A BICYCLE BUILT FOR HER

WICHITA, KS, 1896 — The news is shocking! Charles Dennison has filed for divorce. Seems a year back Charles gave his wife, Elma, a bicycle. Nothing has been the same since.

“Mr. Dennison says that his wife developed the bicycle fever to such a degree that she neglected everything — her home, her children, and her husband. She lived only for her wheel, and on it.” As proof that his wife has become a “bicycle fiend,” Mr. Dennison offers the following letter: “My Dear Husband — Meet me on the corner of Third Street and Seventh Avenue and bring with you my black bloomers, my oil can, and my bicycle wrench.”

Inventions that changed the world are few. Millennials talk of the smart phone, while Boomers recall the TV or PC. But in the 1890s, American life was shaken, startled, and shoved into a higher gear by a wonder we now take for granted — the bicycle.

“As a revolutionary force in the social world, the bicycle has had no equal in modern times,” Century Illustrated wrote in 1896. “What it is doing, in fact, is to put the human race on wheels for the first time in its history.”

Charming old ads and nostalgic tunes about a “bicycle built for two” romanticize the 1890s “bike boom.” But along with fun, the bike changed more than transportation. It gave women a rare taste of freedom. That taste, of course, did not come without a backlash.

For decades before 1890, bikes had been around the block, yet they were dangerous and decidedly for men only. It took macho daring to climb onto a “penny farthing” and ride six feet above the pavement pedaling a huge front wheel. Tires? Wooden or steel, earning these bikes the nickname “boneshakers.” Brakes? Sorry. Try back-pedaling.

Then a Parisian mechanic invented the “safety bike.” This precursor of today’s bikes had modest wheels, pedals, and a chain. The biggest innovation, however, was rubber tires. No more bone shaking.

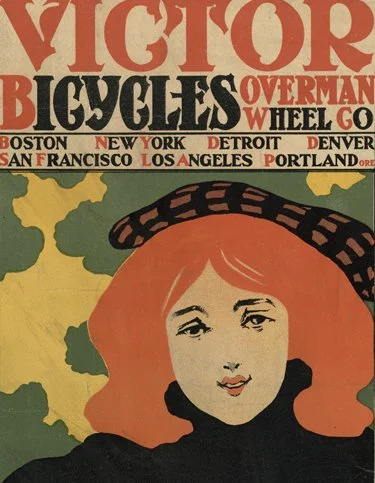

In 1887, the Overman Wheel Company in Chicopee Falls, MA began making the first American models. Come the new decade, the craze was on. New York Journal: “Man, woman and child — the population of Christendom — is awheel. The church? It is forgotten. The Sabbath? A cycling day. The horse? Token and companion of gentlemanhood. Tobacco has been forsaken. Politics has become merely a catering to the wheelmen’s wishes.”

Everyone, it seemed, wanted a bicycle. And as prices dropped to under $100, as lighter bikes replaced 50-pound clunkers, everyone — every adult anyway — got one. Queen Victoria rode a bike. Tolstoy learned to ride — at his age! Wheel clubs sent hundreds of riders on evening jaunts, sometimes to the tune of brass bands. But the most revolutionary riders — one third of the total — were women.

“Does the New Woman spring from the bicyclist,” the Chicago Tribune asked, “or does the bicyclist spring from the New Woman? They are certainly cousins.” The basic build of the bicycle, however, posed a basic problem for Victorian America.

Women could ride horseback — sidesaddle. But riding a bike required straddling the seat. In a long skirt? With petticoats? “Some friends and I were riding one day against a very heavy wind,” one woman wrote, “when it caught my skirt and wound it around my pedal, throwing me. The rapid gait I was going caused the force of the fall to break my arm. It laid me up six weeks.”

The answer was a garment decades old but shunned by (ahem!) proper women. Suffragette Amelia Bloomer might wear these baggy pantaloons, but no self-respecting woman would. Until bicycles came along.

As sales of bikes and bloomers soared, women rode free! Free from husbands, housework, drudgery. It was wonderful, so wonderful that it had to be stopped. Nebraska’s Women’s Rescue League complained that bicycles led women “headlong into the devil.” Congress should pass a law! More than one divorce was blamed on a wife who “spent nearly all her time riding on her wheel.” Yet women fought back.

Bloomers and bikes, one wrote, simply show “that women have legs like any one else, and that they are made for use.” The bicycle, she added, “marks the beginning of a new era.”

In 1896, Margaret DeLong biked from Chicago to San Francisco — alone (carrying a pistol). But further jeremiads followed: “Have we not sexual troubles enough on our hands without opening Pandora’s Box and hauling out a bike?”

Still the craze continued. Back in 1890, America had 80,000 bikes. Six years later, the number topped a million, “Everything is bicycle,” author Stephen Crane noted. As bicycles bloomed, business suffered. Cigar makers, saloons, shoe salesmen, all saw sales slump. “There is nothing in my business any longer,” a Manhattan barber complained. “The bicycle has ruined it.”

The boom finally went bust as a new century approached. Someone figured out how to motorize a bicycle, making 10 m.p.h. seem slow. Automobiles were in the making. Bike companies, having overproduced, went bankrupt, but the legacy lived on.

No, bicycles did not “lead to sterility in the male.” They did not give women “bicycle face,” nor did they “annihilate the reading habit.” (Blame TV and smart phones for that.) But having opened a new world for “bicycle girls,” the simple two-wheeler sowed seeds of liberation.

Said suffragette Susan B. Anthony, “The bicycle has done more for the emancipation of women than anything else in the world.” Ride on!