THE REAL RHIANNON

With its power to get feet tapping and peel paint from walls, the banjo has a troubled but triumphant place in the American songbook. Bought to America by slaves strumming stringed gourds, the banjo became a crude joke at minstrel shows and a thrumming backup to Irish ballads. Finally, with a fifth string added, the banjo morphed into the dazzling showcase of bluegrass. By then, no black musician would touch a banjo. Enter Rhiannon Giddens, tuning up.

“The true story of the banjo,” she says, “is the true story of how America came together.” Rhiannon Giddens is a walking embodiment of American folk. Trained in opera, she brings audiences to their feet with gut-wrenching a capella ballads. Then she picks up a fiddle and rips into a hoedown. Next comes her own personal reincarnation of American banjo, a guttural music with more plunk than twang. And next?

“Few artists are so fearless and so ravenous in their exploration,” Pitchfork magazine wrote, while American Songwriter called Giddens “one of the most important musical minds currently walking the planet.”

Although she has won two Grammys in Folk, it’s hard to know what to call Giddens’ music. Folk seems too narrow. Jazz — occasionally. Blues — her soprano can certainly scrape your soul. Giddens just calls it “black, non-black music.”

Whatever you call it, Giddens pours both soul and heritage into every performance. Those performances began as a girl in Greensboro, North Carolina (above right) where she grew up “a nerd” who was constantly singing. Her choir teacher remembered, “I just thought, ‘There’s something about this child that is unique — her perception.’”

To set the “race record” straight, Giddens’ father is white, her mother black and part Native-American. (And although she is the right age to be named for the Fleetwood Mac song, she wasn’t. Her mother loved Welsh mythology.) Heritage made Giddens ever curious about her roots and the music that intertwined them.

“I hope that people just hear American music," she says of her work. "Blues, jazz, Cajun, country, gospel, and rock—it's all there. I like to be where it meets organically."

After studying opera at Oberlin College, Giddens was back in North Carolina, working as a singing hostess at The Macaroni Grill, when roots began rising. Believing that the banjo began with Earl Scruggs and ended with Bela Fleck, Giddens chanced upon a book about its history, black and white.

When she reached out to the author, she learned of an upcoming conference. At the “Black Banjo Then and Now Gathering” in Boone, NC, she met two like-minded musical scavengers. They soon formed a “post-modern string band” playing old black music long forgotten.

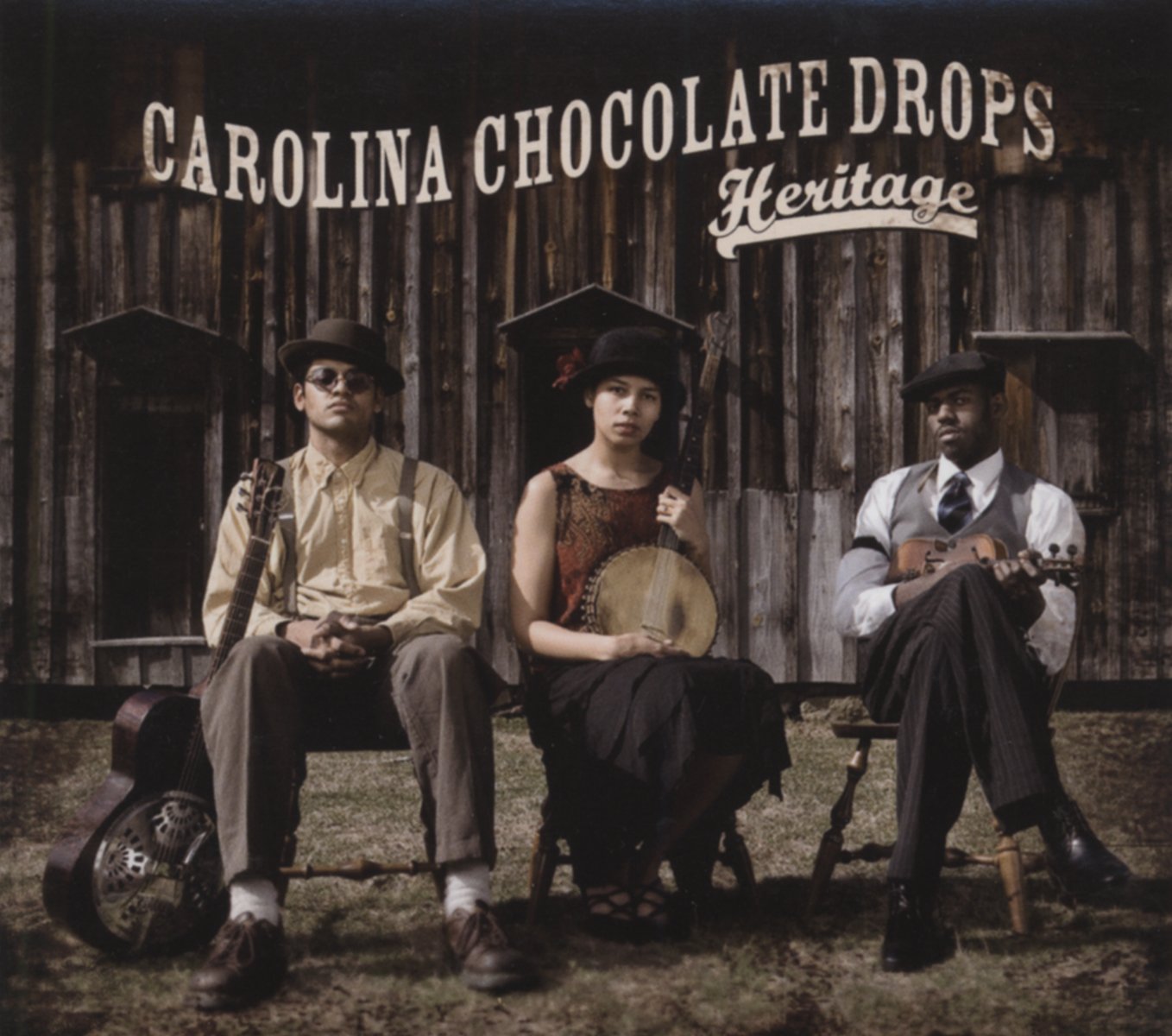

In 2006, “The Carolina Chocolate Drops” released their first album. With Giddens on banjo, fiddle, and vocals, Don Flemons on tenor banjo, bones, and jug, and Súle Greg Wilson on the Irish bodhrán, brushes, and washboard, the Chocolate Drops stepped from the 19th century straight into the 21st.

“It had been a long time since something so wonderfully disruptive had happened on the Southern folk scene,” John Jeremiah Sullivan wrote. “They shook things up by being black, of course, but more important, by reminding people that the music itself was black — as black as it had ever been white, anyway — and by owning it accordingly.”

For the next seven years, the Chocolate Drops played everywhere and everything. They surprised the Grand Ol’ Opry. They opened for Dylan. They did bluegrass and folk fests. They played old fiddle tunes, ragtime, ballads, blues, originals. Their second album, “Genuine Negro Jig,” won a Grammy in 2010.

But it’s always difficult to contain too much talent in one band. By 2013, the Chocolate Drops had gone separate ways. Giddens wasn’t sure which way she would go, but that fall she was invited to a concert celebrating the Coen Brothers’ Greenwich Village folk film “Inside Llewelyn Davis.”

The concert featured Joan Baez, Patti Smith, Jack White, and others. But Giddens, in a sleeveless scarlet dress, stunned the crowd with an a capella ballad, last heard from Odetta in the Sixties

There ain’t no hammer

That’s on a’-this mountain

That ring like mine, boy

That ring like mine.

The song ended in a silence that lasted several seconds. Then a burst of applause and a standing ovation. And Rhiannon Giddens was on her way to her first solo album. “It’s not about me, it’s about the music,” she told the New York Times. “My mom always said, you never do anything for money, power or prestige. I believe that. This is a calling, definitely.”

More Grammy nominations followed, then in 2017, a MacArthur genius grant. Studying and stretching her roots, she co-wrote an opera based on the story of the only Islamic slave in America. It won a Pulitzer. Then children's books — two based on her own songs. Then TV — she hosts PBS’ “My Music with Rhiannon Giddens” and she somehow found time to do a Great Books course on the history of the banjo.

This summer, Giddens will leave her home in Ireland to tour Europe, then play again at the Newport Folk Festival, along with several smaller concerts.

Her latest album, “You are the One,” is her first to feature all original compositions. These range from… oh, you get it by now — she’s all over the musical map. But it always comes back to the banjo.

Giddens favorite banjo surprises those who think they know the instrument. Fretless with strings of thick catgut, her banjo is “my axe.” And like an axe, it cuts through anything, especially tired stereotypes.

“Nobody owns an instrument,” Giddens says. “No culture gets to put the lockdown on anything.” That, she says, is the lesson taught by the banjo.

HEAR FIVE SONGS BY RHIANNON GIDDENS IN “I HEAR AMERICA SINGING”