THE MONUMENT TO HOPE

DECORATION DAY, 1897 — BOSTON — Amidst stars and stripes and brass bands, hundreds gather before the Massachusetts State House. The building’s gold dome gleams in the sun. Veterans in Union blue stand in formation. At noon, a canvas tarp is lifted from a single statue.

The crowd, accustomed to statues of lone men, white men, falls silent. For this memorial depicts not just another hero on horseback but also his troops. The mounted man is white. The troops are black.

“This monument tells a story like no other,” said historian David Blight. “It says African-Americans had to die to be counted as people. And from that, maybe, just maybe, the American Republic could be re-invented, re-imagined, remade, and maybe, still preserved.”

The “story like no other” blends white with black, a philosopher with a sculptor. It also pits democracy against its enemies, past and present. The story begins with emancipation.

Weeks after Lincoln’s proclamation, Massachusetts’ governor convinced the Secretary of War to recruit black troops. By February 1863, the Massachusetts 54th was training outside Boston.

“For a large party of us,” philosopher William James told the crowd on Decoration Day, “this was still exclusively a white man's war; and should colored troops be tried and not succeed, confusion would grow worse.”

But as eulogized in the best of all Civil War films, “Glory,” the “colored troops” astonished Americans. The astonishment debuted in Boston when the Mass 54th paraded past cheering crowds. Frederick Douglass shook the hand of each soldier (including his two sons). Then the astonishment moved toward battle behind a remarkable leader.

Robert Gould Shaw was the son of white privilege. A Harvard dropout, he enlisted, fought at Antietam, and was loyal to his own regiment. But Massachusetts’ governor needed someone to lead the 54th, a man “superior to a vulgar contempt for color, and having faith in the capacity of colored men for military service.”

At age 25, Shaw was chosen. Though reluctant, he honored his family’s abolitionist principles. Those principles were tested when his troops were given short pay. Shaw refused his own salary until his troops were paid in full. And after parading through Boston, Shaw and the 54th sailed to South Carolina.

The men were given menial work until Shaw convinced generals, skeptical of black courage, to let his soldiers fight. In mid-July 1863, they were sent on a suicide mission.

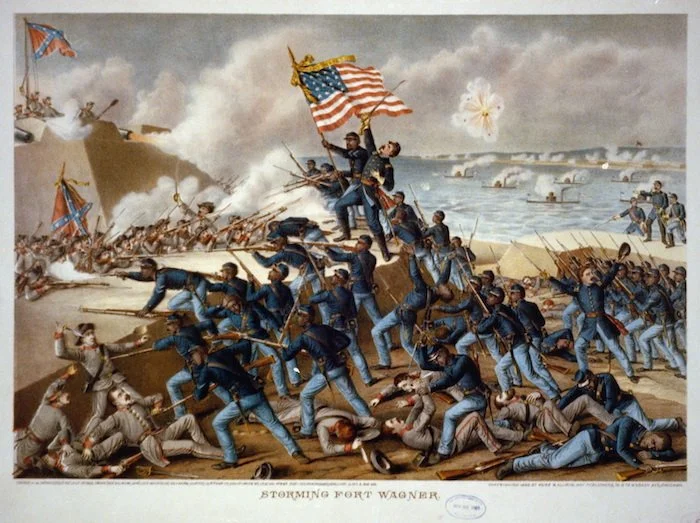

Fort Wagner stood guard over Charleston harbor. Surrounded by swamps and trenches, the fort held 14 cannons and rebels fixed for a fight. The first assault cost more than 300 Union lives. The next assault fell to the 54th.

At dusk, marching, then sprinting in a full frontal attack, the 54th was mowed down. Shaw was among the first to fall, shot through the heart. One of those watching was Harriet Tubman, “Moses” of the Underground Railroad, working as a Union cook.

“And then we saw the lightning,” Tubman recalled, “and that was the guns; and then we heard the thunder, and that was the big guns; and then we heard the rain falling, and that was the blood falling; and when we came to get in the crops, it was dead men that we reaped.”

Fort Wagner finally fell in September. By then, word of the 54th had spread, inspiring 180,000 black to enlist. Many say they tipped the balance of war.

A generation later, Fort Wagner was gone, washed into the sea. Shaw and 146 others were buried in a mass grave, unmarked. The Confederates who threw the white colonel atop black bodies considered it the final insult. Shaw’s family disagreed.

“We can imagine no holier place than that in which he lies, among his brave and devoted followers, nor wish for him better company. What a bodyguard he has!”

The Shaws and veterans of the 54th raised funds for a memorial at the site, but South Carolina objected. Boston did not. Sculptor August Saint-Gaudens began designing a memorial of Shaw alone on horseback. The Shaws would have none of that. His troops must be included. In an age of rank stereotypes, Saint-Gaudens hired black models and sculpted black faces.

On Decoration Day in 1897, after admiring a monument 14 years in the making, crowds moved to the Boston Music Hall. William James, whose younger brother was wounded at Fort Wagner, spoke.

“There they march, warm-blooded champions of a better day for man. There on horseback among them, in his very habit as he lived, sits the blue-eyed child of fortune, upon whose happy youth every divinity had smiled; Onward they move together. . .”

James then spoke about democracy itself, “still upon its trial.” Against all odds, American democracy had survived through “two inveterate habits carried into public life. . . One of them is the habit of trained and disciplined good temper towards the opposite party when it fairly wins its innings. It was by breaking away from this habit that the slave states nearly wrecked our nation. The other is that of fierce and merciless resentment toward every man or set of men who break the public peace. By holding to this habit the free states saved her life.”

Time has tarnished both democracy and the 54th memorial. In 2022, the restored monument was re-dedicated as a “beacon of hope.” But democracy remains on trial. And as we observe the re-named Memorial Day, this singular monument on the Boston Common suggests another call to courage, to citizenship.

Speaking at the re-dedication, scholar Ibram X. Kendi saw larger lessons. “This memorial is a testament to the fact that we did the impossible: abolished slavery. And it is also a testament to the fact that we can do the impossible again: abolish racism.”

And democracy?