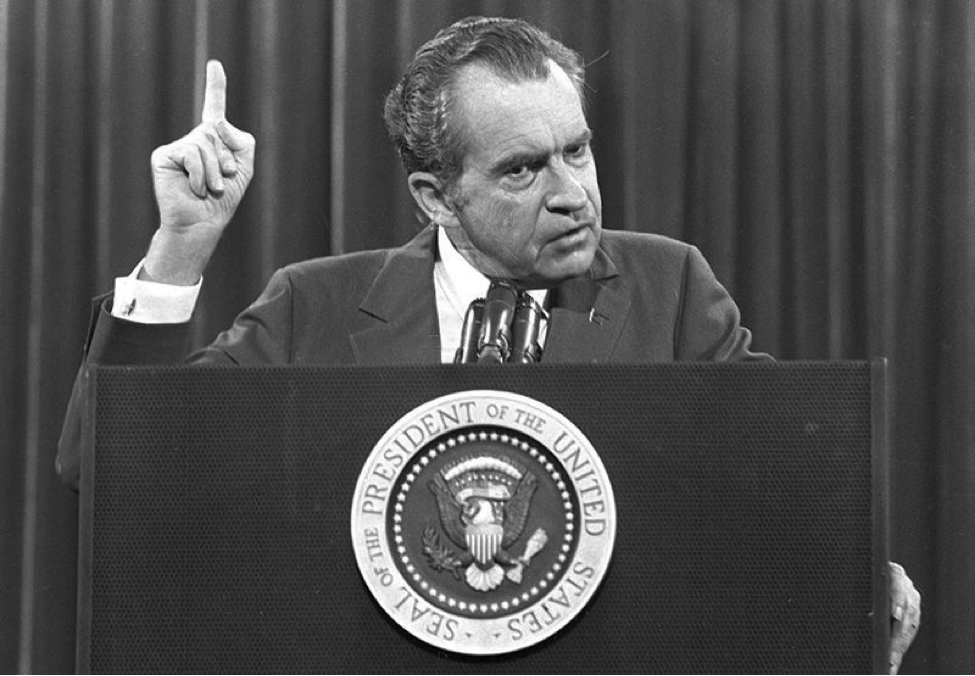

Our teen years had been Vietnam, our early twenties Watergate. Now we felt the "malaise" months before Jimmy Carter lamented it. America in 1979 was nothing like the triumphant nation whose history we were force-fed. Scarred by scandal and defeat, ours was a nation treading water, where we felt that something unnerving would happen soon, or worse, that nothing would.

These were the sunset days of our youth, but rather than paint the sky, the light was ebbing with neither a bang, nor a whimper, but with weddings. What a fool believes, the Doobies told us, the wise man has the power to reason away. Reason told us to stay at that wedding reception, drink, dance, meet a bridesmaid. But fools? The fools in us said to do something before life left us tight-lipped and tied down. Forty hours of driving for three minutes of miracle seemed just crazy enough to beat back the malaise.

We slept five hours in Berkeley, then hit the road again. Only as Mike’s Gold Bug swept through Northern California and into Oregon, did I realize not what I had left behind, but who.

The one person I should have taken to the eclipse was my mother. From the time I could stay up late, she had led me from the TV into the backyard. Winter: it was always a winter night, darker, colder, clearer. And there, rising over the stucco homes were the landmarks of her universe, the spangled void into which she would fall, lost to cancer, within five years.

Even now when I look at the stars, I am seven again, and there at the end of her pointing finger are the belt of Orion, the jeweled Pleiades, the occasional wandering planet. She knew them all as if they -- not some open road -- were her escape route. Already counting the years until Halley's Comet, which she would not live to witness, she would have given her soul to see a total eclipse. But I was 25 and clueless. I did not ask her along.

On up I-5, Medford, Roseburg, Eugene. . . Sun hidden in clouds, moon on the far side, each knowing the dance, knowing the appointed moment. 8:16 a.m. Crossing through Portland late Sunday night, it was clear we would make it. With just hours to spare.

We pulled into Goldendale at 4:00 a.m. A low-slung town, a few streetlights, and bar after bar, black. But on every hillside, in every parking lot, cars, trailers, and RVs were thick in anticipation. We had come far, but America had beaten us here. License plates read Michigan and Texas, Missouri and Tennessee. This was the last eclipse in America until some impossible year in an endangered future, and a weary nation had come to claim a piece of sun and moon.

We parked in a vacant lot. We had made it. Let the sun rise! Let the moon pirouette! Let the show begin! We got out, shivered, realized we were not in L.A. anymore. We hustled back in the car and tried to sleep, but by 7:00 a.m., as tinny transistor radios spread the news, we were up, ready to make the sky our looking glass.

When we first spotted the sun, it was moving in and out of lace. The lovely crescent was bright, perfect. It was happening. Saturday’s wedding, our frantic dash, our quest to make meaning out of being twenty-five— all meant nothing. It was happening and we were there to see it.

But would we see it? Clouds thickened, hiding the crescent. The temperature plummeted and a sigh spread from vacant lot to hillside. Heads lifted from telescopes. 8:10. 8:12. We sensed, we saw, we felt the clockwork. But there was no sun.

Then at 8:13, a break in the clouds! Lace drifted across a golden sliver, but even this blinded and burned. Across the hillsides, we were all Easter Island statues, heads lifted as one to the slim crescent, now slimmer, slimmest. Then came the shadow.

It swept across the landscape like a cloud in a time-lapse film. It did not bring full night but an early dusk, like the dreariness of a drenching rain. Most startling was the silence. Annie Dillard, watching from the Yakima Valley, later described the moment of totality: "From all the hills came screams." But the screams were internal, the shock of seeing the sun go black, punching a hole in the sky.

The corona did not flutter, nor did the sun seem to move. Only the clouds, like damask draped over a coal-black plate, were in motion. For another minute, time seemed fixed. No one stirred. Applause would have seemed tacky. Utter reverence was the only fitting tribute. Silence continued until, our three minutes up, a diamond bulged from the black plate. The diamond flared, then burst into a blazing curve that forced us to squint, hold up a hand, turn away.

As we drove south, I thought of my mother back home. She would be watching as ABC News covered the eclipse. Portland had missed it — clouds. But thousands had seen the miracle, in Idaho, across Montana and North Dakota. And in Goldendale, which we left even as the sun was still a crescent.

The next American eclipse, Frank Reynolds said, would be in 2017. August 21. Imagine. "That's 38 years from now. May the shadow of the moon fall on a world at peace."