THE SIGNS, THE RAVE -- BURMA SHAVE!

MINNEAPOLIS — 1925 — The Odells were upset. The family’s new shave cream was sitting on shelves. It was the 1920s! Roaring and romancing! Didn’t men need to shave?

Clinton Odell was about to give up on Burma-Vita, but instead he listened to his son, Alan. All right, the buttoned-down exec said. They would try an advertising gimmick. If it worked for a gas station, it might work for shave cream. Two hundred bucks ought to buy enough skinny boards. And the first signs went up.

Spread along Route 65 outside Lakeview, Minnesota, three signs, each 100 feet beyond the last, read:

Cheer up, face

The war is over!

Burma-Shave.

“By the start of the year,” Leonard Odell remembered, “we were getting the first repeat orders we’d ever had.” More signs went up, and within weeks, half the company stock sold out. Burma-Shave was in business.

Between 1926 and 1963, Burma Shave signs delighted drivers from coast-to-coast. The red and white signs were, Kiplinger’s wrote, “probably the most original advertising idea of all time.” Some Burma-Shave ads were simple pitches but most had a delightful tongue-in-cheek. To wit:

Before I tried it

The kisses

I missed

But afterward — Boy!

The misses I kissed.

Burma-Shave

AND

You know

Your onions

Lettuce suppose

This beets ‘em all

Don’t turnip your nose

Burma-Shave

From being just another shave cream, Burma-Shave became a national institution. As American as Route 66, Burma-Shave at its peak had 7,000 sets of signs in 45 states. Annual contests for best rhymes drew 50,000 entries. Many, Leonard Odell recalled, were “off-color. So, my dad would tell his secretary to compile the off-color ones and bring them home. And my mother and he would go into our library and close the door, and I’d hear all this uproarious laughter.”

Contest winners got $100 and the chance to see their doggerel on display.

If you think

She likes

Your bristles

Walk bare-footed

Through some thistles

Burma-Shave

During the Depression, as sales soared, Burma-Shave used its unique platform to promote safe driving. Some 40,000 drivers per year were killed, many either speeding or drunk. Burma-Shave’s cautions were hard to forget.

Speed

Was high

Weather was not

Tires were thin

X marks the spot

Burma-Shave

AND

Hardly a driver

Is now alive

Who passed

On hills

At 75

Burma-Shave

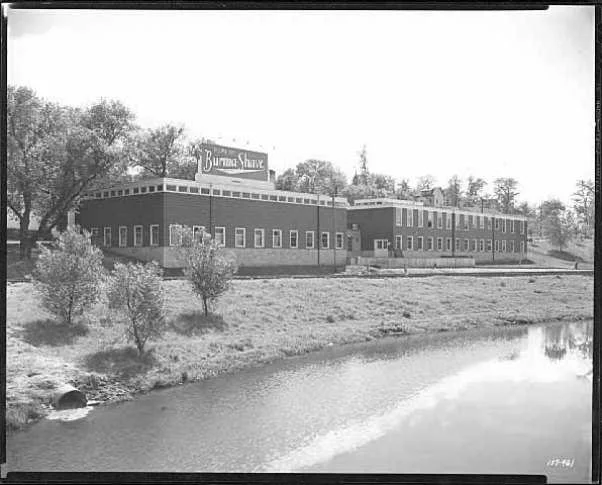

By 1940, Burma-Shave’s cream and signs were pouring out of a single factory in Minneapolis. Motoring families saw the signs coming, perked up, and paid attention right to the last line. A company “advance man” roamed the roads, searching for long stretches of highway where six signs, spaced three seconds apart at 35 mph, might fit.

Farmers freely donated land. “The farmers were kind of proud of those signs,” ad manager John Kamerer said. “They’d often write us if a sign had become damaged, asking us to ship a replacement that they’d put up themselves.”

During World War II, Burma-Shave joined the war effort.

Let's make Hitler

And Hirohito

Feel as bad

as Old Benito

Buy War Bonds

Burma-Shave

After the war, Burma-Shave poked fun at current concerns.

We don’t know

How to split an atom

But as for whiskers

Let us at’ em.

Burma-Shave

Despite steady sales, the company offered occasional promotions. A book of the 44 best verses, free with every jar! And then:

Free offer! Free offer!

Rip a fender off your car

Mail it in

For a half-pound jar

Burma-Shave

The Odells considered the fender deal a joke, but dozens of fenders, some from junkyards, some from toy cars, arrived in the mail. The family shipped free jars to every fender sender, even the pretenders. (Sorry, these jingles get in your head.)

One promotion, even more fantastical, inspired a devout fan.

Free – free

A trip to Mars

For 900

Empty jars

Burma-Shave

When posted in 1936, the pitch was laughed off. But when it was re-posted twenty years later, a Wisconsin man wired Burma-Shave saying his jar collection was nearing 900. When could he go to Mars? The Odells wired back:

If a trip to Mars

You earn

Remember, friend

There's no return.

But Arliss French was onto the game. He replied:

Let’s not Quibble

Let’s not Fret

Gather Your Forces

I’m All set.

To which Burma-Shave answered:

Our Rockets are Ready

We Ain’t Splitting Hairs

Just Send Us the Jars

And Arrange Your Affairs

When the Odells sent an advance man to Wisconsin, he found French in his grocery store promoting his trip. Outside was a model rocket and a sign: “Send Frenchy to Mars.” Locals were bringing in empty Burma-Shave jars. The number was nearing 900.

The executive offered to send French to the Mars Candy Company in Chicago. No deal. But after all 900 jars were trucked to Minneapolis, French and his wife accepted a trip to a small town in Germany. Moers (pronounced Mars).

By the late-1950s, Burma-Shave remained as clever as ever.

Dinah doesn’t

Treat him right

But if he’d

Shave

Dyna-mite!

Burma-Shave

But America was changing. Cars rarely tooled along at 35 mph, and the upstart interstate system had no room for Burma-Shave. In 1963, Philip Morris bought the company. Corporate lawyers, worried about lawsuits if some speeder crashed while reading signs, had them removed. The last one read:

Our fortune

Is your

Shaven face

It's our best

Advertising space

Burma-Shave

Beyond a few museums, no one knows what happened to the tens of thousands of red-and-white signs that once graced America’s roadways. A few are on e-bay, and if you slow down on old Route 66 outside Kingman, AZ or on Highway 30 near Ogden, Iowa, you can spot a few restored relics. But the rhymes, and the reason, have run their course. Let Burma-Shave have the last word.